Tenochtitlán: The Fascinating Ancient City Under Mexico City

Updated On: April 20, 2024 by Courtney Augello

Deep within the bustling heart of modern-day Mexico City lies the remnants of an ancient marvel—Tenochtitlán, the capital of the mighty Aztec Empire. This city draws in tourists from around the world to embark on a journey through time and culture.

To help you explore and admire the history that thrives in Tenochtitlán, we’ve explored the history, culture, and historical attractions that make the ancient city come alive as a thriving tourist destination.

Table of Contents

What is Tenochtitlán?

Tenochtitlán, often described as the jewel of the Aztec Empire, was an awe-inspiring city. Its origins date back to the early 14th century when the wandering Mexica people, led by their legendary chieftain Tenoch, arrived in the Valley of Mexico.

The Mexica were a Nahuatl-speaking tribe originally hailing from the semi-mythical city of Aztlan. Legend has it that their deity, Huitzilopochtli, guided them to their destined homeland by sending a divine sign—a majestic eagle perched on a cactus while clutching a serpent in its beak.

This sign was prophesied to represent where they should establish their capital, so they founded Tenochtitlán on the swampy, marshy islands of Lake Texcoco around 1325 AD. This strategic location provided a natural defensive barrier against enemies and access to aquatic resources.

Characteristics

Tenochtitlán was more than just a city. It was a testament to the architectural and engineering prowess of the Aztec civilisation. Its urban layout featured a grid-like system of streets and canals, allowing efficient transportation and trade.

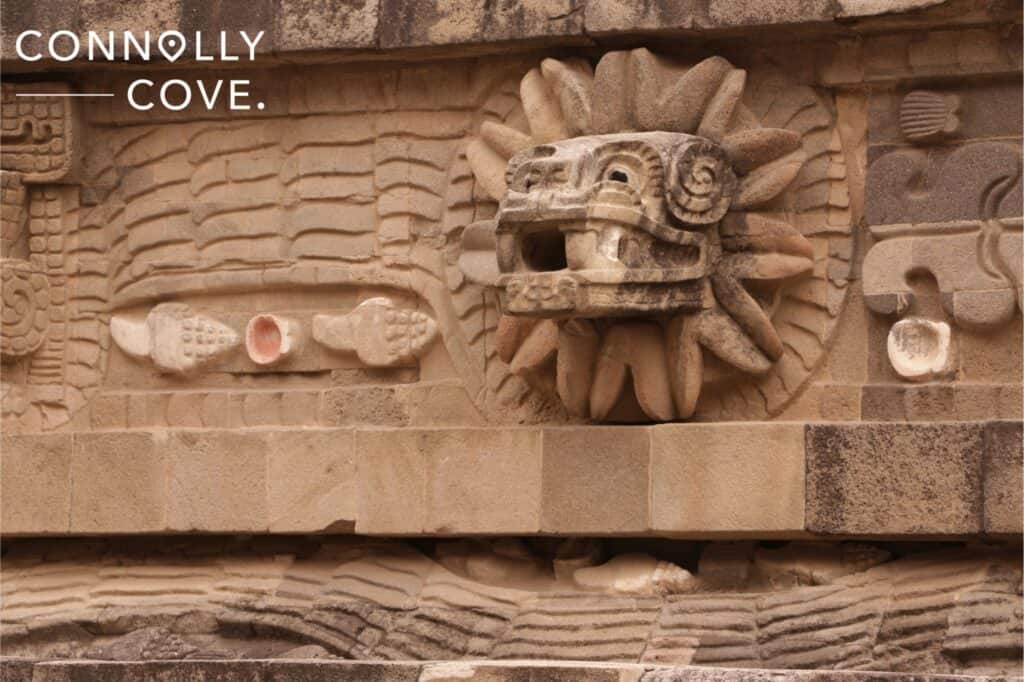

At its heart stood the Templo Mayor, an imposing pyramid-like structure dedicated to the dual gods of Huitzilopochtli, the god of war, and Tlaloc, the god of rain. The temple was adorned with intricate carvings and sculptures, showcasing the Aztecs’ artistic skill and religious devotion.

Tenochtitlán was also a vibrant cultural hub. The Aztecs were known for their rich mythology, complex religious rituals, and distinctive art. The city was filled with markets where traders from across the empire gathered to exchange goods such as precious metals, textiles, and exotic foods.

Economic and Political Importance

Tenochtitlán’s economic significance was boosted by its strategic location. The city’s position on Lake Texcoco allowed effective control of the region’s trade routes and agricultural resources.

The chinampas, artificial agricultural islands created by the Aztecs, provided fertile grounds for farming crops, sustaining a burgeoning population. The Aztecs also harvested resources from the lake, such as fish and plants, further contributing to their prosperity.

Politically, Tenochtitlán was the capital of the Aztec Empire, a dominant force in Mesoamerica during the 15th and early 16th centuries. Under rulers like Moctezuma II, the Aztecs expanded their influence through military conquest and a system of tributary states, amassing vast wealth and power.

Tenochtitlán served as the epicentre of the empire, hosting administrative centres, tribute collection points, and elite residences. Its political importance extended beyond its borders as it established alliances and trade relationships with neighbouring city-states.

Where is Tenochtitlán?

Tenochtitlán, the ancient capital of the Aztec Empire, was strategically located in the Valley of Mexico, in what is now the heart of modern-day Mexico City. The city was situated on a group of islands in the middle of Lake Texcoco, a vast and shallow lake surrounded by mountains and volcanoes.

The closest major cities to Tenochtitlán in the Valley of Mexico included Tlatelolco, which was located on an adjacent island and served as a twin city to Tenochtitlán, as well as Texcoco and Tacuba, which were situated on the mainland.

Today, tourists interested in exploring the historical and cultural remnants of Tenochtitlán can visit Mexico City, the bustling capital of Mexico. Mexico City is well-connected to the rest of the world by air travel, with Benito Juárez International Airport as the primary gateway.

Features of the Region

The Valley of Mexico, where Tenochtitlán was built, has a unique and diverse topography. The valley is nestled among the Sierra Madre Oriental and Occidental mountain ranges, which provided natural protection and isolation for the city.

One of the most striking features of the region was the chinampas, artificial islands created by the Aztecs for agricultural purposes. These rectangular plots of land were constructed by dredging nutrient-rich mud from the lake bottom and building up layers of soil and vegetation.

The volcanic landscape surrounding the Valley of Mexico also added to its uniqueness. Several prominent volcanoes, including Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl, are visible from the valley and hold significant cultural and mythological importance in Aztec cosmology.

Climate and Environment

The climate of the Valley of Mexico is characterised by its high altitude and temperate climate. Located at an elevation of approximately 2,240 meters (7,350 feet) above sea level, the valley enjoys mild temperatures year-round.

However, the region experiences distinct wet and dry seasons due to its high altitude. The rainy season typically occurs from May to October, while the dry season spans from November to April.

The valley’s climate provided favourable conditions for agriculture. It allowed for the cultivation of various crops, including maise, beans, and squash, which formed the basis of the Aztec diet.

The History of Tenochtitlán

The history of Tenochtitlán is intimately intertwined with the rise of the Aztec civilisation. The Aztecs, also known as the Mexica, originated from the region of Aztlan, a mythical ancestral homeland.

While the exact location of Aztlan remains a subject of debate among scholars, it is widely believed to have been situated in northern Mexico. The Mexica were part of a larger group of Nahuatl-speaking tribes who migrated southward in search of a new homeland.

This migration, which likely occurred in the 12th or early 13th century, was a pivotal moment in the history of the Aztec civilisation. The Mexica, under the leadership of their chieftain Tenoch, embarked on a journey guided by their patron deity, Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun.

According to Aztec mythology, Huitzilopochtli appeared to Tenoch in the form of an eagle perched on a cactus, devouring a serpent. This sacred sign marked the spot where they were to establish their capital.

Foundation of Tenochtitlán

In 1325 AD, the Mexica reached the Valley of Mexico, a fertile basin surrounded by mountains and volcanoes settled on a group of marshy islands in the middle of Lake Texcoco. Here, they founded their capital, Tenochtitlán, which would go on to become one of the most powerful and sophisticated cities in the Americas.

The founding of Tenochtitlán marked the beginning of a new era for the Mexica. They built their city with remarkable ingenuity, constructing artificial islands, creating causeways to connect them, and erecting monumental structures.

Tenochtitlán rapidly grew in size and influence, eventually becoming the capital of the Aztec Empire, which dominated much of Mesoamerica through a combination of military prowess and diplomatic alliances.

In the centuries that followed, Tenochtitlán’s history would be marked by expansion, cultural flourishing, and, ultimately, the arrival of Spanish conquistadors led by Hernán Cortés in 1519.

The encounter between the Aztec civilisation and the Spanish expedition would lead to profound and irrevocable changes in the history of Tenochtitlán and the Americas as a whole.

Growth and Expansion

The growth and development of Tenochtitlán were closely linked to the remarkable expansion of the Aztec Empire. Under the leadership of rulers like Moctezuma I and Ahuitzotl, the Aztecs embarked on a series of military campaigns in the 15th century, which led to the subjugation of neighbouring city-states and regions.

The Aztec Empire gradually extended its influence across central Mexico, encompassing a vast territory that included present-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and parts of Honduras and El Salvador.

The expansion of the empire brought considerable wealth to Tenochtitlán. Tribute payments flowed into the city from the conquered regions, including valuable goods such as gold, silver, textiles, exotic animals, and agricultural products.

This wealth fueled the city’s growth and allowed for the construction of elaborate temples, palaces, and infrastructure projects. The Aztecs established a tributary system that consolidated their power and maintained a delicate balance of alliances with the conquered states.

Urban Planning and Architecture

Tenochtitlán was renowned for its urban planning and architectural marvels, which reflected the sophistication of the civilisation. The city’s layout was a testament to meticulous planning, featuring a grid-like system of streets and canals crisscrossing the manmade islands.

The canals served as both transportation routes and drainage channels, effectively managing the challenges of the city’s swampy terrain. Causeways and bridges connected the city to neighbouring settlements, facilitating trade and communication.

Tenochtitlán featured a range of facilities, including public baths, ball courts for traditional Mesoamerican games, and botanical gardens where exotic plants were cultivated. The city’s infrastructure also included an advanced water supply system, with aqueducts and reservoirs designed to meet the needs of its burgeoning population.

Spanish Conquest

The arrival of Hernán Cortés and his expedition in 1519 marked a turning point in the history of Tenochtitlán and the Aztec Empire. Cortés, a Spanish conquistador, arrived on the Gulf Coast of Mexico with the ambition to explore and conquer the lands rumoured to exist beyond the coast.

Cortés’s expedition, comprised of a relatively small force of Spanish soldiers, was driven by a combination of factors, including a desire for wealth and glory, religious zeal, and the prospect of expanding Spanish influence in the New World.

As he advanced inland, Cortés formed alliances with some indigenous groups who were eager to challenge the dominance of the Aztecs. These alliances gave him valuable intelligence about the Aztec Empire, its political structure, and its vulnerabilities.

Siege of Tenochtitlán

The climax of the Spanish conquest of Tenochtitlán came in 1521 when Cortés laid siege to the city. The siege was gruelling, marked by fierce battles, hunger, and disease. The Spanish forces faced significant challenges, including the Aztecs’ resilient defence and the city’s narrow causeway.

Despite these obstacles, the siege eventually took its toll on the Aztec defenders. The city’s population suffered from food shortages and devastating epidemics of smallpox, which had been inadvertently introduced by the Spanish.

The final blow came when the Spanish breached the city’s walls and, with the assistance of indigenous allies, overran Tenochtitlán’s defences. The consequences of the fall of Tenochtitlán were profound and far-reaching. It marked the end of the Aztec Empire and the beginning of Spanish colonial rule in Mexico.

The conquistadors looted the city of its treasures, dismantled its temples, and sought to impose Christianity upon the indigenous population. The once-mighty city of Tenochtitlán was razed to the ground, and its grandeur was replaced by Spanish colonial architecture and institutions.

The Spanish conquest also had a devastating impact on the indigenous population. The introduction of European diseases, forced labour, and religious conversion significantly reduced the indigenous population.

Modern Exploration and Excavation

Archaeological discoveries

Modern exploration and excavation have unveiled the secrets of Tenochtitlán, providing invaluable insights into the Aztec civilisation and the city’s history. Archaeological efforts have revealed the buried remnants of this once-great city, buried beneath the busy streets of modern Mexico City.

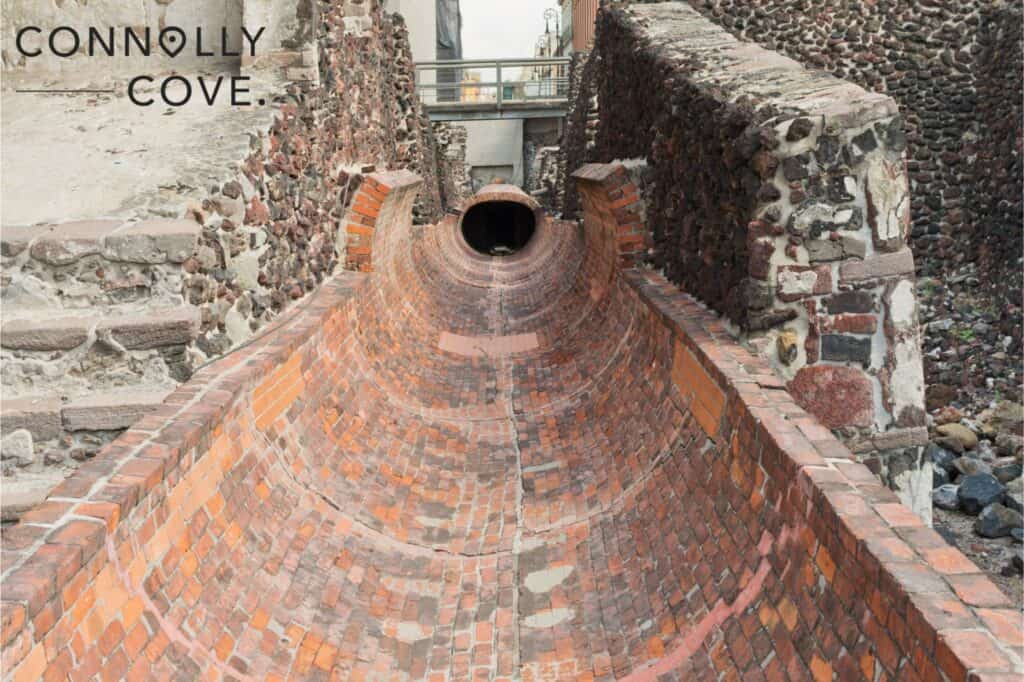

Excavations have uncovered the foundations of temples, pyramids, marketplaces, and residential areas, shedding light on the city’s layout, architecture, and daily life.

One of the most significant discoveries was the Templo Mayor, the grand pyramid-like temple dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc. The excavation of this sacred site unearthed a treasure trove of artefacts, including sculptures, offerings, ritual objects, and the remains of Aztec rulers and sacrificial victims.

Preservation Efforts

Preserving the archaeological treasures of Tenochtitlán has become a paramount concern. Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) has spearheaded efforts to safeguard and conserve the city’s ruins.

Conservationists have employed various techniques, including stabilisation of structures, protection from environmental factors, and restoration of key monuments. One notable preservation effort is the Templo Mayor Project, an ongoing initiative that aims to restore and protect the Templo Mayor complex.

Efforts have also been made to address Mexico City’s subsidence. The city is gradually sinking due to its location on a former lakebed, threatening the stability of Tenochtitlán’s ruins. Engineers and conservationists are working to address these subsidence issues to protect the city’s archaeological heritage.

Museums and Exhibitions

Museums and exhibitions provide a platform for sharing Tenochtitlán’s history and culture with the public. The National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City houses many artefacts from Tenochtitlán and the Aztec Empire.

Visitors can explore intricately carved stone monuments, colourful featherwork, and other relics that showcase the city’s artistic and cultural achievements. Furthermore, Tenochtitlán’s legacy is celebrated through exhibitions and cultural events within Mexico and around the world.

Temporary exhibitions often feature artefacts and discoveries related to the city, allowing visitors to engage with its history and significance. These exhibitions educate the public and promote a deeper appreciation of the Aztec civilisation’s contributions to human heritage.

Things to Do at Tenochtitlán

Visit the Templo Mayor

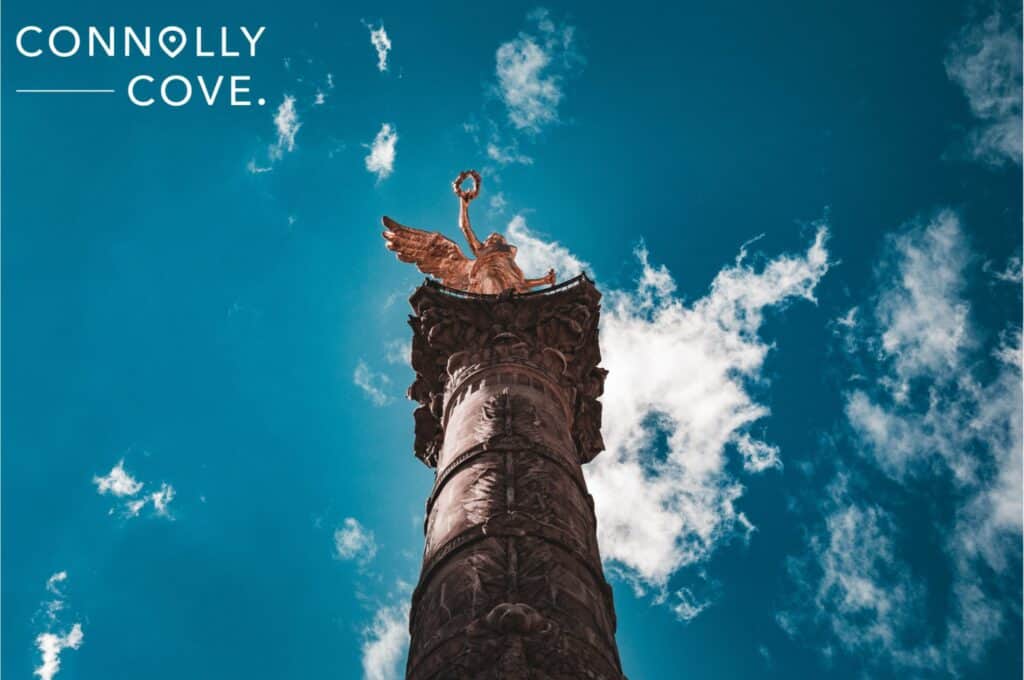

A visit to Tenochtitlán would be incomplete without exploring the Templo Mayor, the city’s most iconic and spiritually significant structure. The Templo Mayor, or “Great Temple,” served as the epicentre of Aztec religious life and was dedicated to two principal deities: Huitzilopochtli, the god of war and the sun, and Tlaloc, the god of rain and fertility.

The Templo Mayor had a profound connection to the Aztec creation myth, as it was believed to be the very spot where the god Huitzilopochtli had guided the Mexica people to establish their capital.

This divine mandate made the temple a sacred place where offerings and sacrifices were made to ensure the sun’s daily rise, the arrival of life-giving rain, and the prosperity of the Aztec Empire. Its history is deeply intertwined with the spiritual beliefs and practices of the Aztec civilisation.

For tourists visiting Tenochtitlán, a journey to the top of the Great Pyramid is a must for a breathtaking experience. This awe-inspiring pyramid offers visitors a chance to ascend its stone steps and gain panoramic views of the ancient city’s ruins and the surrounding metropolis of Mexico City.

Reaching the summit of the Great Pyramid provides an extraordinary vantage point to appreciate the city’s layout and architecture. From this elevated perspective, you can observe the remnants of the city’s grid-like streets and the surrounding mountains.

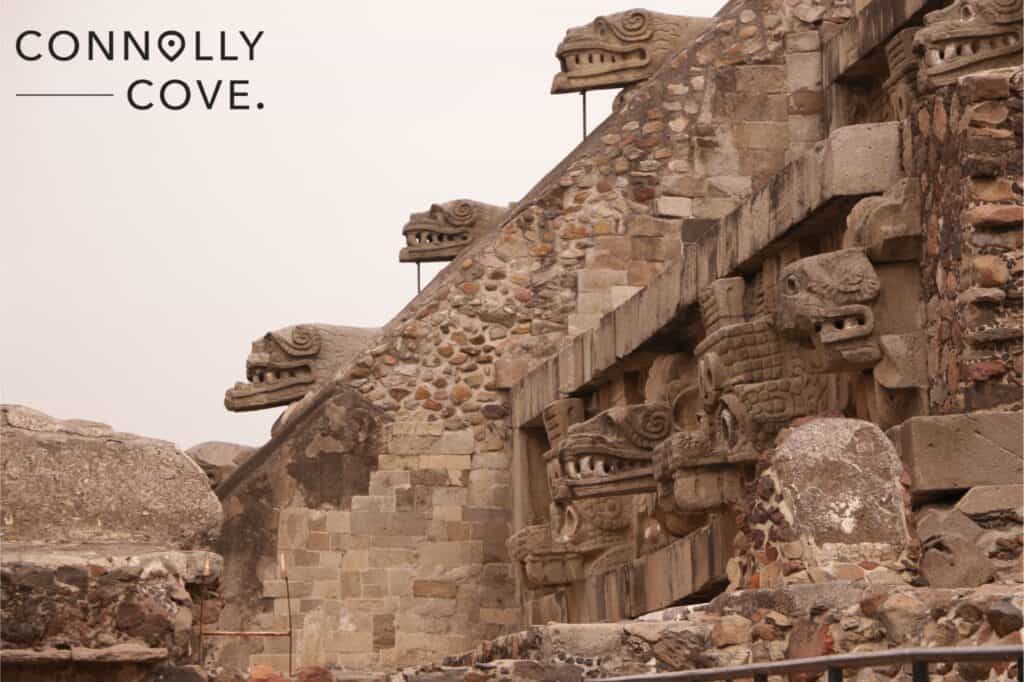

Architectural Features

The Templo Mayor’s architectural features reflect the grandeur and complexity of Aztec religious structures. The temple consisted of a dual pyramid complex, with two separate shrines dedicated to Huitzilopochtli and Tlaloc, each accessible by a steep staircase.

One striking aspect of the temple’s architecture was its use of massive stone blocks and intricate carvings. The stone facades were adorned with sculptures of deities, mythological creatures, and intricate patterns that showcased the artistic skills of the Aztecs.

Visitors to the Templo Mayor can witness ongoing archaeological excavations and marvel at the architectural elements that have been uncovered. The site offers a glimpse into the monumental efforts required to construct and maintain such a sacred edifice.

Stroll the Streets of Tenochtitlán

Tourists visiting Tenochtitlán can embark on a fascinating journey by strolling through the reconstructed ancient streets of this once-great city. While most of Tenochtitlán’s structures were lost to time and the Spanish conquest, efforts have been made to reconstruct and preserve key elements of the city’s layout.

One of the most remarkable features of Tenochtitlán’s streets is their grid-like layout. The city’s urban planning was an example of advanced engineering and organisation, with well-designed streets intersecting at right angles.

Tourists can walk along these streets and marvel at the precision and symmetry of the city’s layout. The experience of wandering through the reconstructed streets provides a tangible and immersive experience of the city’s past and the world of the Aztecs.

Insights into Daily Life

Strolling through the ancient streets of Tenochtitlán offers tourists unique insights into the daily life of its inhabitants. Along these streets, vendors once plied their trade in bustling markets, and residents went about their daily routines. Visitors can envision the Aztec life, from merchants selling exotic goods to families doing their daily chores.

The streets also reveal remnants of residential areas, showcasing Aztec homes’ architectural style and organisation. These provide a deeper understanding of the social dynamics, economy, and culture of Tenochtitlán. The city was not just a religious and political centre but also a thriving place where people lived, worked, and socialised.

Visit the Museum of Anthropology

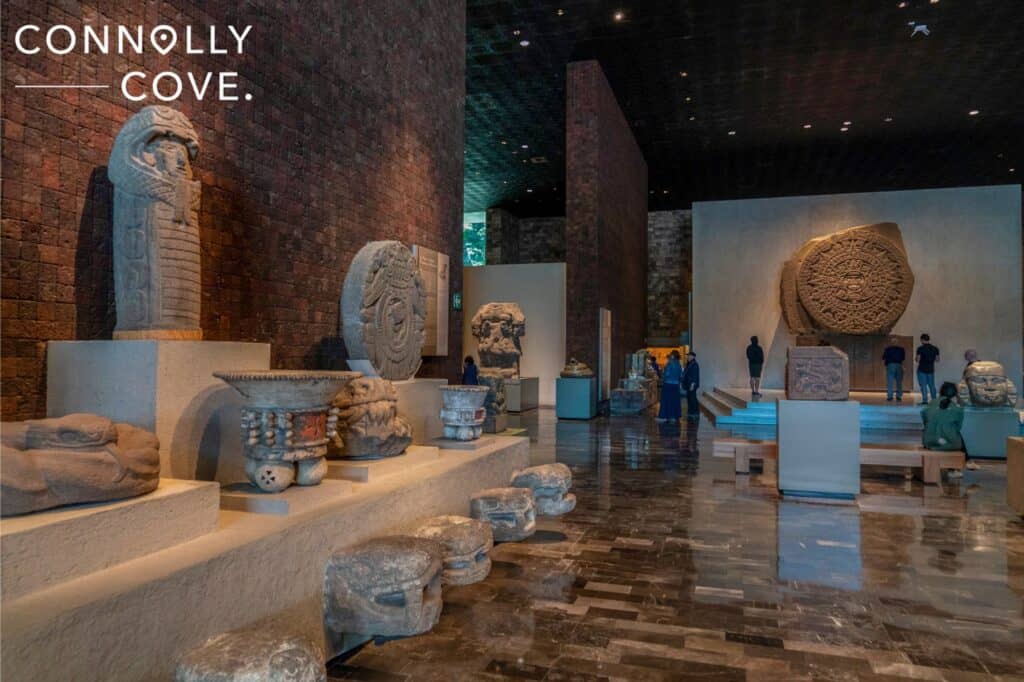

A visit to the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City is a remarkable opportunity for tourists to delve deeper into the history and culture of Tenochtitlán. The museum boasts an extensive collection of exhibits that shed light on the city’s significance in the Aztec civilisation and its enduring legacy.

The galleries dedicated to Tenochtitlán provide a comprehensive overview of the exotic city’s history, society, and artistic achievements. Visitors can explore exhibits that feature detailed models and recreations of Tenochtitlán, allowing them to explore the city’s layout, architecture, and urban planning.

Interactive displays provide insights into Aztec daily life, from agricultural practices on chinampas to the vibrant marketplaces where goods from across the empire were traded. The museum’s exhibits also delve into the religious significance of the Templo Mayor, with artefacts and displays illustrating the rituals and ceremonies held there.

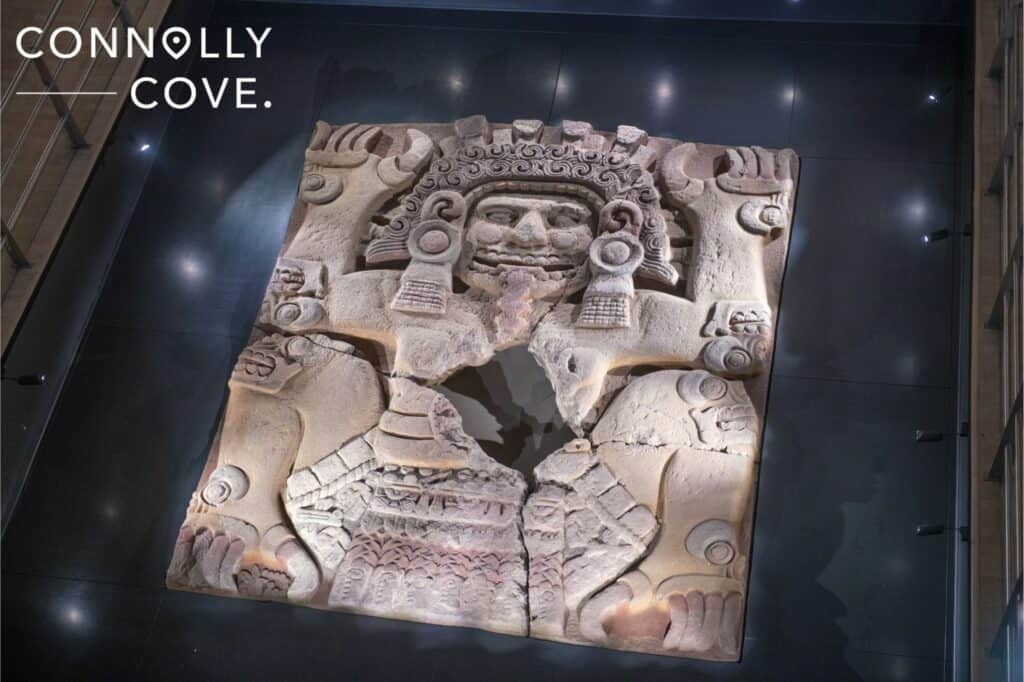

Artefacts

The Museum of Anthropology houses an extensive collection of artefacts related to Tenochtitlán, including intricate stone carvings, sculptures of deities, ceramics, jewellery, paintings, feathered headdresses, and textiles. Each artefact tells a story about the Aztec civilisation, its artistic achievements, and its spiritual beliefs.

One of the most significant artefacts on display is the Aztec Calendar Stone, also known as the Sun Stone. This colossal stone disc, intricately carved with symbols and imagery, represents the Aztec cosmos and the passage of time. It serves as a symbol of the Aztec’s profound understanding of astronomy and their connection to the natural world.

Featherwork, another highlight of the museum’s collection, showcases the artistic excellence of the Aztecs. These elaborate pieces, made from the feathers of exotic birds, were used in religious ceremonies and as status symbols. The craftsmanship and vibrant colours of featherwork artefacts provide a vivid glimpse into Aztec aesthetics.

Experience Aztec Cuisine and Culture

One of the delightful ways for tourists to immerse themselves in the Aztec culture of Tenochtitlán is by savouring traditional cuisine at local restaurants. Mexico City offers a plethora of dining establishments that serve dishes inspired by the rich culinary traditions of the Aztecs and their predecessors.

Mole, a complex sauce made with ingredients such as chillies, chocolate, and spices, is a staple of Aztec cuisine and can be found on many restaurant menus. Tourists can also try dishes made with native ingredients like amaranth, chia seeds, and cactus.

Exploring the local food scene allows tourists to connect with the flavours of the Aztec civilisation and appreciate the culinary diversity that has evolved over the centuries. It’s a delicious way to experience the cultural heritage of Tenochtitlán.

Events and Festivals

Tourists seeking a deeper cultural immersion can time their visit to coincide with local events and festivals celebrating the Aztec heritage of Tenochtitlán. Mexico City hosts various cultural events throughout the year, many of which pay tribute to the city’s ancient past.

One event is the Festival del Centro Histórico, which features music, dance, theatre performances, and art exhibitions inspired by the Aztec and Mesoamerican traditions. Visitors can admire colourful processions and traditional dances that reflect the city’s vibrant past.

Additionally, tourists can participate in the Day of the Dead (Día de los Muertos) celebrations, a deeply rooted Mexican tradition that blends indigenous and Catholic beliefs. During this festival, altars are adorned with offerings of food and marigold flowers, and the streets come alive with parades and vibrant decorations.

These cultural events and festivals provide tourists with a firsthand experience of the living traditions passed down through generations since the time of Tenochtitlán. It’s a chance to witness the continued vibrancy of Aztec culture and its enduring influence on modern Mexican life.

Tenochtitlán is a Fascinating Ruin to Explore

Tenochtitlán, the once-mighty capital of the Aztec Empire, is a testament to the rich history, culture, and significance that defines its legacy. From its humble beginnings as a nomadic tribe’s vision to its rise as a grand metropolis, Tenochtitlán’s history is a captivating tale of ambition, innovation, and resilience.

Tenochtitlán draws tourists to go on a captivating journey through time that bridges the gap between ancient civilisations and contemporary Mexico. Tenochtitlán transports visitors into the heart of a civilisation that thrived centuries ago and left an undeniable mark on the history and heritage of Mexico.

If you’re interested in exploring more fascinating destinations, check out our blog on Unearthing the World’s Most Splendid Hidden Gem Destinations.