The Nile River, Egypt’s Most Enchanting River

Updated On: April 18, 2024 by Ciaran Connolly

Hello there, fellow explorer! Are you looking for information about the Nile River? Well, then, you’ve come to the right place. Let me show you around. The Nile is a major river in northeastern Africa, flowing north.

It drains into the Mediterranean Sea. Until recently, it was thought to be the world’s longest river, but new research shows that the Amazon River is just a tad longer. The Nile is one of the world’s smaller rivers, measured in cubic metres of water per year.

Over the course of its ten-year life span, it drains eleven countries: In the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda, Ethiopia, Eritrea, South Sudan, The Republic of Sudan

It is approximately 6,650 kilometres (4,130 mi) in length. The Nile is the primary source of water for all three countries in the Nile basin. Fishing and farming are also supported by the Nile, which is a major economic river. The Nile has two major tributaries: the White Nile, which originates near Lake Victoria, and the Blue Nile.

The White Nile is commonly regarded as the primary tributary. According to a study published in the Journal of Hydrology, 80 percent of the Nile’s water and silt originate from the Blue Nile.

The White Nile is the longest river in the Great Lakes region and is rising in elevation. In Uganda, South Sudan, and Lake Victoria, it all begins. Flowing from Ethiopia’s Lake Tana into Sudan, the Blue Nile is the longest river in Africa.

In Khartoum, Sudan’s capital, the two rivers meet. The annual flooding of the Nile has been critical to Egyptian and Sudanese civilizations since the beginning of time. The Nile flows almost entirely north to Egypt and its large delta, where Cairo sits on it, before emptying into the Mediterranean Sea at Alexandria in Egypt.

The majority of Egypt’s major cities and population centres are located north of the Aswan Dam in the Nile Valley. All of Ancient Egypt’s archaeological sites were built along riverbanks, including the majority of the country’s most important ones.

The Nile, along with the Rhône and Po, is one of the three Mediterranean rivers with the most water discharge. At 6,650 kilometres (4,130 miles), it is one of the world’s longest rivers and flows from Lake Victoria to the Mediterranean Sea.

The drainage basin of the Nile covers around 3.254555 square kilometres (1.256591 square miles), which is equivalent to approximately 10% of the land area of Africa. However, in comparison to other major rivers, the Nile transports relatively little water (5 percent of the Congo River, for example).

There are many variables that affect the discharge of the Nile basin, including weather, diversion, evaporation, evapotranspiration, and groundwater flow. Known as the White Nile upstream from Khartoum (to the south), it is also used to refer to the area between Lake No and Khartoum in a more specific sense.

Khartoum is where the Blue Nile meets the Nile River. The White Nile originates in Equatorial East Africa, while the Blue Nile originates in Ethiopia. Both branches of the East African Rift can be found on its western flanks. It’s time to talk about a different source here.

The terms “source of the Nile” and “source of the Nile bridge” are used interchangeably here. At this point of year on Lake Victoria, One of the most important tributaries to the present-day Nile River is the Blue Nile, while the White Nile contributes far less water.

Still, the White Nile remains a mystery even after centuries of investigation. In terms of distance, the closest source is the Kagera River, which has two known tributaries and is, without a doubt, the origin of the White Nile.

The Ruvyironza River (also known as the Luvironza River) and the Rurubu River are the tributaries of the Ruvyironza River. The Blue Nile’s headwaters are found in Ethiopia’s Gilgel Abbay watershed in the Highlands. The source of the Rukarara tributary was discovered in 2010 by a team of scientists.

It was discovered that the Nyungwe forest had a large inflowing surface flow for many kilometres upstream by cutting an access path up steep, jungle-covered mountain slopes during the dry season, giving the Nile an additional 6,758 kilometres (4,199 mi).

A Nile of Legends

According to legend, Gish Abay is where the first drops of the Blue Nile’s “holy water” form. Aswan High Dam in Egypt is the northernmost point of Lake Nasser, where the Nile resumes its historic course.

The Nile’s western and eastern branches (or distributaries) feed the Mediterranean north of Cairo, forming the Nile Delta, which is made up of both the Rosetta and Damietta branches. Near Bahr al Jabal, a small town south of Nimule, the Nile enters South Sudan (“Mountain River”).

A short distance south of town is where it joins the Achwa River. It’s at this point that the Bahr al Jabal, a 716-kilometer (445-mile) river, meets the Bahr al Ghazal, and it’s at this point that the Nile is known as the Bahr al Abyad, or White Nile.

As a result of the rich silty deposit left behind when the Nile floods, fertilisers are applied to the soil. The Nile no longer floods Egypt since the completion of the Aswan Dam in 1970. As the Bahr al Jabal section of the Nile empties into the White Nile, a new river, the Bahr el Zeraf, begins its journey.

At an average of 1,048 m3/s (37,000 cu ft/s), the Bahr al Jabal at Mongalla, South Sudan, flows year round. South Sudan’s Sudd region is reached by the Bahr Al Jabal after passing through Mongalla.

Over half the Nile’s water is evaporated in this swamp due to evaporation and transpiration. The average flow rate in the White Nile’s tailwaters is approximately 510 m3/sec (18,000 ft/sec). Following its departure from this point, the Sobat River joins it in Malakal.

Upstream of Malakal is the source of approximately 15 percent of the yearly Nile outflow from the White Nile. Averaging 924 m3/s (32,600 cu ft/s) and peaking at 1,218 m3/s (43,000 cu ft/s) in October, the White Nile flows at Lake Kawaki Malakal, just below the Sobat River.

The lowest flow is 609 m3/s (21,500 cft/s) in April. At its lowest, the Sobat’s flow is 99 m3/s (3,500 cubic feet per second) in March; at its highest, it reaches 680 m3/s (24,000 cubic feet per second) in October.

As a result of this change in flow, there is this fluctuation. Between 70 and 90 percent of Nile discharge in the dry season comes from the White Nile (January to June). The White Nile flows through Sudan between Renk and Khartoum, where it meets the Blue Nile. The Nile’s path through Sudan is unusual.

From Sabaloka, north of Khartoum, to Abu Hamed, it flows over six groups of cataracts. In response to the tectonic uplift of the Nubian Swell, the river is diverted to flow more than 300 kilometres south-west along the Central African Shear Zone.

The Great Bend of the Nile, which Eratosthenes had already described, is formed when the Nile resumes its northward course at Al Dabbah to reach the first cataract at Aswan. The river flows into Lake Nasser, also known as Lake Nubia in Sudan, which is located primarily in Egypt.

Uganda is home to the White Nile. At Ripon Falls, near Jinja, Uganda, the Victoria Nile emerges from Lake Victoria and flows into the Nile River. There is a 130-mile (81-kilometer) journey to get to Lake Kyoga.

Once it leaves the shores of Lake Tanganyika on the west, the final 200 kilometres (120 miles) of the roughly 200-kilometer-long river begin to flow to the north. To the east and north, the river makes a significant half-circle until it reaches Karuma Falls.

Only a small portion of the Murchison continues to flow west through Murchison Falls until it reaches the northern shores of Lake Albert. Although the Nile is not currently a border river, the lake itself lies on the DRC’s border.

After exiting Lake Albert, the river is known as the Albert Nile as it makes its way north through Uganda. Only a small tributary, known as the Atbara River, originates in Ethiopia north of Lake Tana and joins the Blue Nile below the confluence.

It’s about half-way to the sea and has a length of about 800 kilometres. Ethiopia’s Atbara River only flows during the rainy season, and even then it quickly dries up. The dry season typically occurs from January to June north of Khartoum.

In the vicinity of the Ethiopian city of Bahir Dar, Lake Tana, a major water source for the Blue Nile Falls, can be found.depiction of dust storms in the Red Sea and Nile, with annotations. Khartoum is where the Blue and White Nile rivers meet and converge to form what is known as “the Nile.”

The Blue Nile contributes 59 percent of the Nile’s water, while the Tekezé, Atbarah, and other minor tributaries contribute the remaining 42 percent. Ninety percent of the Nile’s water and 96 percent of its carried silt originate in Ethiopia.

Since Ethiopia’s major rivers (Sobat, Blue Nile, Tekezé, and Atbarah) flow more slowly most of the year, erosion and silt transport only occur during the Ethiopian rainy season, when rainfall on the Ethiopian Plateau is particularly heavy.

During dry and harsh seasons, the Blue Nile is completely dried up. The large natural variations in Nile flow are largely due to the Blue Nile’s flow, which varies greatly over the course of its annual cycle.

A natural discharge of 113 cubic metres per second (4,000 cubic feet per second) is possible in the Blue Nile during the dry season, even though upstream dams control the river’s movement. The peak flow of the Blue Nile is usually 5,663 m3/s (200,000 cu ft/s) or more in late August, during the rainy season (a difference of a factor of 50).

There was a 15-fold variation in Aswan’s annual discharge before the river’s dams were built. This year’s peak flow was 8,212 m3/s (290,000 cu ft/s), and the lowest was 552 m3/s (19,500 cu ft/s) in late August and early September. The streams of the Sobat and Bahr el Ghazal rivers

Two of the White Nile’s most important tributaries discharge their waters into the Bahr al Ghazal and Sobat rivers. Due to the enormous amounts of water that are lost in the Sudd wetlands, the Bahr al Ghazal only contributes a small amount of water each year—roughly 2 cubic metres per second (71 cubic feet per second)—due to the enormous amounts of water that are lost in the Bahr al Ghazal.

The Sobat River drains only 225,000 km2 (86,900 sq miles), but it contributes 412 cubic metres per second (14,500 cu ft/s) annually to the Nile. Near the bottom of Lake No. 1, it joins the Nile. Sobat floods make the White Nile’s colour even more vibrant because of all the sediment it brings with it.

Map of the Yellow: In contemporary Sudan, the Nile’s tributaries are called the Nile Yellow. As an ancient tributary of the Nile, it was once used to connect eastern Chad’s Ouadda Mountains with the Nile Valley between 8000 and 1000 BCE.

One of the names given to its ruins is Wadi Howar. At its southern end, the wadi joins the Nile in Gharb Darfur, which is close to its northern border with Chad. A reconstruction of the Oikoumene (inhabited world) was created around 450 BC, based on Herodotus’ description of the world at the time.

With most of Egypt’s population and major cities located along the Nile Valley’s sections north of Aswan since prehistoric times (iteru in Ancient Egyptian), the Nile has been the lifeblood of Egyptian civilization.

There is evidence that the Nile used to enter the Gulf of Sidra in a much more westward direction through what are now Libya’s Wadi Hamim and Wadi al Maqar. At the end of the last ice age, the northern Nile snatched the ancient Nile near Asyut, Egypt, from the southern Nile.

The current Sahara desert was formed as a result of a climate shift that occurred around 3400 BC. Niles in his infancy:

The Upper Miocenian Eonile, which began approximately 6 million years ago (BP), the Upper Pliocenian Paleonile, which began approximately 3.32 million years ago (BP), and the Nile phases during the Pleistocene are the five earlier phases of the current Nile.

About 600,000 years ago, there was a Proto-Nile. Then there was a Pre-Nile, and then a Neo-Nile. Using satellite imagery, dry watercourses in the desert west of the Nile flow north from Ethiopia’s Highlands, were discovered. There’s a canyon in the area where the Eonile once ran that’s been filled in by surface drift.

Eonile sediments transported to the Mediterranean have been found to contain several natural gas fields. The Mediterranean Sea evaporated to the point where it was nearly empty, and the Nile redirected itself to follow the new base level until it was several hundred metres below world ocean level at Aswan and 2,400 metres (7,900 ft) below Cairo.

During the late Miocene Messinian salinity crisis, the Nile changed its course to follow the new base level. Thus, an enormous and deep canyon was formed, which had to be filled with sediment after the Mediterranean was rebuilt.

When the riverbed was raised by sediments, it overflowed into a depression west of the river and formed Lake Moeris. After Rwanda’s Virunga Volcanoes cut off Lake Tanganyika’s path to the Nile, it flowed southward.

The Nile had a longer course back then, and its source was located in northern Zambia. The current flow of the Nile was established during the Würm glaciation period. With the help of the Nile, there are two competing hypotheses as to how old the integrated Nile is.

That the Nile basin used to be divided into several distinct areas, only one of which fed a river that followed the current course of Egypt and Sudan, and that only the most northerly of these basins was connected to Egypt and Sudan’s current Nile River.

Early on, Egypt supplied most of the Nile’s water supply, according to Rushdi Said’s hypothesis.

Alternatively, it is proposed that Ethiopian drainage via rivers like the Blue Nile, the Atbara, and the Takazze, which are comparable to the Egyptian Nile, has flowed to the Mediterranean since at least Tertiary times.

In the Paleogene and Neoproterozoic eras (66 million to 2.588 million years ago), Sudan’s Rift System included the Mellut, White, Blue, and Blue Nile Rifts, as well as the Atbara and Sag El Naam Rifts.

There is a depth of nearly 12 kilometres (7.5 miles) in the centre of the Mellut Rift Basin. Tectonic activity has been observed on both the northern and southern margins of this rift, suggesting that it is still in motion.

A sinking Sudd swamp is a possible outcome of climate change in the basin’s centre. In spite of its shallow depth, the White Nile Rift System remains about 9 kilometres (5.6 miles) below the surface of the Earth.

The Blue Nile Rift System’s geophysical research estimated the depth of the sediments to be 5–9 kilometres (3.1–5.6 miles). As a result of rapid sediment deposition, these basins were able to connect even before their subsidence ceased.

It is believed that the Ethiopian and Equatorial headwaters of the Nile have been captured during the current phases of tectonic activity in the Eastern, Central, and Sudanese Rift Systems. The Egyptian Nile: At certain times of year, the Nile’s various branches were connected.

Between 100,000 and 120,000 years ago, the Atbara River overflowed its basin, resulting in the flooding of the surrounding land. The Blue Nile joined the main Nile during the wet period between 70,000 and 80,000 years B.P.

Ancient Egyptians farmed and traded a variety of crops along the Nile’s banks, including wheat, flax, and papyrus. Wheat was an essential crop in the Middle East, which was plagued by famine.

Egypt’s diplomatic ties with other countries were preserved thanks to this trading system, which helped to keep the economy stable. Traders have operated along the Nile for millennia.

When the Nile River began to flood in Ancient Egypt, the people of the country wrote and sung a song called “Hymn to the Nile” in celebration. The Assyrians imported camels and water buffalo from Asia around 700 BCE.

In addition to being slaughtered for their meat or being used to plough fields, these animals were also used for transportation. It was essential to the survival of both humans and livestock. People and goods could be transported efficiently and cheaply along the Nile.

Ancient Egyptian spirituality was heavily influenced by the Nile River. In ancient Egypt, the yearly flood deity, Hapi, was worshipped alongside the monarch as a co-author of nature’s fury. The Nile was seen as a gateway between the afterlife and death by the ancient Egyptians.

A location of birth and growth and a place of death were viewed as opposites in the ancient Egyptian calendar, which depicted the sun god Ra as he traversed the sky each day. All tombs in Egypt were located west of the Nile because the Egyptians believed that one must be buried on the side that represents death in order to access the afterlife.

A three-cycle calendar was devised for the ancient Egyptians to honour the importance of the Nile in Egyptian culture. There were four months in each of these four seasons; each had a 30-day duration.

Agriculture thrived in Egypt thanks to the fertile soil that was left behind by the Nile flooding during Akhet, which means inundation. During Shemu, the final harvest season, there was no rain.

Grown-ups were out in force during this time. John Hanning Speke was the first European to hunt for the Nile’s source in 1863. When Speke first set foot on Lake Victoria in 1858, he returned to identify it as the source of the Nile in 1862.

A lack of access to South Sudan’s wetlands prevented ancient Greeks and Romans from exploring the upper White Nile. There have been numerous failed attempts to locate the river’s source.

In contrast, no ancient Europeans have ever been found around Lake Tana. It was during the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus that a military expedition made it far enough along the Blue Nile’s course to ascertain that the summer floods were caused by severe seasonal rainstorms in the Ethiopian Highlands.

The Tabula Rogeriana, dated 1154, listed three lakes as the sources. It was in the fourteenth century that the Pope dispatched monks to Mongolia to serve as emissaries and report back to him that the Nile’s origin was in Abyssinia.

This was the first time Europeans learned where the Nile originates (Ethiopia). Ethiopian travellers in the late fifteenth and sixteenth centuries visited Lake Tana and the Blue Nile’s source in the mountains to the south of the lake.

A Jesuit priest named Pedro Páez is acknowledged as the first European to reach its source, despite allegations by James Bruce that it was an American missionary. According to Páez, the origin of the Nile can be traced back to Ethiopia.

Páez’s contemporaries, like Baltazar Téllez, Athanasius Kircher, and Johann Michael Vansleb, all mentioned it in their writings, but it wasn’t published in its entirety until the early twentieth century.

As early as the mid-fifteenth century, Europeans settled in Ethiopia, and it is possible that one of them travelled as far upstream as possible without leaving any records behind. After comparing these falls to the Nile River Falls recorded in Ciceros De Republica, Portuguese writer Joo Bermude first wrote about Tis Issat in his 1565 autobiography.

In the wake of Pedro Páez’s arrival, Jerónimo Lobo explains the Blue Nile’s origin. In addition to Telles, he also had an account. The White Nile was much less well-known. The ancients mistook the Niger River’s higher reaches for those of the White Nile.

If you’re looking for a specific example, Pliny the Elder claims that the Nile began in a Mauretania mountain, flowed above ground for “many days,” submerged, resurfaced as an enormous lake in the Masaesyli territory, and then sank once more beneath the desert to flow underground for “a distance of 20 days’ journey until it reaches the closest Ethiopians.”

Around 1911, a chart of the Nile’s primary stream, which ran through British occupations, condominiums, colonies, and protectorates, claimed that the Nile’s water attracted buffalo. For the first time in modern times, the Nile Basin began to be explored after the Ottoman Viceroy of Egypt and his sons conquered northern and central Sudan in 1821.

The White Nile was known up to the Sobat River, whereas the Blue Nile was known up to Ethiopia’s foothills. To navigate through the treacherous terrain and fast-moving rivers beyond the present-day port of Juba, Turkish lieutenant Selim Bimbashi led three expeditions between 1839 and 1842.

In 1858, British explorers John Hanning Speke and Richard Francis Burton arrived at Lake Victoria’s southern shore while searching for the great lakes in central Africa. At first, Speke thought he had found the source of the Nile and named the lake after the British monarch in charge at the time, King George VI.

Even though Speke claimed to have proved that his discovery was indeed the source, Burton remained sceptical and thought it was still open to debate. On the banks of Lake Tanganyika, Burton was recuperating from an illness.

After a highly publicised squabble, scientists and other explorers alike became interested in confirming or disputing Speke’s discovery. British explorer and missionary David Livingstone ended up in the Congo River system after going too far west.

Henry Morton Stanley, a Welsh-American explorer who had previously circumnavigated Lake Victoria and recorded the enormous discharge at Ripon Falls on the lake’s northern bank, was finally the one to corroborate Speke’s discoveries.

Historically, Europe has been deeply interested in Egypt since Napoleon’s reign. Liverpool’s Laird Shipyard built an iron boat for the Nile river in the 1830s. The Suez Canal’s opening and the British occupation of Egypt in 1882 led to more British river steamers.

The Nile is the region’s natural waterway and gives steamer access to Sudan and Khartoum. In order to recapture Khartoum, specially built sternwheelers from England were sent over and steamed up the river.

That was the beginning of regular river steam navigation. During World War I and the intervening years, river steamers operated in Egypt to offer transportation and protection to Thebes and the Pyramids.

Even in 1962, steam navigation was still a major mode of transportation for both countries. Due to Sudan’s lack of road and rail infrastructure, steamboat commerce was a lifeline. Most paddle steamers have been abandoned for shorefront service in favour of modern diesel tourist vessels still operating on the river. ’50 and thereafter:

Rivers Kagera and Ruvubu come together at Rusumo Falls, in the Nile’s high reaches. On the Nile, dhows. The Nile flows through Cairo, Egypt’s capital city. Cargo has historically been transported down the Nile’s whole length.

As long as the winter winds from the south aren’t too strong, ships can go up and down the river. While most Egyptians still live in the Nile Valley, the Aswan High Dam’s 1970 completion profoundly transformed agricultural practises by stopping summer floods and regenerating the fertile land underneath them.

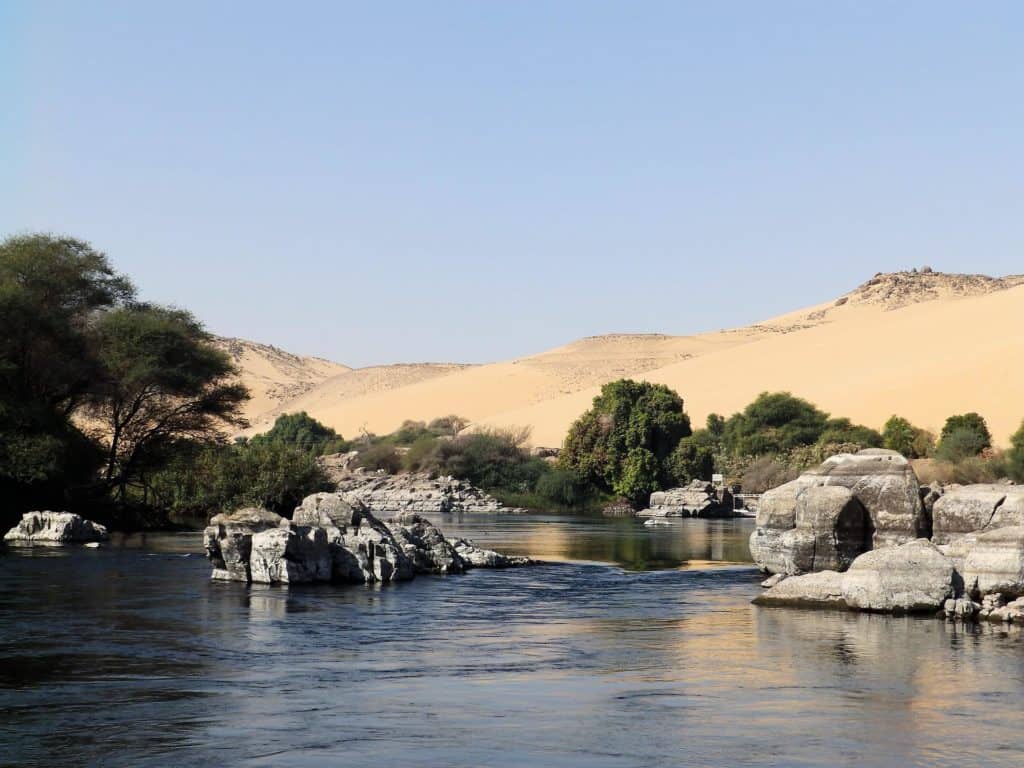

While much of the Sahara is uninhabitable, the Nile provides food and water for the Egyptians who live along its banks. River flow is disrupted multiple times by the cataracts of the Nile, which are areas of fast-moving water with numerous small islands, shallow water, and boulders that make it difficult for boats to navigate.

As a result of the Sudd marshes, Sudan attempted canalization (the Jonglei Canal) in order to circumvent them. This was a disastrous attempt. Nile cities include Khartoum, Aswan, Luxor (Thebes), and the conurbation of Giza and Cairo. There is a first cataract in Aswan, which is located to the north of the Aswan Dam.

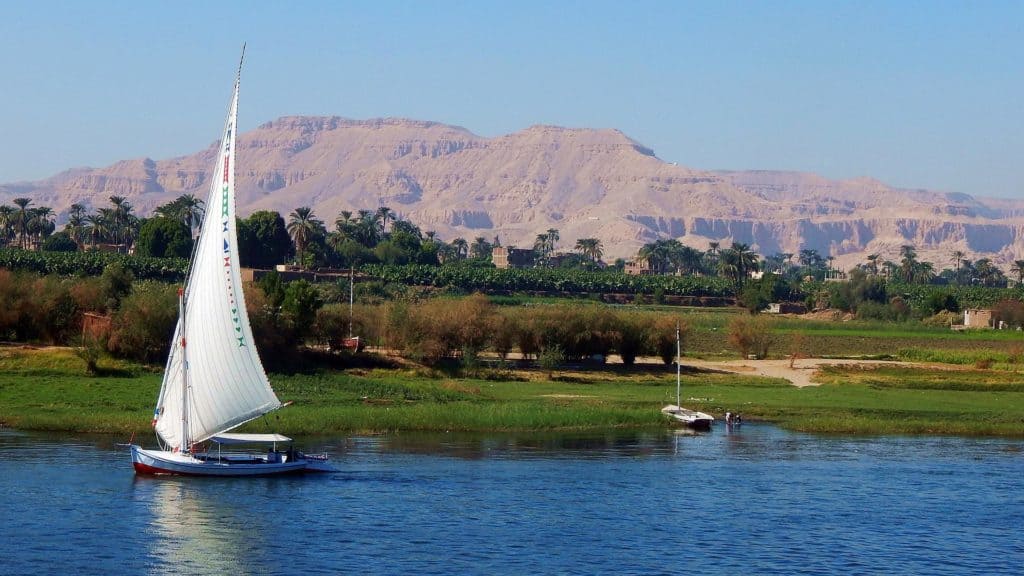

Cruise ships and feluccas, traditional wooden sailing ships, frequent this portion of the river, making it a popular tourist destination. Many cruise ships call at Edfu and Kom Ombo on the route from Luxor to Aswan.

Due to security concerns, northern cruising has been prohibited for many years. For the Ministry of Hydropower in the Sudan, HAW Morrice and W.N. Allan oversaw a computer simulation study between 1955 and 1957 in order to plan the economic development of the Nile.

Morrice was their hydrological advisor, and Allan was Morrice’s predecessor in the position. In charge of all computer-related activities and software development was MP Barnett. The calculations were based on accurate monthly inflow data gathered over a 50-year period.

It was the over-year storage method that was used to save water from the wet years for use in the dry ones. Navigation and irrigation were both taken into consideration. As the month progressed, each computer run proposed a set of reservoirs and operating equations for releasing water.

Modelling was used to predict what would have happened if the input data had been different. More than 600 different models were tested. Sudanese officials received advice. The calculations were done on an IBM 650 computer.

To learn more about the simulation studies used to design water resources, check out the article on hydrology transport models, which have been in use since the 1980s to analyse water quality.

Although many reservoirs were built during the 1980s drought, Ethiopia and Sudan suffered widespread starvation, but Egypt reaped the benefits of the water that was stocked in Lake Nasser.

In the Nile river basin, drought is a leading cause of death for many people. It’s estimated that 170 million people have been affected by droughts in the last century, and 500,000 people have died as a result.

Ethiopia, Sudan, South Sudan, Kenya, and Tanzania collectively accounted for 55 of the 70 drought-related incidents that occurred between 1900 and 2012. Water acts as a divider in a dispute.

Dams on the Nile River (plus a huge dam under construction in Ethiopia). For many years, the Nile’s water has influenced East Africa’s and the Horn of Africa’s political landscape. Egypt and Ethiopia are embroiled in a dispute over $4.5 billion.

Inflamed nationalist sentiments, deep-seated anxieties, and even war rumours have been stoked over the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam. In the wake of Egypt’s monopoly on Egypt’s water resources, other countries have expressed their displeasure.

As part of the Nile Basin Initiative, these countries are urged to cooperate peacefully. There have been various attempts to reach an agreement among the countries that share the Nile’s waters.

A new water-sharing agreement for the Nile River was signed May 14 in Entebbe by Uganda, Ethiopia, Rwanda, and Tanzania, despite strong opposition from Egypt and Sudan. Accords like these should help to promote the equitable and efficient use of the Nile basin’s water resources.

Without a better understanding of the future water resources of the Nile, conflicts could occur between these nations that rely on the Nile for their water supply, economic development, and social progress.

Modern Nile advances and exploration. White: An American-French expedition in 1951 was the first to cross the Nile River from its source in Burundi through Egypt to its mouth on the Mediterranean Sea, a distance of approximately 6,800 kilometres (4,200 mi).

This journey is documented in the book Kayaks Down the Nile. This 3,700-mile-long White Nile Expedition was led by South African Hendrik Coetzee, who was the expedition’s captain (2,300 mi).

As of January 17, 2004, the expedition had arrived at Rosetta, a Mediterranean port four and one-half months after it left Lake Victoria in Uganda. The colour of the Nile, Nile Blue,

It was geologist Pasquale Scaturro, along with his kayaker and documentary filmmaker partner Gordon Brown, who led the Blue Nile Expedition from Ethiopia’s Lake Tana to Alexandria’s Mediterranean shores.

A total of 5,230 kilometres were traversed during their 114-day journey that began on December 25th, 2003, and ended on April 28th, 2004, (3,250 miles).

It was only Brown and Scaturro who made it to the end of their journey, despite the fact that they were joined by others. Even though they had to navigate whitewater manually, outboard motors were used for the majority of the team’s trip.

On January 29, 2005, Les Jickling of Canada and Mark Tanner of New Zealand completed the first human-powered transit of Ethiopia’s Blue Nile. Five months and more than 5,000 kilometres later, they arrived at their destination (3,100 miles).

During their journey through two conflict zones and areas known for their bandit populations, they recall being detained at gunpoint. One of the world’s most important rivers, the Nile, is called Bar Al-Nil or Nahr Al-Nil in Arabic.

A river that originates in southern Africa and flows through northern Africa empties into the Mediterranean Sea in the northeast. About 4,132 miles long, it drains an area of approximately 1,293,000 square miles (3,349,000 square kilometres).

A large portion of Egypt’s cultivated land is located in the basin of this river. In Burundi, the river’s furthest source is the Kagera River. The three major rivers that feed into Lakes Victoria and Albert are the Blue Nile (Arabic: Al-Bar Al-Azraq; Amharic: Abay), the Atbara (Arabic: Nahr Abarah), and the White Nile (Arabic: Al-Bar Al-Abyad).

It’s all about the water. No matter how many states have water, there is only one correct answer to each question on this test. Take a dive into the water and see if you sink or swim. Take a look at the flow of the Nile, the world’s longest river.

The Flow of the Nile

Observe the world’s longest river, the Nile, flow. The Nile in 2009, as captured in this photograph. ZDF Enterprises GmbH, Mainz, and Contunico are all responsible for the video content found below.

The name Neilos (Latin: Nilus) comes from the Semitic root naal (valley or river valley) and, by extension, a river because of this meaning. Old Egypt and Greece had no idea why the Nile flowed northward from the south in contrast to other well-known large rivers and when it was overflowing during the hottest months of the year.

The ancient Egyptians referred to the river Ar or Aur (Coptic: Iaro) as “Black” because of the colour of the sediments it carried during floods. Both Kem and Kemi mean “black” and denote darkness, and are derived from the Nile mud that covers the area.

The Egyptians (feminine) and their tributary, the Nile (masculine), are both referred to as Aigyptos in Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey by the Greek poet (7th century BCE). Current names for the Nile include Al-Nil, al Bar, and al Bar or Nahr Al-Nil in Egypt and Sudan.

The Nile River basin, which covers a tenth of Africa’s landmass, was home to some of the world’s most advanced civilizations, many of which eventually fell into ruin. Many of these people lived along the banks of the river. As early farmers and plough users, many of these people lived

The Marrah Mountains of Sudan, the Al-Jilf al-Kabr Plateau of Egypt, and the Libyan Desert form a less well-defined watershed that separates the Nile, Chad, and Congo basins on the western side of the basin.

East Africa’s East African Highlands, which include Lake Victoria, the Nile, and the Red Sea Hills and Ethiopian Plateau, encircle the basin to the north, east, and south (part of the Sahara). Since water from the Nile is available all year round and the area is hot, intensive farming is feasible along its banks.

Even in regions where the average rainfall is sufficient for cultivation, significant annual variations in precipitation can make cultivating without irrigation a risky undertaking. A presidential pension was established by Congress because President Harry S. Truman’s post-presidency earnings were so low.

Get Access to All of the Helpful Data: Additionally, the Nile River serves as a vital waterway for transportation, particularly during times when motorised transportation is impractical, such as during the flood season.

As a result, reliance on waterways has decreased significantly since the turn of the 20th century as a result of improvements in air, rail, and highway infrastructure. The physiography of the Nile River: About 30 million years ago, the early Nile, which was a much shorter stream, is thought to have had its sources in the area between 18° and 20° N latitude.

The current Atbara River may have been its primary tributary back then. There was a large lake and an extensive drainage system to the south. It’s possible that an outlet to Lake Sudd was created around 25,000 years ago, according to one theory about the development of the Nile system in East Africa.

After a long period of sediment buildup, the lake’s water level rose to the point where it overflowed and spilled into the northern part of the basin. Formed into a riverbed, Lake Sudd’s overflow water connected the two major parts of the Nile system. This included the flow from Lake Victoria to the Mediterranean Sea, which was previously separate.

The Nile basin is divided into seven main geographical regions: the Lake Plateau of East Africa, the Al-Jabal (El-Jebel), the White Nile (also known as the Blue Nile), the Atbara River, and the Nile north of Khartoum in Sudan and Egypt.

East Africa’s Lake Plateau region is the source of many of the lakes and headstreams that supply the White Nile. It is widely accepted that the Nile has multiple sources.

As the Kagera River flows from Burundi’s highlands into Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria, it may be regarded as the longest headstream. As a result of its enormous size and shallow depth, Lake Victoria—the second-largest freshwater lake on Earth—is the source of the Nile.

Since the completion of the Owen Falls Dam (now the Nalubaale Dam) in 1954, the Nile has flowed northward over Ripon Falls, which has been submerged.

The Victoria Nile, a tributary of the river that runs over the Murchison (Kabalega) Falls and into the northern portion of Lake Albert, emerges in a westerly direction from the little Lake Kyoga (Kioga). Unlike Lake Victoria, Lake Albert is deep, narrow, and mountainous in nature. It also has a mountainous shoreline. In comparison to the other segments, the Albert Nile one is longer and moves more slowly.

The White Nile system in Bahr El Arab and the White Nile Rifts was a closed lake before the Victoria Nile merged with the main system around 12,500 years ago during the African humid period.

Luxor, Egypt’s Nile River irrigation system, can be seen in this aerial photo. The Greek historian Herodotus asserted that Egypt received a felucca from the Nile near Aswan. A never-ending supply of food was critical to the advancement of Egyptian civilization.

Fertile soil was left behind when the river overflowed its banks, and fresh layers of silt were deposited on top of the previous ones. An area that is navigable for steamers develops where the Victoria Nile and the lake’s waters meet.

At Nimule, where it enters South Sudan, the Nile is referred to as the Al-Jabal River, or Mountain Nile. From there, Juba is located approximately 200 kilometres (or about 120 miles) away.

This section of the river, which receives additional water from short tributaries on both banks, flows through a number of narrow gorges and through a number of rapids, including the Fula (Fola) Rapids. However, it is not navigable for commercial purposes.

The Fula (Fola) Rapids are among the most dangerous rapids on this section of the river. The primary channel of the river cuts through the centre of a large clay plain that is relatively flat and extends through a valley that is surrounded on either side by hilly terrain.

Both sides of the valley are bounded by the river itself. This valley can be found in the vicinity of Juba at an elevation that ranges from 370 to 460 metres (1,200 to 1,500 feet) above mean sea level.

Due to the fact that the gradient of the Nile there is only 1: 13,000, the large volume of additional water that arrives during the rainy season cannot be accommodated by the river, and as a consequence, during those months, practically the entire plain becomes inundated.

The Nile there has only a gradient of 1:33,000 in that section. Because of these factors, a significant amount of aquatic vegetation, including tall grasses and sedges (especially papyrus), are given the opportunity to flourish and expand their populations, which in turn allows for a greater variety of aquatic vegetation to exist.

Al-Sudd is the name given to this area, and the word sudd, which can be used to refer to both the region and the vegetation that can be found there, literally means “barrier.” The mild movement of the water promotes the growth of enormous swaths of plants, which eventually break off and float downstream.

This has the effect of clogging the primary stream and obstructing the channels that can be navigated. Since the 1950s, the South American water hyacinth has rapidly spread throughout the world, further obstructing canals as a result of its rapid proliferation as a result of its rapid proliferation.

The runoff water from a great number of other streams also flows into this basin. The Al-Ghazl (Gazelle) River receives water from the western part of South Sudan. This water is contributed to the river by the western part of South Sudan merging with the river at Lake No. Lake No. is a sizeable lagoon that is located at the point where the primary stream swings to the east.

Only a small portion of the water that flows through the Al-water Ghazl ever makes its way to the Nile because a significant amount of water is lost to evaporation along the way.

When the Sobat, which is also known as the Baro in Ethiopia, flows into the main stream of the river a short distance above Malakal, the river is referred to as the White Nile from that point on. The Sobat is also known as the Baro in Ethiopia.

The flow pattern of the Sobat is very different from that of the Al-Jabal, and it reaches its peak between the months of July and December. This peak occurs between the months of July and December. The amount of water that is lost each year as a result of evaporation in the Al-Sudd marshes is roughly equivalent to the annual flow of this river.

The length of the White Nile is approximately 800 kilometres (500 miles), and it is responsible for approximately 15% of the total volume of water that is carried by the Nile River down into Lake Nasser (also referred to as Lake Nubia in Sudan).

There are no significant tributaries that flow into it between Malakal and Khartoum, which is where it meets the Blue Nile. The White Nile is a large river that flows in a calm manner and is characterised by having a thin rim of marsh along its stretch rather frequently.

The shallowness and breadth of the valley are two factors that easily contribute to the amount of water that is lost. The impressive Ethiopian Plateau rises to a height of nearly 6,000 feet above sea level before dropping in a north-northwesterly direction. This is due to the fact that the source of the Blue Nile is found in Ethiopia.

The Ethiopian Orthodox Church reveres the spring because it is believed to be the spring’s source. The church also reveres the spring itself. This spring is the source of an aby, which is a small stream that eventually empties into Lake Tana. Lake Tana is 1,400 square miles in size and has a moderate depth.

After navigating a number of rapids and a deep valley on its way out of Lake Tana, the Abay eventually turns to the southeast and flows away from the lake. Although the lake is responsible for approximately 7 percent of the river’s flow, the silt-free water more than makes up for this factor.

The western and northwest regions of Sudan are traversed by the river as it makes its way to where it will eventually join the White Nile. It travels through a canyon that is approximately 4,000 feet lower than the normal elevation of the plateau as it makes its way from Lake Tana to the plains of Sudan.

Deep ravines are utilised by each and every one of its tributaries. The monsoon rain that falls on the Ethiopian Plateau and the rapid runoff from its numerous tributaries, which historically contributed the most to the annual Nile floods in Egypt, are what cause the flood season, which lasts from the end of July to the beginning of October.

The White Nile in Khartoum is a river that has a volume that is almost always the same. Over 300 kilometres (190 miles) to the north of Khartoum is where the last of the Nile’s tributaries, the Atbara River, flows into the Nile.

It reaches its peak between a height of 6,000 and 10,000 feet above mean sea level, close to Gonder and Lake Tana. Tekez, which means “Terrible” in Amharic and is known as Nahr Satt in Arabic, and Angereb, which is known as Baar Al-Salam in Arabic, are the two most important tributaries of the Atbara River.

The Tekez has a basin that is significantly larger than that of the Atbara, making it the most significant of these rivers. Before it combines with the Atbara River in Sudan, it travels through a breathtaking gorge located to the north of the country.

The Atbara River travels through Sudan at a level that is significantly lower than the average elevation of the plains for the majority of its route. When rainwater runs off of the plains, it causes gullies to form in the land that lies between the plains and the river. These gullies erode and cut into the land.

Similar to the Blue Nile in Egypt, the Atbara River goes through strong surges and ebbs of water. During the wet season, there is a sizable river, but during the dry season, the area is characterised by a series of pools.

More than ten percent of the Nile’s annual flow comes from the Atbara River, but almost all of it happens between July and October. There are two distinct sections that can be broken up into the United Nile, which is the section of the Nile that is located north of Khartoum.

The first 830 miles of the river are located in a desert region that receives very little precipitation and has very little irrigation along its banks. This region is located between Khartoum and Lake Nasser. The second section includes Lake Nasser, which serves as a reservoir for the water that is produced by the Aswan High Dam.

Additionally, included in this section is the irrigated Nile valley as well as the delta. About 80 kilometres (50 miles) to the north of Khartoum is where you’ll find Sablkah, also known as Sababka, which is the site of the sixth and highest cataract on the Nile.

There is a river that winds its way through the hills for a distance of eight kilometres. The river travels in a direction toward the southwest for approximately 170 kilometres, beginning at Abamad and ending at Krt and Al-Dabbah (Debba). The fourth cataract can be found in the middle of this stretch of river.

At the Dongola end of this bend, the river resumes its route heading north and then flows into Lake Nasser after going over the third waterfall. The eight hundred miles that separate the sixth cataract and Lake Naser are split up into stretches of calm water and rapids.

There are five well-known cataracts on the Nile as a result of crystalline rock outcroppings that cross the river. Even though there are sections of the river that are navigable around the waterfalls, the river as a whole is not completely navigable because of the waterfalls.

Lake Nasser is the second largest artificial body of water in the world, and it has the potential to cover an area that is up to 2,600 square miles in size. This includes the second cataract that can be found close to the border between Egypt and Sudan.

The section of rapids that is now the first cataract below the large dam was once a section of rapids that impeded the flow of the river. These rapids are now strewn with rocks.

From the first cataract all the way up to Cairo, the Nile flows northward through a narrow gorge with a flat bottom and a winding pattern that is generally carved into the limestone plateau that lies beneath it.

This gorge has a width of 10 to 14 miles and is surrounded on all sides by scarps that reach heights of up to 1,500 feet above the level of the river.

The majority of the cultivated land is located on the left bank because the Nile has a strong propensity to follow the eastern border of the valley floor for the last 200 miles of its journey to Cairo. This causes the Nile to follow the eastern border of the valley floor.

The mouth of the Nile is located in the delta, which is a low, triangular plain to the north of Cairo. A century after the Greek explorer Strabo discovered the division of the Nile into delta distributaries, the Egyptians began to construct the first pyramids.

The river has been channelled and redirected, and it now flows into the Mediterranean Sea by way of two significant tributaries: the Damietta (Dumy) and Rosetta branches.

The Nile delta, considered to be the prototypical example of a delta, was formed when sediment transported from the Ethiopian Plateau was used to fill in an area that had previously been a bay in the Mediterranean Sea. Silt makes up the majority of Africa’s soil, and its thickness can reach heights of up to 240 metres.

Between Alexandria and Port Said, it covers an area that is more than twice as large as Upper Egypt’s Nile Valley and stretches in a direction that is 100 miles north to south and 155 miles east to west. A gentle slope leads from Cairo down to the surface of the water, which is 52 feet below that point.

Lake Marout, Lake Edku, Lake Burullus, and Lake Manzala (Buayrat Mary, Buayrat Idk, and Buayrat Al-Burullus) are just a few of the salt marshes and brackish lagoons that can be found along the coast in the north. Other examples include Lake Burullus and Lake Manzala (Buayrat Al-Manzilah).

The changing climate and the availability of water resources. There are only a few locations in the Nile basin that have climates that can be classified as either completely tropical or truly Mediterranean.

The highlands of Ethiopia get more than 60 inches (1,520 millimetres) of rainfall during the northern summer, in contrast to the dry conditions that prevail in Sudan and Egypt during the northern winter.

It is often dry there because a large portion of the basin is subjected to the influence of northeast trade winds between the months of October and May. Southwest Ethiopia and areas of the East African Lakes region both have tropical climates with very even distributions of rainfall.

Depending on where in the lake region you are and how high you are, the average temperature throughout the year can fluctuate anywhere from 16 to 27 degrees Celsius (60 to 80 degrees Fahrenheit) in this area.

Humidity and Temperature

The relative humidity tends to hover around 80 percent on average, despite the fact that it varies quite a bit. The weather patterns in the western and southern regions of South Sudan are quite similar. These regions receive up to 50 inches of rain over the course of nine months (March to November), with the majority of this rainfall occurring in the month of August.

The relative humidity is at its lowest point between the months of January and March, while it is at its maximum point during the height of the rainy season. The months of July and August have the least amount of precipitation and, therefore, the highest average temperatures (December to February).

Unexplored Territories. Where exactly might one locate a polynya? Which body of water did the ancient city of Troy call home during its heyday? By going through the data, you may determine which bodies of water throughout the world have the highest temperatures, the shortest lengths, and the longest lengths.

As you travel further north, both the average amount of rainfall and the duration of the seasons will decrease. In contrast to the rest of the south, where the rainy season lasts from April all the way through October, south-central Sudan only experiences rain during the months of July and August.

A warm and dry winter from December through February is followed by a hot and dry summer from March through June, which is then followed by a warm and rainy summer from July through October. The warmest months in Khartoum are May and June, when the average temperature is 105 degrees Fahrenheit (41 degrees Celsius). January is the coolest month in Khartoum.

Al-Jazrah, which is located between the White and Blue Niles, receives just around 10 inches of rain on average each year, but Dakar, which is located in Senegal, receives more than 21 inches.

Because it receives fewer than five inches of rain on average each year, the area to the north of Khartoum is not suited for living there permanently. Strong gusts of wind known as squalls are responsible for transporting vast quantities of sand and dust to Sudan during the months of June and July.

Haboobs are storms that typically last between three and four hours in duration. Conditions resembling a desert can be found in the remaining areas that are located north of the Mediterranean.

Aridity, a dry climate, and a large seasonal and diurnal temperature range are some of the distinguishing features of the Egyptian desert and the northern part of Sudan. As an illustration, during the month of June, the highest daily average temperature in Aswan is 117 degrees Fahrenheit (47 degrees Celsius).

The mercury consistently climbs higher than the threshold at which water freezes (40 degrees Celsius). In the winter, average temperatures tend to be lower further north. During the months of November through March, Egypt experiences a season that can only be accurately referred to as “winter.”

The hottest season in Cairo is summer, with average high temperatures in the 70s and average low temperatures in the 40s. The rain that falls in Egypt originates mostly in the Mediterranean Sea, and it often falls during the winter months.

A little more than an inch in Cairo and less than an inch in Upper Egypt after it gradually decreased from eight inches along the shore.

When depressions from the Sahara or the coast move eastward in the spring, between the months of March and June, this can lead to a phenomenon known as khamsin, which is characterised by the presence of dry southerly winds.

When there are sandstorms or dust storms that cause the sky to become hazy, a phenomenon known as the “blue sun” can be seen for three or four days. The enigma surrounding the periodic ascent of the Nile remained unsolved until it was discovered that tropical regions played a role in the process of regulating it.

Nilometers, which are gauges made of natural rocks or stone walls with graded scales, were used by the ancient Egyptians to keep track of river levels. However, the precise hydrology of the Nile was not fully understood until the 20th century.

On the other hand, there is no other river in the world of comparable size that has a known regime as well. On a regular basis, the discharge of the main stream is measured, in addition to the discharge of its tributaries.

The Flooding Season

The heavy tropical rainfall that Ethiopia receives causes the Nile to swell throughout the summer, which in turn leads to an increase in the number of floods. The flooding in South Sudan begins in April, but the effects of the flooding aren’t seen in the nearby city of Aswan, Egypt, until July.

The water level is starting to climb at this moment, and it will continue to do so during the months of August and September, reaching its highest height in the middle of September. The highest temperature of the month in Cairo will now occur in the month of October.

The months of November and December mark the beginning of a rapid decline in the river’s level. The water level in the river is at its lowest point of the year right about now.

In spite of the fact that the flood takes place on a regular basis, both its severity and its timing are subject to change. Before the river could be controlled, years of high or low floods, particularly a sequence of such years, caused agricultural failure, which led to poverty and illness. This occurred before the river could be regulated.

If you follow the Nile upstream from its source, you may be able to get an estimate of how much the several lakes and tributaries contributed to the flood. Lake Victoria is the first large natural reservoir that is a part of the system.

In spite of the considerable rainfall that occurs around the lake, the lake’s surface evaporates almost as much water as it receives, and the majority of the lake’s annual outflow of 812 billion cubic feet (23 billion cubic metres) is caused by rivers that drain into it, most notably the Kagera.

This water originates in Lake Kyoga and Lake Albert, two lakes in which very little water is lost, and is transported by the Victoria Nile. Rainfall and the flow of other, smaller streams, particularly the Semliki, more than make up for the amount of water that is lost to evaporation.

As a consequence of this, Lake Albert is responsible for delivering 918 billion cubic feet of water annually to the Al-Jabal River. In addition to this, it obtains a considerable amount of water from the tributaries that are fed by the Al-rushing Jabal.

The large marshes and lagoons in the Al-Sudd region are the primary cause of the substantial fluctuations in the level of the Al-discharge Jabal. Even though seepage and evaporation have removed over half of the water, a river that flows downstream from Malakal and is known as the Sobat River, has almost completely compensated for the loss.

The White Nile provides a dependable source of fresh water throughout the entire calendar year. More than eighty percent of the water that is available comes from the White Nile during the months of April and May, when the main stream is at its lowest level.

It obtains roughly the same quantity of water from each of its two sources, which are distinct. The first source is the amount of rain that fell during the summer on the East African Plateau in the year before.

The Sobat receives its water from a variety of sources, including the headstreams of the Baro and the Pibor, as well as the Sobat, which feeds into the main stream about downstream from Al-Sudd.

Significant shifts in the water level of the White Nile are brought on by the annual flooding of the Sobat River in Ethiopia.

The rains that fill the river’s upper basin begin in April, but they don’t arrive in the lower levels of the river until late November or December. This causes significant flooding across the 200 miles of plains that the river travels through since it delays the rains.

The flood that is caused by the Sobat river almost never deposits any of its muck into the White Nile. The Blue Nile, the largest and most significant of the three primary affluents that originate in Ethiopia, is primarily responsible for the arrival of the Nile flood in Egypt.

In Sudan, two of the river’s tributaries that originated in Ethiopia, the Rahad and the Dinder, are celebrated with open arms. Because it joins the main river so much more quickly than the White Nile does, the flow pattern of the Blue Nile is more unpredictable than that of the White Nile.

Beginning in June, the level of the river begins to rise, and it continues to do so until the first week of September, when it reaches its highest point in Khartoum. Both the Blue Nile and the Atbara River get their water supply from the rain that falls on Ethiopia’s northern Plateau.

In contrast, the Blue Nile continues to flow throughout the year despite the fact that the Atbara transforms into a chain of lakes during the dry season, as was mentioned earlier. The Blue Nile surges in May, bringing with it the first flooding to central Sudan.

The peak occurs in August, following which the level again starts to drop. The rise frequently exceeds 20 feet in Khartoum. The White Nile becomes a sizeable lake and is delayed in its flow when the Blue Nile is flooded because it holds back water from the White Nile.

The south of Khartoum-located Jabal al-Awliy Dam exacerbates this ponding effect. The flood reaches its height and enters Lake Nasser when the average daily inflow from the Nile increases to around 25.1 billion cubic feet in late July or early August.

This sum is sourced from the Blue Nile in excess of 70%, the Atbara in excess of 20%, and the White Nile in excess of 10%. The inflow is at its lowest point in early May. The White Nile is principally responsible for the 1.6 billion cubic feet of discharge per day, with the Blue Nile accounting for the remainder.

Normally, Lake Nasser receives 15% of its water from the East African Lake Plateau system, with the remaining 85% coming from the Ethiopian Plateau. Storage space in the reservoir of Lake Nasser ranges from more than 40 cubic miles (168 cubic kilometres) to more than 40 cubic miles (168 cubic kilometres).

When Lake Nasser is at its maximum capacity, there is an annual loss of up to ten percent of the lake’s volume due to evaporation. However, this loss drops to around one-third of its maximum level when the lake is at its minimum level.

Life on Earth includes both animals and plants. Depending on the amount of rainfall in a location without irrigation, there may be different plant life zones. Southwest Ethiopia, the Plateau of Lake Victoria, and the Nile-Congo border are all covered with tropical rainforest.

Heat and ample rainfall produce dense tropical forests, including ebony, banana, rubber, bamboo, and coffee shrubs. Most of the Lake Plateau, Ethiopian Plateau, Al-Ruayri, and the southern Al-Ghazl River region have savanna, which is distinguished by the sparse growth of medium-sized trees with thin foliage and a ground covering of grass and perennial herbs.

Nile Herbs and Grass

This type of savanna can also be found along the Blue Nile’s southern border. The lowlands of Sudan are home to a diverse ecosystem that includes open grassland, trees with prickly branches, and sparse vegetation. South Sudan’s vast central region, which covers an area of more than 100,000 square miles during the rainy season, is particularly prone to flooding.

Long grasses that mimic bamboo, such as reed mace ambatch (turor), and water lettuce (convolvulus), as well as the South American water hyacinth (convolvulus), can be found there. A stretch of orchard shrub country and thorny savanna can be found to the north of a latitude of 10 degrees north.

After a rain, grass and herbs can be found in this area’s small tree stands. However, in the north, rainfall decreases and vegetation thins out, leaving just a few patches of thorny bushes, usually acacias, remaining.

Since Khartoum, it has been a true desert, with very little to no regular rainfall and only a few stunted shrubs remaining as evidence of its previous existence. In the aftermath of a downpour, drainage lines may be covered with grass and small herbs, but these are rapidly swept away.

The Wildlife of the Nile

In Egypt, the vast majority of the vegetation along the Nile River is the result of agriculture and irrigation. The Nile River system is home to a variety of fish species. In the lower Nile system, fish such as the Nile perch, which may weigh up to 175 pounds, the bolti, barbel, and a variety of cats like the elephant-snout fish and the tigerfish, or water leopard, can be found.

Lungfish, mudfish, and the sardine-like Haplochromis can all be found upstream in Lake Victoria, along with the majority of these species. While the spiny eel can be found in Lake Victoria, the common eel can be found as far south as Khartoum.

The majority of the Nile River is home to Nile crocodiles, but they have yet to spread to the upper Nile basin lakes. More than 30 species of venomous snakes can be found in the Nile basin, including a soft-shelled turtle and three species of monitor lizards.

The hippopotamus, which used to be widespread across the Nile system, may now only be found in the Al-Sudd region and other locations further to the south. Fish populations in Egypt’s Nile River have reduced or disappeared totally after the construction of the Aswan High Dam.

Water levels in Lake Nasser have dropped precipitously due to a halt in the migration of numerous Nile fish species. The dam has led to a significant reduction in the amount of waterborne nitrogen runoff, which has been linked to the anchovy population decline in the eastern Mediterranean.

The Nile perch, which has been turned into a commercial fishery for the Nile perch and other species, is thriving. People:

The three regions that the Nile passes through are the delta of the Nile, which is inhabited by Bantu-speaking people; the Bantu-speaking groups that are located around Lake Victoria; and the Saharan Arabs.

Many of these people’s ecological links to this waterway reflect their wide range of language and cultural backgrounds. People from the Nilotic-speaking ethnic groups of Shilluk, Dinka, and Nuer live in the South Sudanese state.

The Shilluk people are farmers who live in sedentary communities thanks to the Nile’s ability to irrigate their land. The Dinka and Nuer pastoralist movements are affected by the Nile’s seasonal flow.

During the dry season, they relocate their herds away from the river’s banks, while during the wet season, they return to the river with their herds. People and rivers have such a close relationship nowhere else but on the Nile floodplain.

The Nile and Farmers

The agricultural floodplain south of the delta has a population density of almost 3,320 people per square mile on average (1,280 per square kilometre). Peasant farmers (fellahin) make up the majority of the population, which means they must conserve water and land in order to maintain their size.

Prior to the construction of the Aswan High Dam, a sizeable quantity of silt originated in Ethiopia and was carried down from the country’s highlands. The fertility of the riverine soils remained preserved despite significant agriculture throughout time.

People in Egypt paid close attention to river flow since it was an indicator of future food shortages and, conversely, it was a predictor of excellent harvests. Economy.irrigations Almost certainly, irrigation was developed in Egypt as a means of cultivating crops.

Because of the land’s five-inch-per-mile slope from south to north and the slightly steeper slope from the riverbanks to the desert on either side, irrigation from the Nile is a practical option.

The Nile was initially utilised in Egypt as an irrigation system when seedlings were sown in the mud that was left behind after the annual floodwaters had receded. This was the beginning of the Nile’s long history of agricultural use.

It took many years of experimentation and refinement before basin irrigation became a widely used method. Large basins as large as 50,000 acres were created using earth barriers to separate the flat floodplain into manageable sections (20,000 hectares).

All of the basins were inundated by the yearly Nile flood that occurred this year. The basins had been left unattended for as long as six weeks. As the river level receded, it left behind a thin coating of rich Nile silt. Autumn and winter crops were planted in the soggy soil.

Farmers were always at the mercy of the flood’s unexpected nature due to the fact that they were only able to cultivate a single crop on an annual basis as a result of the system’s regular changes in the magnitude of the flood.

Such ancient systems as the shaduf (a counterbalanced lever device that uses a long pole), the Persian waterwheel, or the Archimedes screw, allowed for some perennial irrigation along the riverbanks and on areas above flood level, even in times of flood. Modern mechanical pumps are beginning to replace this manually or animal-powered equipment.

The basin method of irrigation has largely been replaced by the perennial irrigation system, in which the water is controlled so that it can run into the soil at regular intervals throughout the year. This allows water to be absorbed more effectively by the plant roots.

Perennial irrigation was made possible thanks to a number of barrages and waterworks built before the turn of the nineteenth century. By the beginning of the 20th century, the canal system had been improved and the first dam at Aswn had been constructed (see below Dams and reservoirs).

Since the construction of the Aswan High Dam was finished, nearly all of Upper Egypt’s land that was once irrigated by basins has been converted to receive permanent irrigation.

There is some rainfall in Sudan’s southern regions, so the country’s reliance on the Nile is not absolute. Because the surface is more uneven, there is less silt deposition, and the area inundated fluctuates each year, basin irrigation from the Nile floods is less successful in these places.

Since the 1950s, diesel-powered pumping systems have made a significant dent in the market share of traditional irrigation techniques that relied on either the White Nile or the main Nile in the Khartoum region. Dams and reservoirs are two types of water storage facilities.

Diversion dams were built across the Nile at the delta head 12 miles downstream of Cairo in order to raise the water level upstream to supply irrigation canals and manage navigation.

The modern irrigation system in the Nile Valley may have been inspired by the delta barrage design, which was finished in 1861 and later enlarged and improved upon. This is because both systems were completed at about the same time.

The Zifta Barrage, which is located about halfway up the Damietta branch of the deltaic Nile, was added to this system in 1901. The Asy Barrage was completed in 1902, over 200 kilometres upstream of Cairo.

As a direct consequence of this, construction began in 1930 on the barrages at Isn (Esna), located around 160 miles above Asy, and Naj Hammd, located approximately 150 miles above Asy.

The first dam at Aswn was erected between 1899 and 1902, and it features four locks to make transportation easier. During the years 1908–1911 and 1929–1934, the dam was expanded twice in order to raise the water level and enhance its capacity.

In addition to that, there is a hydroelectric power plant on the premises that can generate 345 megawatts. At 4 miles upstream of the Aswan High Dam, which is around 600 miles from Cairo, lies the first Aswan dam. It was built next to a river with granite banks that was 1,800 feet wide.

The flow of the Nile can be controlled by dams, which will increase agricultural production, generate hydroelectric power, and rescue populations and crops further downstream from unprecedented levels of flooding.

Beginning in 1959, construction on the project was finished in 1970. At its highest point, the Aswan High Dam rises 364 feet above the riverbed, measuring 12,562 feet long and 3,280 feet broad. The capacity of power generation that has been installed is 2,100 megawatts. The length of Lake Nasser extends 125 kilometres into Sudan from the dam site.

For Egypt’s sake and that of Sudan’s, the Aswan High Dam was built with the primary purpose of storing enough water in the reservoir to protect Egypt from the dangers of a series of years with Nile floods that are above or below the long-term normal. Because of a bilateral agreement that was struck in the year 1959, Egypt is entitled to a larger portion of the yearly borrowing limit that is divided into three equal parts.

In order to manage and distribute water in accordance with the expected worst possible sequence of flood and drought events over a period of 100 years, one-fourth of Lake Nasser’s entire storage capacity is set aside as relief storage for the biggest anticipated flood during such a time (called “century storage”).

Aswan’s High Dam is a landmark. Egypt is home to the impressive Aswan High Dam. In the years leading up to and following its completion, the Aswan High Dam has generated a great deal of controversy. Opponents claim that the dam’s construction has reduced the Nile’s total flow, causing saltwater from the Mediterranean Sea to overflow the river’s lower reaches, resulting in salt deposition on the delta’s soils.

Those who are against the construction of a hydroelectric dam have also made the assertion that the downstream barrages and bridge structures have developed cracks as a result of erosion and that the loss of silt has resulted in coastal erosion in the delta.

To date, fish populations in the delta’s vicinity have suffered significantly due to the removal of this valuable source of nutrients. Advocates of the project claim that these negative consequences are worth the assurance of constant water and power supplies because Egypt would’ve faced a severe water crisis from 1984 to 1988.

When there is not enough water in the Blue Nile, the Sennar Dam on the Blue Nile releases water that is used to irrigate the Al-Jazrah plain in Sudan. It can also be used to generate hydroelectric power.

Second, the Jabal al-Awliy dam was completed in 1937; its objective wasn’t to provide irrigation water for Sudan, but rather it was created so that Egypt would have more water at its disposal when it was in need (January to June).

Additional dams, such as the Al-Ruayri Dam on the Blue Nile, which was finished in 1966, and one on the Atbara at Khashm al-Qirbah, which was finished in 1964, have made it possible for Sudan to use all of the water that is allotted to it from Lake Nasser.

Sennar Dam on Sudan’s Blue Nile River

The Sennar Dam on Sudan’s Blue Nile River is one example. Tor Eriksson, also known as Black Star. In 2011, Ethiopia began construction on the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD). A dam of roughly 5,840 feet long and 475 feet high was planned in the western part of the country, near the border with Sudan.

A hydroelectric power plant was going to be built so that it could generate 6,000 megawatts of electricity. In order to begin construction on the dam, the course of the Blue Nile was altered in 2013. Protests were sparked by fears that the project would have a severe impact on the water supplies farther downstream (especially in Sudan and Egypt).

The Dam of the Ethiopian Renaissance, also known as the Grand Ethiopian Dam, Construction began in 2013 on the Ethiopian Renaissance Dam that will be located on the Blue Nile. Jiro Ose has reworked the original.

The Owen Falls Dam, which is now known as the Nalubaale Dam, was finally finished in 1954 and transformed Lake Victoria in Uganda into a reservoir. It is situated on the Victoria Nile just a short distance beyond the point where the waters of the lake enter the river.

When there are big floods, surplus water can be stored to compensate for a lack of water in years with low water levels. A hydroelectric plant generates electricity for Ugandan and Kenyan industries by harnessing the lake’s fall.

Navigation

When roads are impassable due to flooding, the Nile River serves as a vital transportation artery for people and commodities alike. River steamers remain the only mode of transportation in the bulk of the region, notably in South Sudan and Sudan south of latitude 15° N, where vehicle mobility is often unfeasible from May to November.

In Egypt, Sudan, and South Sudan, it is not unusual for towns to be constructed along rivers. The Nile and its tributaries are navigable by steamers for 2,400 kilometres across Sudan and South Sudan.

Until 1962, the only way to travel between Sudan’s northern and southern areas, today known as Sudan and South Sudan, was by stern-wheel river steamers with a shallow draught. The cities of Kst and Juba are the most important stops along this route.

During the high water season, the Dongola reaches of the main Nile, the Blue Nile, the Sobat, and the Al-Ghazal River all offer seasonal and supplementary services. The Blue Nile is navigable only during high water seasons and then only as far as Al-Ruayri.

Due to the existence of cataracts to the north of Khartoum, only three sections of the river in Sudan are capable of being navigated. One of these runs from the Egyptian border to the southern tip of Lake Nasser.

It is the second cataract that separates the third from the fourth cataract. The third and most important stretch of the road links the southern city of Khartoum in Sudan to the northern city of Juba, which is the capital of Sudan.

The Nile and its delta canals are crisscrossed by numerous small boats, and sailing boats and shallow-draft river steamers can cruise as far south as Aswan. The Nile River- Before it empties into the Mediterranean Sea, the Nile River travels a distance of more than 6,600 kilometres (4,100 miles).

For thousands of years, the river has provided an irrigation source for the dry country around it, transforming it into fertile farmland. In addition to providing irrigation, the river serves as a vital waterway for commerce and transportation today.

Repeating the Story of the Nile

The Nile is the world’s longest river and the “father of all African rivers,” according to some accounts. The Nile is known in Arabic as Bar Al-Nil or Nahr Al-Nil. It rises south of the equator, flows through northern Africa, and empties into the Mediterranean Sea.

It has a length of about 4,132 miles (6,650 kilometres) and drains an area of about 1,293,000 miles (2,349,000 square kilometres). Its basin encompasses all of Tanzania; Burundi; Rwanda; the Democratic Republic of the Congo; Kenya; Uganda; South Sudan; Ethiopia; Sudan; and the cultivated area of Egypt.

Its furthest point of origin is the Kagera River in Burundi. The three principal streams that make up the Nile are the Blue Nile (Arabic: Al-Bar Al-Azraq; Amharic: Abay), the Atbara (Arabic: Nahr Abarah), and the White Nile (Arabic: Al-Bar Al-Abyad), whose headstreams drain into Lakes Victoria and Albert.

The Semitic root naal, which refers to a valley or a river valley and, later, by extension of the meaning, a river, is the source of the Greek term Neilos (Latin: Nilus).

The Ancient Egyptians and Greeks had no understanding of why, in contrast to other significant rivers they were aware of, the Nile flowed from the south to the north and was in flood during the warmest season of the year.

The ancient Egyptians called the river Ar or Aur (Coptic: Iaro) “Black” because of the hue of the sediments it brought during floods. The earliest names for the region are Kem or Kemi, which both stem from Nile mud and indicate “black” and denote darkness.

In the Greek poet Homer’s epic poem The Odyssey (7th century BCE), Aigyptos is the name of both the kingdom of Egypt (feminine) and the Nile (masculine) that it flows through. The Egyptian and Sudanese names for the Nile are currently Al-Nil, Bar Al-Nil, and Nahr Al-Nil.

Some of the world’s most advanced civilizations once flourished in the Nile River region, which occupies one tenth of Africa’s total territory but has since been abandoned by the vast majority of its inhabitants.

Primitive farming techniques and the use of the plough originated among those who lived near rivers. Rather vaguely defined watersheds separate the Nile Basin from Egypt’s Al-Jilf al-Kabr Plateau, Sudan’s Marrah Mountains, and the Congo Basin from the western side of the basin.

The basin’s eastern, eastern, and southern borders, respectively, are formed by geographic features such as the Red Sea Hills, the Ethiopian Plateau, and the East African Highlands, which are home to Lake Victoria, a lake that receives water from the Nile (part of the Sahara).

Farming along the Nile’s banks is possible all year long because of its year-round water supply and the region’s high temperatures. So, even in areas with enough yearly rainfall, farming without irrigation is often fraught with risk due to large annual changes in precipitation levels.

The Nile River is also extremely important for transportation, particularly during the wet season when driving a vehicle is difficult due to the increased risk of flooding.

However, since the start of the 20th century, advances in air, rail, and highway infrastructure have drastically diminished the need for the waterway. Scientists believe that the Nile’s source was between 18 and 20 degrees north latitude when it was a smaller stream 30 million years ago. This corresponds to a location in Africa.

Back then, the Atbara River may have been one of its principal tributaries. The vast enclosed drainage system, which is home to Lake Sudd, is located to the south.

According to one theory regarding the establishment of the Nile system, the East African drainage system that empties into Lake Victoria might have acquired a northern exit 25,000 years ago, allowing water to flow into Lake Sudd.

The Nile’s system has its beginnings here. Because of the overflow, the lake was drained and the water spilled to the north. The water level of this lake rose steadily over time due to the buildup of sediments.

The two principal branches of the Nile were connected by a riverbed that was formed by the overflow water from Lake Sudd. Thus, the Lake Victoria to Mediterranean Sea drainage system was brought under one umbrella.

The Nile delta comprises seven important locations in the modern-day basin of the modern-day Nile. They are Al Jabal (El Jebel), White Nile, Blue Nile, Atbara, the Nile north of Khartoum, Sudan; and the Nile delta.

The region of East Africa known as the Lake Plateau is the origin of a great number of the headstreams and lakes that eventually feed into the White Nile. Rather than coming from a single source, it is generally acknowledged that the Nile originates in several locations.

The Kagera River, which rises in Burundi’s highlands near Lake Tanganyika’s northern edge and empties into Lake Victoria, is frequently referred to as the “headstream” because of its location so far upstream.

The majority of the water that flows into the Nile originates in Lake Victoria, which is the second-largest freshwater lake in the world. Lake Victoria is a huge, shallow body of water with a surface area of nearly 26,800 square miles. Located in Jinja, Uganda, the Nile River begins its voyage on the northern shore of Lake Victoria.