Explore The Great Valley of The Kings

Updated On: November 10, 2023 by Marise

The Valley of the Kings was a tourist attraction in antiquity, particularly during the Roman times, and is considered one of the greatest sites of Egyptology-related archaeological expeditions over the past two centuries.

Located on the western bank of the majestic Nile River near Luxor, the Valley of the Kings in Egypt is a timeless repository of awe-inspiring history, grandeur, and intrigue. This archaeological treasure trove, a final resting place for numerous pharaohs, has captivated the world for centuries.

Beyond its fascinating excavation history, which has revealed a wealth of knowledge about ancient Egyptian civilization, the Valley of the Kings continues flourishing as a vibrant centre for modern-day tourism.

This blog embarks on a journey through this renowned site, tracing its excavation history and exploring the contemporary attractions that make it a popular destination for tourists from around the world. Scroll to read through the history, or click on one of the headings below to jump to a specific section.

Table of Contents

What is the Valley of the Kings?

The Valley of the Kings, located on the western bank of the Nile River near Luxor in Egypt, is an ancient burial ground that holds a prominent place in Egyptian history. It is a site of immense archaeological and historical significance, known for being the final resting place of numerous pharaohs, nobles, and high-ranking officials of the New Kingdom period of ancient Egypt.

The valley, referred to as the “Great and Majestic Necropolis of the Millions of Years of the Pharaoh, Life, Strength, Health in the West of Thebes,” served as a burial ground from around the 16th to the 11th century BCE, during the New Kingdom period of Egypt.

The Valley of the Kings gained worldwide recognition primarily for its intricate and well-preserved tombs, which were ingeniously designed to protect the deceased and their treasures. These burial chambers, concealed within the arid cliffs of the valley, were carved into the rock, providing a concealed and fortified location for the burial of pharaohs.

The most famous among these tombs is that of Tutankhamun, whose tomb was discovered by British archaeologist Howard Carter in 1922. The treasures found within Tutankhamun’s tomb, including his iconic golden mask, have captivated the world and provided invaluable insights into ancient Egyptian culture and funerary practices.

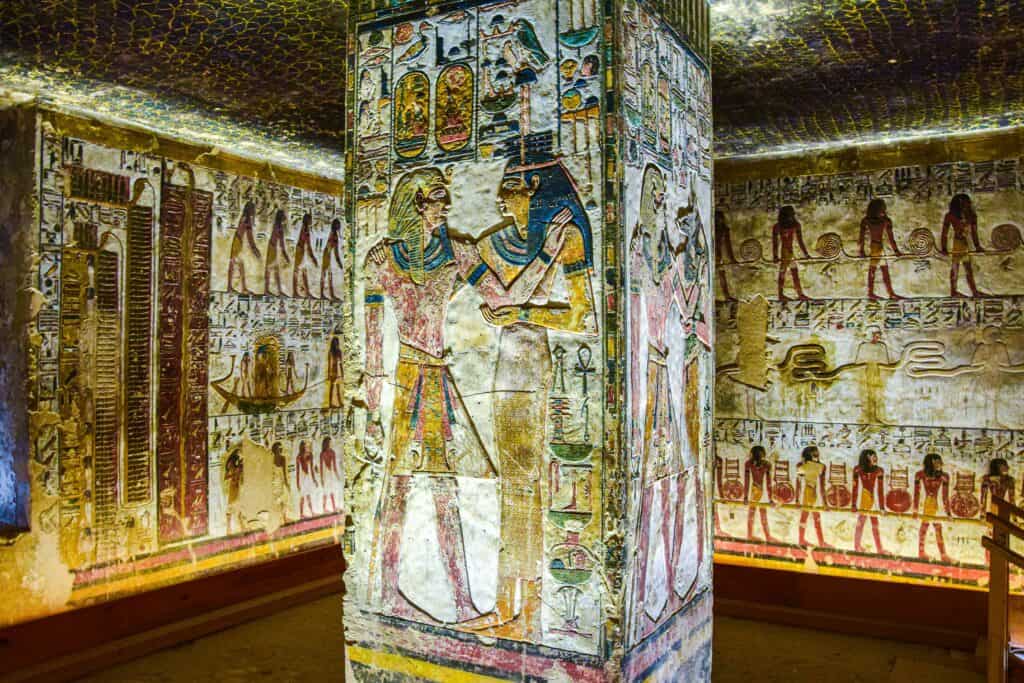

Beyond the remarkable discoveries, the Valley of the Kings is a testament to the ancient Egyptian belief in the afterlife and their meticulous preparation for it. The intricate artwork and inscriptions within the tombs depict scenes from Egyptian mythology and rituals designed to help the pharaohs navigate the challenges of the afterlife.

The walls are adorned with depictions of gods, magical spells, and prayers meant to ensure the deceased’s safe passage into the eternal realm. These vivid murals and hieroglyphs offer a profound glimpse into the religious and spiritual beliefs of ancient Egypt.

The meticulous craftsmanship, rich symbolism, and invaluable archaeological discoveries within this sacred valley have contributed immeasurably to our understanding of Egyptian history and culture. The legacy of the Valley of the Kings endures as an enduring link to the past, allowing us to connect with the pharaohs and their quest for immortality.

Exploration of the Valley of the Kings Throughout History

Everything in the Valley of the Kings has been thoroughly documented, from the theft of antiquities and the looting of tombs to the scientific studies that uncovered the entire burial city of Thebes. Despite these expeditions, not all details of the 11 tombs are known. There is ample evidence of scientific attempts to study the area over the centuries.

The Greek philosophers Strabo (1st century B.C.) and Diodorus (1st century A.D.) studied the number of tombs in Thebes and estimated there to be around 47. They were shockingly correct in their estimate but, unfortunately, learned that the rest of the tombs had been destroyed.

Even the famous Greek geographer Pausanias (2nd century AD) made numerous observations on the Valley of the Kings and its “pipe pass”, describing the descent to the entrance of the tomb.

In addition to the scholars and writers who come to the area, many tourists visit the Valley. This explains why there are many inscriptions written in languages that people did not use when the tombs were excavated.

The inscriptions throughout the Valley of the Kings are written in Phoenician, Coptic, and many other languages. Most of these inscriptions were found in Tomb 9, which contains about a thousand inscriptions. The oldest recorded inscription dates back to 278 BC.

Before The 19th Century

Before the 19th century, exploring the Valley of the Kings was challenging and expensive. The city of Thebes has yet to be discovered. All available information about this city referred to its location on the banks of the Nile.

Thebes had always been confused with Memphis, the capital of Egypt in the old kingdom, or any other city before the modern era. Danish artist Frederik Louis Norden first documented the sighting of tombs in Thebes. He was followed by King Richard Pocock of England, who published the first modern map of the Valley of the Kings in 1743.

1799

In 1799, scientists from a French expedition, including Dominique Vivan, made a detailed map of every tomb that had been discovered in the Valley of the Kings. Before they found the Valley, they first discovered an area to the west that also featured tombs.

The French researchers published 24 books detailing the history of Egypt. They also published two complete volumes in the “Explanation of Egypt” encyclopedia describing Thebes and its surroundings.

19th Century

As early as the turn of the nineteenth century, a series of European reconnaissance activities in the Valley of the Kings succeeded in deciphering the hieroglyphs of Champollion. The reconnaissance campaign began under Belzoni, commanded by Henry Salt.

They were able to find many tombs and graves during their expedition.

1816 and 1817

In 1816, the tomb of Khabar Khapro-Ra in the western valley (tomb 23) was discovered, and the tomb of Seti I (tomb 17) was found the following year. After a visit to the area, Belzoni reported the findings.

Due to the great value of the excavation, the Consul General of France, Bernardino Drovetti (Grime Belzoni and Salt), would have worked alone in the same research area.

1827

In 1827, John Gardner Wilkinson was commissioned to identify every tomb place in the Valley. His goal was to create a collection of paintings of the front entrance to each tomb in the Valley of the Kings.

1830

In 1830, Wilkinson published all of his entrance drawings and maps in his book Suitable Topography, as well as a complete survey of other tombs in Egypt.

After Wilkinson published his paintings, James Burton led expeditions in the Valley of the Kings. James Burton was known to have entered the tombs of the sons of Ramesses II, but the goal of his continued work was to protect the tombs of Seti I from flooding.

1829

In 1829, Champollion visited the Valley of the Kings as part of Franco’s campaign to explore beyond Tuscany. Theologians Ippolito Rossellini and Nestor spent nearly two months in the Valley of the Kings examining the tombs, 16 of which were found at the time.

The total number of tombs was yet to be discovered, but the inscriptions carved on the walls identified the original owners of the tombs. Several wall inscriptions from the tomb of Seti I are now on display at the Louvre in Paris. However, the wall was badly damaged during the excavations.

1845 and 1846

In 1845 and 1846, Carl Richard Lepsius visited the valley with incredible force and determination. He documented 25 tombs in the eastern Valley of the Kings and four in the western valley.

1888

At the beginning of 1888, sixteen tombs were discovered by Juli, George and Victor Loret. Meanwhile, George Darissi opened the tombs of Ramses V and Ramses VI.

Gaston Maspero, the chief of the Valley of the Kings expedition and the leader of the historians studying ancient rulers of Egypt, was relieved from his position in the region when better excavation methods were discovered.

The 20th Century

In the early 20th century, American lawyer Theodore Davis obtained permission from the Egyptian government to search and excavate the area. His team, led by British Egyptologist Edward Russell Ayrton, examined many royal and non-royal tombs, including Tombs 43, 46 and 57.

They also found evidence of the Amarna Cemetery in Tomb 55, after which they excavated Tutankhamun’s remains in two tombs, Tomb 54 and Tomb 58. Upon finishing, they declared that it would be impossible to fully explore the Valley of the Kings and that endless tombs and artefacts were buried there.

1912-1922

In 1912, Theodore Davis published a book entitled The Tombs of Harmhabi and Tuatankhamu about the expedition. He added comments on his latest discoveries on the book’s last page. After Davies died in early 1915, George Herbert (5th Earl of Carnarvon) obtained exploration and excavation rights in the Valley of the Kings.

He appointed Howard Carter to lead his team of explorers. The group took off and discovered the tomb of Tutankhamun, known as Tomb 62, in November 1922. A project planned in Thebes at the end of the 20th century could be based on the discovery of Tomb 5 of the sons of Ramesses II.

Tomb 5 was located in the largest of the two districts of the Valley of the Kings. It housed 120 rooms for funerals and tombs. The project also explored and restored many valley tombs to the east or west.

Today, research is underway to determine if the tomb is empty or if the sons of Ramesses II are actually buried there.

1923-2002

The Amarna Royal Cemeteries Project surveyed the area around both Tombs 55 and 62 to identify the burial sites of the Amarna-era kings. This excavation project took a long time to complete due to the vast area and intricate methods used in order to not harm or destroy the tombs.

The 21st Century

In the twenty-first century, many expeditions have continued to excavate and explore the area. This includes the beginning of the Thebes Planning Project in 2001.

Many accompanying surveys added a wealth of information and facts about the area, providing information and maps of the tombs found. The Valley of the Kings is currently open to the public for tourism but is sometimes closed for maintenance and restoration.

February 2006

In a press release dated 8 February 2006, the Supreme Council of Antiquities informed the public that the first pharaoh’s tomb (Tomb 63) was discovered at the Valley of the King. It was found by a team of University of Memphis researchers who had travelled to Egypt to study the country.

After the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb and mummy in 1922, the seven assembly machines placed a few metres away were used to survey the area. This valley was decorated with seven large deposits, had a single entry space, and was not used for tombs.

May 2008

In May 2008, Zahi Hawass announced that he had commissioned an Egyptian research team to search for the tomb of Pharaoh Ramesses VIII in the area around the tombs of Merneptah and Ramesses II. Of the 61 people on the team, none were able to find the tomb.

Instead, they focused their observations on the earth stairs that led to this set of graves. Once they excavated and descended down the stairs, the group arrived in a room without a suspension chamber.

It is believed that this space served several purposes. Some rooms were meant to bury the centre of Kingdom Loar, while others were prodigals, and others were completely empty. This set of archaeological excavations has become one of the most intense in the field.

Tourism in the Valley of the Kings

Tourism in the Valley of the Kings, located on the west bank of the Nile River near Luxor, Egypt, plays a pivotal role in the cultural and economic landscape of the region. The Valley of the Kings is renowned worldwide for its historical significance and the breathtaking treasures it houses, making it a magnet for tourists from across the globe.

This unique archaeological site provides a window into the splendours of ancient Egypt and offers an unforgettable experience for those seeking to explore the mysteries of the pharaohs.

One of the most striking aspects of tourism in the Valley of the Kings is its contribution to the local and national economy. The steady influx of tourists brings with it revenue that fuels the local businesses and the wider Egyptian tourism industry.

Visitors to the Valley often stay in the nearby city of Luxor, patronizing hotels, restaurants, and other services, thus generating income and employment opportunities for the local population.

Additionally, the revenue generated from entrance fees and guided tours at the Valley of the Kings plays a crucial role in funding ongoing archaeological research, site preservation, and conservation efforts. This ensures that this invaluable heritage remains accessible for future generations.

Moreover, tourism in the Valley of the Kings facilitates cultural exchange and education. Visitors from around the world have the opportunity to witness the magnificence of Egyptian history up close. The site’s tombs, adorned with intricate murals and hieroglyphs, serve as an educational resource, offering insights into the religious beliefs, artistry, and daily life of ancient Egypt.

This exchange of knowledge and culture enriches the experiences of both tourists and the local community, fostering a greater understanding of Egypt’s heritage.

However, the surge in tourism also brings challenges, notably regarding the preservation of the site. The increased foot traffic and exposure to the elements pose threats to the fragile tombs and their intricate decorations.

To mitigate these risks, experts, archaeologists, and curators work tirelessly to protect and restore the ancient treasures while maintaining accessibility to tourists. Careful management and visitor regulations are essential to balance between tourism and preservation.

Through this balance, the Valley of the Kings can continue to be a beacon of ancient Egyptian history, offering visitors an awe-inspiring journey through time while contributing to the prosperity of the local community and the nation as a whole.

Other Tourist Attractions to See When You Visit the Valley of the Kings

The region surrounding the Valley of the Kings in Egypt is not only home to this iconic archaeological site but also hosts many other compelling tourist attractions that comprehensively explore Egypt’s rich history and culture.

Karnak Temple

Among these sites, the nearby Karnak Temple Complex stands out as one of the most impressive and sprawling open-air museums in the world. Just a short distance from the Valley of the Kings, Karnak is a vast temple complex dedicated to the god Amun, and it features an astonishing array of colossal statues, towering columns, and intricate hieroglyphics.

Luxor Temple and Museum

Luxor Temple, another gem in the vicinity, is equally significant and accessible to tourists. Located on the east bank of the Nile, this temple is a masterpiece of Pharaonic architecture and artistry. It served as a religious centre in ancient times and boasts a beautiful avenue of sphinxes leading to its entrance.

For those interested in the mysteries of ancient Egypt beyond the Valley of the Kings, the Luxor Museum is a must-visit destination. This museum showcases an impressive collection of artefacts, many of which were discovered in the nearby tombs and temples.

It offers a unique opportunity to view exquisite statues, jewellery, and everyday objects from various periods of Egypt’s history, providing an intimate encounter with the past.

Temple of Hatshepsut

Another intriguing site close to the Valley of the Kings is the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut. This temple, dedicated to one of Egypt’s most fascinating female pharaohs, Queen Hatshepsut, is a marvel of ancient architecture nestled amidst towering cliffs.

The temple’s design and location make it an extraordinary blend of nature and human ingenuity, offering a glimpse into the role of women in ancient Egyptian society.

Nile Cruises

Additionally, a leisurely cruise along the Nile River is a captivating way to experience the beauty of the landscape and explore more historical sites. Many cruises offer stops at temples, villages, and historic sites along the Nile’s banks, making it a comprehensive journey through Egypt’s history and culture.

The Valley of the Kings is not an isolated attraction but the heart of a region rich in historical, architectural, and cultural wonders. The surrounding sites collectively create a multifaceted experience that allows tourists to immerse themselves in the splendid tapestry of ancient Egypt.

The Valley of the Kings is one of Egypt’s Best Tourist Attractions

The Valley of the Kings in Egypt is an unparalleled testament to the grandeur of ancient Egyptian civilization. This sacred burial ground has given the world unique insights into the beliefs, customs, and artistic achievements of a civilization that flourished thousands of years ago.

The excavation history of the Valley of the Kings, filled with groundbreaking discoveries, has left an incredible mark on the field of archaeology. Ongoing excavations, restoration efforts, and responsible tourism are pivotal in preserving the Valley’s heritage for future generations.

Moreover, the appeal of the Valley of the Kings is amplified by the presence of neighbouring attractions like the Karnak Temple Complex and the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut. These sites enhance the tourist experience by offering a comprehensive journey through ancient Egypt’s history, culture, and architectural marvels.

As we stand on the cusp of a new era of studying and appreciating Egypt’s treasures, it is crucial to recognize the delicate balance between preserving the past and sharing it with the world. With its rich history and vibrant attractions, the Valley of the Kings invites us to marvel at the accomplishments of an ancient civilization and the timeless allure of Egypt’s cultural heritage.

If you’re interested in visiting Egypt, check out our blog on Aswan: 10 Reasons You Should Visit Egypt’s Land of Gold.