7 Interesting Facts about Ancient Egyptian Language

Updated On: November 08, 2023 by Dina Essawy

We are all aware that Herodotus once remarked, “Egypt is the gift of the Nile,” but not everyone is aware of how true this statement is. Ancient Egypt’s civilization would not have persisted in the same way without the Nile. Agriculture was made secure by the consistent water supply and the regular floods that were predictable. Ancient Egyptians were not in danger like their neighbours in Mesopotamia, who were always concerned about the unpredictable and deadly floods that threatened their lands and way of life. Instead of reconstructing what had been destroyed by the floods as their neighbours did, the Egyptians spent their time establishing a sophisticated society and planning their harvesting according to the Nile calendar.

Creating a whole language was one of the Ancient Egyptians’ greatest accomplishments. Hieroglyphs, which are also known as holy carvings, date back to 3000 B.C. It is related to North African (Hamitic) languages like Berber and Asiatic (Semitic) languages like Arabic and Hebrew through sharing the Afro-Asiatic language family. It had a lifespan of four thousand years and was still in use in the eleventh century AD, making it the world’s longest continuously recorded language. Nevertheless, it altered during its existence. What academics refer to the language as Old Egyptian, which existed from 2600 BC to 2100 BC, was the precursor of Ancient Egyptian.

Although it was only spoken for around 500 years, Middle Egyptian, also known as Classical Egyptian, began approximately 2100 BC and remained the predominant written hieroglyphic language for the remainder of ancient Egypt’s history. Late Egyptians started to take the place of Middle Egyptian as a spoken language around 1600 BC. Although it was a downgrade from earlier phases, its grammar and parts of its lexicon had significantly changed. Demotics emerged during the Late Egyptian period, which lasted from around 650 BC to the fifth century AD. Coptic evolved from Demotic.

Contrary to popular misconception, the Coptic language is just an extension of ancient Egyptian, not a separate Biblical language that can stand on its own. Beginning in the first century AD, Coptic was spoken for probably another thousand years or more. Now, it only continues to be pronounced during a few services of the Egyptian Coptic Orthodox Church. Modern researchers have received some guidance on hieroglyphic pronunciation from Coptic. Sadly, Arabic is steadily displacing Coptic, endangering the survival of the last stage of the ancient Egyptian language. The syntax and vocabulary of the present colloquial Egyptian language share a significant amount with the Coptic language.

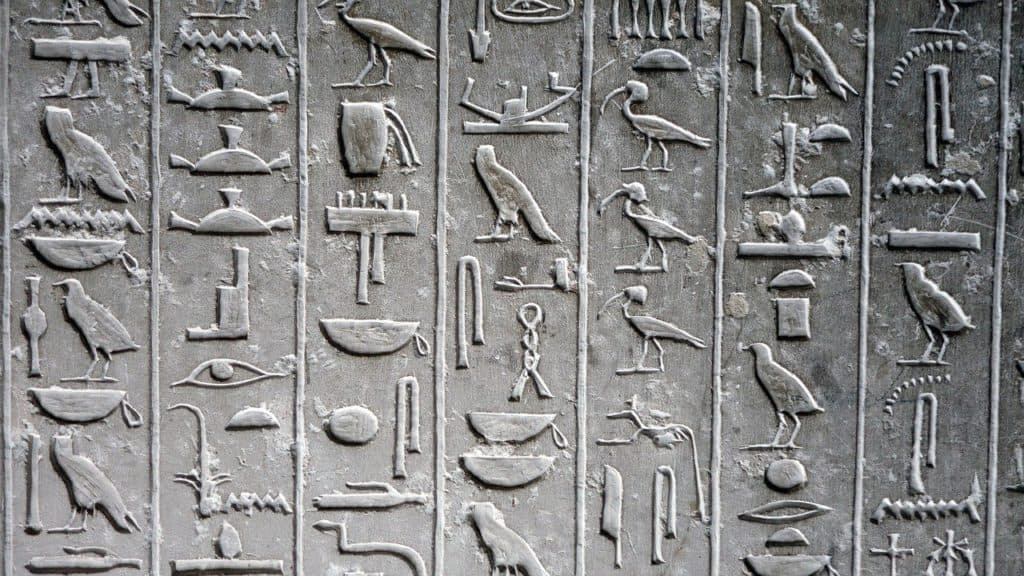

It’s not simple to understand Hieroglyphs, but after you get beyond the first uncertainty, it gets easier. Each sign does not always represent a single letter or sound; rather, it is frequently a trilateral or bilateral sign, denoting three letters or sounds. It can also represent a whole word. Usually, a determinative will be used in conjunction with words. The letters p and r are used to spell the word “house,” and then a drawing of a home is added as a determinative at the end of the word to make sure the reader understands what is being discussed.

1) The Invention of Hieroglyphs

The name Medu Netjer, which means “The Words of the Gods,” was given to the hieroglyphs of ancient Egypt. The more than 1,000 hieroglyphs that make up the hieroglyphic writing systems were thought to have been created by the gods. More precisely, the writing system was developed by the deity Thoth to improve Egyptian wisdom and memory. The first solar god thought it was a horrible idea to give humanity a writing system because he wanted them to think with their minds, not with writing. But Thoth still handed the Egyptian scribes their writing method.

Because they were the only people who could read Egyptian hieroglyphs, scribes were highly revered in ancient Egypt. When the pharaonic civilisation first emerged, just before 3100 B.C., the pictorial script was developed. 3500 years after their invention, in the fifth century A.D., Egypt produced its final hieroglyphic writing. And strangely, once the language was replaced with writing systems based on letters, it was impossible to understand the language for 1500 years. Early Egyptian hieroglyphs (pictographs) could not convey feelings, thoughts, or beliefs.

Furthermore, they were unable to articulate the past, present, or future. But by 3100 B.C., grammar, syntax, and vocabulary were all part of their language system. Additionally, they developed their writing skills by using a system of ideograms and phonograms. Phonograms represent the individual sounds that make up a given word. Phonograms, in contrast to pictographs, are incomprehensible to non-native speakers of the language. There were 24 of the most often used phonograms in Egyptian hieroglyphs. To further explain the meanings of words written out in phonograms, they added ideograms at the conclusion.

2) Scripts of the Ancient Egyptian Language

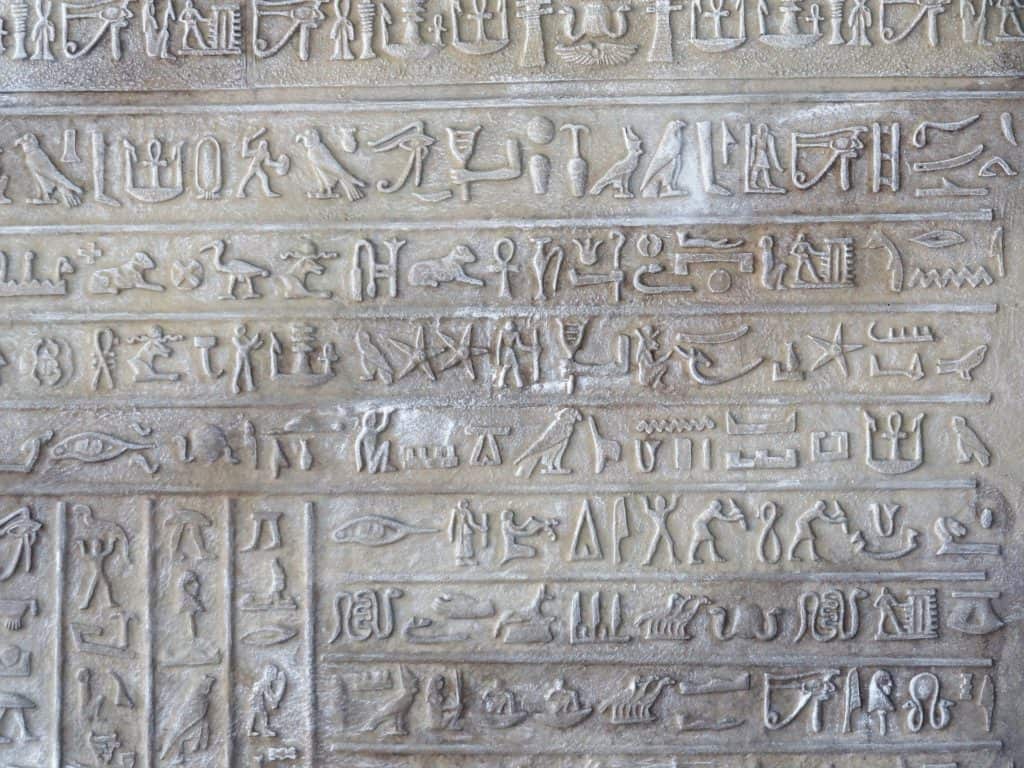

There were four distinct scripts used to write the ancient Egyptian language: hieroglyphs, hieratic, demotic, and Coptic. Over the extended time that the ancient Egyptian language was in use, these characters did not all arise at once but rather successively. It also demonstrates how mature the ancient Egyptians were in their thought, foreseeing that the complexity and advancement of life would need the creation of the appropriate methods of communication to enhance and document the increasingly extensive and advanced activities.

The earliest writing used in ancient Egypt was called hieroglyphics, and it is one of the most beautifully written scripts ever created. By the passage of time, the Egyptians were compelled to create a new, more cursive and straightforward script to accommodate their expanding demands and to meet administrative requirements; as a result, they created a cursive script known as Hieratic. Later phases required the Hieratic writing to be more cursive to accommodate the many affairs and social interactions. The demotic script was the name given to this novel kind of cursive.

The Coptic script was developed subsequently to accommodate the needs of the time. The Egyptian language was written using the Greek alphabet and seven characters from the Demotic scripts. It is appropriate to dispel a common misunderstanding about the ancient Egyptian language, which is called “the Hieroglyphic language” here. Writing in hieroglyphs is a script, not a language. There are four distinct scripts used to write the same ancient Egyptian language (Hieroglyphs, Hieratic, Demotic, Coptic).

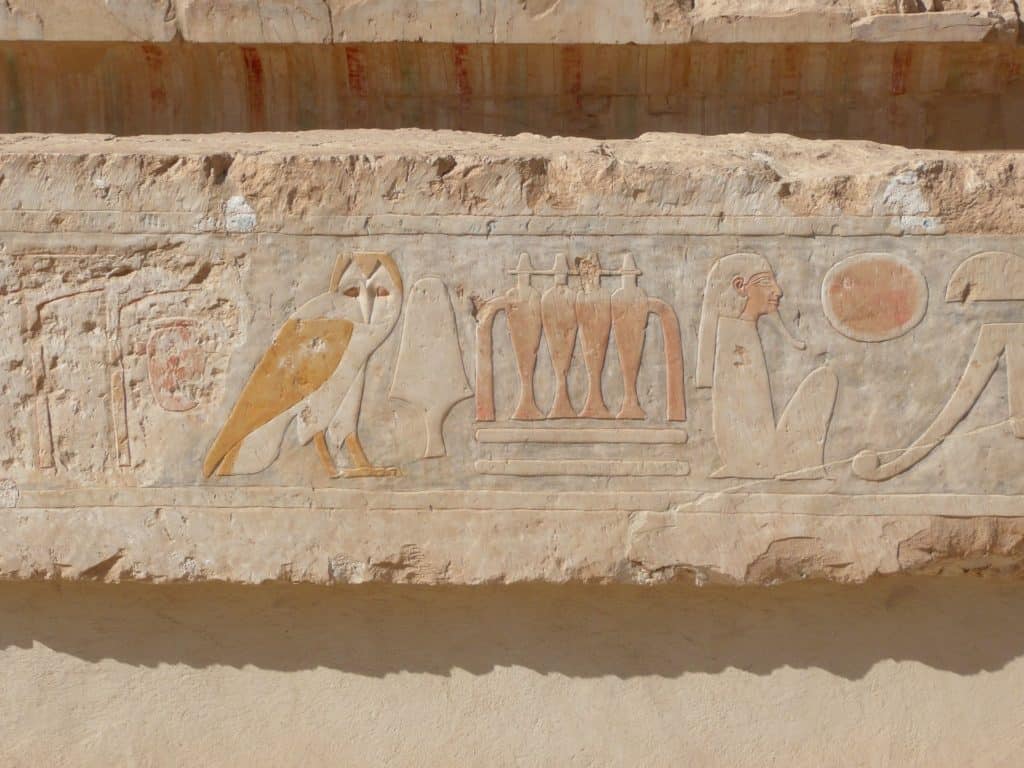

Hieroglyphic Script: The earliest writing system the ancient Egyptians employed to record their language was hieroglyphic. The terms hieros and glyphs in Greek are the sources of the phrase. They refer to its writing on the walls of holy locations like temples and tombs as “sacred inscriptions.” Temples, public monuments, tomb walls, stelae, and other artefacts of many types all had hieroglyphic lettering.

Hieratic: The term derives from the Greek adjective hieratikos, which means “priestly.” Because priests frequently utilised this script throughout the Greco-Roman era, it was given the nickname “priestly.” All older scripts that are sufficiently cursive to render the signs’ original graphic forms unrecognisable now go by this designation. The genesis of such a basic and cursive script was largely driven by the growing desire to communicate and document. Although much of it was written on papyrus and ostraca, there are occasionally Hieratic inscriptions found on stone as well.

Demotic: The word comes from the Greek word demotions, which means “popular.” The name does not imply that the script was produced by some members of the public; rather, it refers to the script’s widespread usage by all individuals. Demotic, a highly quick and straightforward variant of Hieratic writing, initially appeared about the eighth century BCE and was employed up until the fifth century CE. It was inscribed in Hieratic on papyrus, ostraca, and even on stone.

Coptic: The final stage of Egyptian writing evolution is represented by this script. The Greek word Aegyptus, which referred to the Egyptian language, is likely where the name Coptic originates. Vowels were introduced into Coptic for the first time. This may have been very useful in figuring out how to pronounce the Egyptian language properly. Greek letters were used to write ancient Egyptian as a political necessity after the Greek conquest of Egypt. The Greek alphabet was used to write the Egyptian language, along with seven Egyptian sign letters that were adapted from Demotic (to represent Egyptian sounds which did not appear in Greek).

3) Rosetta Stone Analyzation

The Rosetta Stone is a granodiorite stela engraved with the same inscription in three scripts: Demotic, Hieroglyphics, and Greek. To various individuals, it represents different things. The stone was discovered by French soldiers in the city of Rosetta (modern-day el Rashid) in July 1799 during Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt. East of Alexandria, close to the Mediterranean coast, was where Rosetta could be found.

Officer Pierre François Xavier Bouchard (1772–1832) discovered the sizable engraved stone piece when Napoleon’s troops were building fortifications. The importance of the juxtaposition of the hieroglyphic and Greek writings was instantly apparent to him, and he rightly assumed that each script was a translation of a single document. When the Greek instructions for how the stela’s content was to be published were translated, they confirmed this hunch: “This edict should be written on a stela of hard stone in holy (hieroglyphic), native (Demotic), and Greek letters.” As a result, the Rosetta Stone, or “the stone of Rosetta” in French, was given that name.

Over the last two centuries, many groups have adopted the Rosetta Stone’s kaleidoscopic symbolism, making it a worldwide icon since it was first discovered. The imperial aspirations of France and England in their fight to create, preserve, and expand colonial empires in the late 18th and early 19th centuries are reflected in the object’s present home in the British Museum. The writing painted on the stone’s sides reading “taken in Egypt by the British army 1801” and “given by King George III” shows that the stone itself still retains the scars of these battles.

Egypt, which was then a part of the Ottoman empire, was caught between opposing political forces. Egypt entered a century that was frequently exploited as a result of Napoleon’s invasion in 1798 and subsequent defeat by British and Ottoman armies in 1801. Mass demonstrations, widespread resistance, and intermittent uprisings were sparked by European powers’ repression of autonomous development and were usually organised around nationalist feelings among the inhabitants, which were predominately Islamic and Coptic. Following the Treaty of Alexandria, the stone was formally given to the British in 1801, and in 1802 it was deposited in the British Museum.

It has stayed nearly continuously shown there with the registration number BM EA 24. Understanding how many groups have influenced the meaning of the Rosetta Stone requires knowledge of its historical background.

The stone stood for both scientific advancement and political hegemony to the soldiers of Napoleon who discovered it and to the British soldiers who took possession of it after the French defeat. The stone has long served as a symbol of Egypt’s many ethnic groups’ common national and cultural history. Because of this, some people have viewed the “export” of the Rosetta Stone as a colonial “theft” that should be made up for by repatriation to the contemporary Egyptian state.

The phrase “Rosetta Stone” has become widely used to refer to anything that cracks codes or discloses secrets as a result of its crucial role in decoding ancient Egyptian inscriptions. The use of the name for a famous language-learning programme is the finest example of how the corporate world has rapidly tapped into its popularity. The term “Rosetta Stone” has become so commonplace in a 21st-century global culture that future generations could one day use it without realising that it refers to the accidental finding of an extraordinary-looking rock in Egypt.

The trilingual character of the text on the Rosetta Stone sparked a decipherment craze in Europe as scientists began serious attempts to comprehend the Egyptian letters with the aid of the Greek translation. The demotic inscription was the subject of the first substantial attempts toward decipherment since it was the best preserved of the Egyptian versions, despite popular imagination linking the Rosetta Stone most directly to the Egyptian hieroglyphic character.

French philologist Antoine Isaac Silvestre de Sacy (1758-1838) and his Swedish pupil Johan David Kerblad (1763-1819) were able to read human names, establish the phonetic values for many of the so-called “alphabetic” signs, and ascertain the translation for a few other words. These attempts began by attempting to match the sounds of the Egyptian letters to the personal names of the kings and queens stated in the Greek inscription.

The competition to read Egyptian hieroglyphs between Thomas Young (1773-1829) and Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) was made possible by these breakthroughs. They were both quite smart. Young, who was seventeen years older, made amazing progress with both the hieroglyphic and demotic scripts, but Champollion was the one who spearheaded the ultimate innovation.

Since he was young, Champollion had devoted his intellectual energy to studying ancient Egypt, studying Coptic under Silvestre de Sacy. Champollion used his knowledge of Coptic to properly determine the interpretation of the hieroglyphic writing of the word “to give birth,” proving the theory that Egyptian hieroglyphs conveyed phonetic sounds. He read Ramses’ and Thutmosis’ cartouches in their native language for the first time in well over a thousand years at this point. According to a tradition told by Champollion’s nephew, when Champollion realised the importance of this confirmation, he rushed into his brother’s office, exclaimed “I’ve got it!” and collapsed, passing out for nearly a week. With this remarkable achievement, Champollion cemented his status as the “father” of Egyptology and contributed to the development of a brand-new field of study.

Scholars were able to determine the Rosetta Stone had three translations of the same text when Champollion and his successors succeeded in unlocking the mysteries of the Egyptian script. That text’s contents were previously known from the Greek translation; it was an edict issued by Ptolemy V Epiphanes, the monarch. A synod of priests from all across Egypt met on March 27, 196 BCE, to commemorate Ptolemy V Epiphanes’ coronation the day before at Memphis, the nation’s traditional capital. Memphis was thereafter commercially overshadowed by Alexandria on the Mediterranean coast, but it nevertheless served as a significant symbolic link to the pharaonic past.

The royal proclamation that resulted from this conference was published on stelae and disseminated across the nation. The writing on the Rosetta Stone, and occasionally the stone itself, is frequently referred to as the Memphis Decree since the assemblage and coronation took place there. Select portions from the decree are replicated on a stela from Nobaireh, and the decree is recorded on several additional stelae from Elephantine and Tell el Yahudiya.

The monarch was just 13 years old when the decree was issued in 196 BCE; he assumed the throne at a trying time in the Ptolemaic dynasty’s history. After 206 BCE, a short-lived dynasty of “local” rulers was established in Upper Egypt, bringing the reign of Ptolemy IV (221–204 BCE) to an end. Ptolemy V’s suppression of this rebellion’s delta leg and his purported siege of the city of Lycopolis are commemorated in part of the edict that was preserved on the Rosetta Stone.

The Ptolemaic era’s suppression of the revolts has been linked by archaeologists excavating at the Tell Timai site with this period’s indications of unrest and disruption. Although the young king succeeded to the throne upon the death of his father in 204 BCE, he had already assumed the throne as a young child under the watchful guidance of cunning regents who soon set up the assassination of queen Arsinoe III, leaving the young boy without a mother or family regent.

Ptolemy V was crowned by the regents while he was a kid, but his actual coronation wasn’t until he was older and was celebrated by the Memphis Decree on the Rosetta Stone. This latter coronation was postponed for nine years. According to the writing on the Rosetta Stone, the Upper Egyptian rebels persisted after the delta resistance’s defeat until 186 BCE, when royal control over the area was reinstated.

The edict is a complicated document that attests to the negotiation of power between two strong organisations: the royal dynasty of the Ptolemies and the gathered associations of Egyptian priests. According to the wording on the stone, Ptolemy V would restore financial assistance for the temples, raise priestly stipends, lower taxes, grant amnesty to convicts, and encourage well-known animal cults. In exchange, sculptures titled “Ptolemy, defender of Egypt” will be placed in temples all around the country, reinforcing the royal worship.

The king’s birthday, which falls on the thirty-first day of each month, and his accession day, which falls on the seventeenth day, are both festivals that must be observed by the priests. As a result, the king’s power is consistently upheld and the Egyptian religious establishment receives substantial advantages. The Memphis Decree on the Rosetta Stone must be read in the context of similar imperial declarations that are documented on other stelae and are sometimes referred to as the Ptolemaic sacerdotal decrees.

The Mendes stela from 264/3 BCE in the reign of Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the Alexandrian decree from 243 BCE and the Canopus decree from 238 BCE in the reign of Ptolemy III Euergetes, the Raphia decree from 217 BCE in the reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator, the Memphis decree of the Rosetta Stone from 196 BCE, the first and second Philae decrees from 186-185. Archaeological investigations continue to turn up additional components of these stelae, including a fresh example of the Alexandrian decree from el Khazindariya, unearthed in 1999–2000 and pieces of the Canopus decree from Tell Basta discovered in 2004.

4) Writing Material in Ancient Egypt

-Stone: The earliest Egyptian inscription discovered on a stone since predynastic times.

-Papyrus: Papyrus is made up of thick leaves that are connected vertically to papyrus stems, and it has been extensively written on in black and red ink with plumes.

-Ostraka, literally “potteries or stones,” are either smooth limestone cracks that are taken from damaged or building sites. There is a message from the fan holder “Khai” at the top of the work “Neb Nefer” written on a shard of white limestone, demonstrating that its use was not restricted to members of the lowest class. It has been heavily emphasised in demotic literature while being diminished in hieratic discourses. Or obtain the fragments of shattered pottery known as ostraka, which were once used to compose messages before transferring them to papyrus. Most criticisms were made about Ostraka, which was seen as the most restricting option for those unable to afford papyrus.

-Wood: Although it was rarely utilised because it did not preserve writing well, it was occasionally discovered to have heretical text patterns.

-Porcelain, stone, and walls.

5) Famine Stela: Pharaonic diary

A lack of the Nile flood caused a seven-year famine during the reign of King Djoser, King of Upper and Lower Egypt: Neterkhet and founder of the Third Dynasty in the Old Kingdom, which left Egypt in a terrible situation. The king was baffled as there weren’t enough grains, seeds were drying up, people were robbing one another, and temples and shrines were closing. The king asked Imhotep, his architect and prime minister, to search the ancient holy books for a remedy to put an end to the suffering of his people. By the king’s directive, Imhotep travelled to a temple in the historic settlement of Ain Shams (Old Heliopolis), where he learned that the answer was in the city of Yebu (Aswan or Elephantine), the Nile’s source.

The designer of the Djoser pyramid at Saqqara, Imhotep, journeyed to Yebu and went to the Temple of Khnum, where he observed the granite, precious stones, minerals, and construction stones. It was thought that Khnum, the fertility deity, made man out of clay. Imhotep sent king Djoser a travel update during his official visit to Yebu. Khnum appeared to the king in a dream the day after he met with Imhetop, offering to put an end to the famine and let the Nile flow once more in exchange for Djoser restoring the temple of Khnum. As a result, Djoser carried out Khnum’s instructions and gave the Khnum temple a portion of the area’s revenue from Elephantine. The famine and people’s suffering ended shortly after that.

Near 250 BC, under the reign of Ptolemy V, the hunger tale was inscribed on a granite stone on Sehel Island in Aswan. The Stela, which is 2.5 metres high and 3 metres wide, has 42 columns of right-to-left-read hieroglyphic writing. When the Ptolemies inscribed the narrative on the Stela, it already had a horizontal fracture. Drawings of King Djoser’s presents to the three Elephantine gods (Khnum, Anuket, and Satis), who were revered in Aswan during the Old Kingdom, could be found above the inscriptions.

According to his papers kept in the Brooklyn Museum Archives, American Egyptologist Charles Edwin Wilbour found the stone in 1889. Wilbour attempted to interpret the writing on the Stela, but he was only able to decipher the year the narrative was inscribed on the stone. It took 62 years to finish the task after Heinrich Brugsch, a German Egyptologist, read the engravings for the first time in 1891. Four other Egyptologists had to translate and edit the manuscripts. Later, Miriam Lichtheim released the entire translation in a book titled “Ancient Egyptian Literature: A Book of Readings.”

6) Ancient Egyptian Literature

Inscriptions on tombs, stele, obelisks, and temples; myths, stories, and legends; religious writings; philosophical works; wisdom literature; autobiographies; biographies; histories; poetry; hymns; personal essays; letters; and court records are just a few examples of the diverse narrative and poetic forms found in ancient Egyptian literature. Although many of these genres are not often thought of as “literature,” Egyptian studies classify them as such since so many of them, particularly those from the Middle Kingdom (2040–1782 BCE), have such high literary value.

The earliest examples of Egyptian writing are found in offering lists and autobiographies from the Early Dynastic Period (c. 6000–c. 3150 BCE). The offering list and autobiography were carved on a person’s tomb together to inform the living of the gifts and amounts that the deceased was expected to bring to their grave regularly. Regular gifts at cemeteries were significant because it was believed that the dead continued to exist after the failure of their bodies; they needed to eat and drink even after losing their bodily form.

During the time of the Old Kingdom, the Offering List gave rise to the Prayer for Offerings, a standard literary work that would eventually replace it, and the memoirs gave rise to the Pyramid Texts, which were descriptions of a king’s reign and his victorious voyage to the afterlife (c. 2613-c.2181 BCE). These writings were created using a writing system called hieroglyphics, often known as “holy carvings,” which combines ideograms, phonograms, and logograms to express words and sounds (symbols which represent meaning or sense). Due to the laborious nature of hieroglyphic writing, a speedier and more user-friendly script known as hieratic (also known as “holy writings”) developed alongside it.

Although less formal and exact than hieroglyphic, hieratic was built on the same concepts. The arrangement of the characters was carefully considered when writing the hieroglyphic script, which was intended to rapidly and readily transmit information. Demotic script (also known as “common writing”) took the place of hieratic around 700 BCE, and it was used until the emergence of Christianity in Egypt and the adoption of Coptic script in the fourth century CE.

The majority of Egyptian literature was written in hieroglyphics or hieratic script, which was used to write on papyrus scrolls and pottery pots as well as structures including tombs, obelisks, steles, and temples. Although hieratic scripts—and subsequently demotic and Coptic—became the standard writing system of the learned and literate, hieroglyphics continued to be used for monumental constructions throughout Egypt’s history until it was abandoned during the early Christian era.

Although many different types of writing fall under the umbrella of “Egyptian Literature,” for this essay the focus will primarily be on traditional literary works like stories, legends, myths, and personal essays. Other types of writing will be mentioned when they are of particular note. A single article will not be able to adequately describe the vast array of literary works produced by the Egyptian civilization since Egyptian history spans millennia and covers volumes of books.

7) Karnak Temple

Over 2,000 years of continuous usage and expansion characterise the Temple of Amun, one of Egypt’s holiest places. At the end of the New Kingdom, when control of the nation was split between their rule in Thebes in Upper Egypt and that of the pharaoh in the city of Per-Ramesses in Lower Egypt, the priests of Amun who oversaw the administration of the temple became more wealthy and powerful to the point where they were able to seize control of the government of Thebes.

It is believed that the main cause of the collapse of the New Kingdom and the start of the Third Intermediate Period was the development of the priests’ influence and the resultant weakness of the pharaoh’s position (1069 – 525 BCE). Both the Persian invasion in 525 BCE and the Assyrian invasion in 666 BCE caused damage to the temple complex, yet both invasions saw renovations and repairs.

Egypt had been incorporated into the Roman Empire by the fourth century CE, and Christianity was being hailed as the only genuine religion. In 336 CE, the Temple of Amun was abandoned after the emperor Constantius II (r. 337–361 CE) ordered the closure of all pagan temples. The structure was used by Coptic Christians for church services, as shown by the Christian artwork and inscriptions on the walls, but after that, the location was abandoned.

It was unearthed during the Arab invasion of Egypt in the seventh century CE, and at that time it was known as “Ka-ranak,” which means “walled town,” due to the vast quantity of building gathered in a single location. The term “Karnak” has been used for the place ever since the majestic remains at Thebes were identified as such when European explorers first arrived in Egypt in the 17th century CE.

The Early Temple and Amun: After Mentuhotep II united Egypt in around 2040 BCE, Amun (also known as Amun-Ra), a minor Theban divinity, gained popularity. Amun, the greatest ruler of the gods and both creator and preserver of life, was created when the energies of two ancient gods, Atum and Ra (the sun god and creation god, respectively), were merged. Before any buildings were erected, the site of Karnak may have been devoted to Amun. It may also have been sacred to Atum or Osiris, who were both worshipped in Thebes.

The location was previously designated as sacred land since there is no evidence of private dwellings or marketplaces there; instead, only buildings with religious themes or royal apartments were built long after the initial temple was discovered. One may assume that it would be difficult to distinguish between a fully secular edifice and a sacred place in ancient Egypt because there was no distinction between one’s religious beliefs and one’s everyday life. However, this is not always the case. At Karnak, the artwork and inscriptions on the columns and walls make it evident that the location has always been a place of worship.

Wahankh Intef II (c. 2112–2063) is credited with erecting the first monument at the location, a column in Amun’s honour. Ra’s theory that the location was initially established for religious reasons in the Old Kingdom has been refuted by researchers who cite the king’s list of Thutmose III in his Festival Hall. They occasionally draw attention to aspects of the ruins’ architecture that are influenced by the Old Kingdom.

However, as the Old Kingdom (the era of the great pyramid builders) style was frequently imitated by succeeding centuries to evoke the majesty of the past, the architectural connection does not influence the claim. Some academics contend that Thutmose III’s list of kings indicates that if any Old Kingdom emperors erected there, their monuments were destroyed by succeeding monarchs.

Wahankh Intef II was one of the Theban kings who battled the weak central authority at Herakleopolis. He enabled Mentuhotep II (c. 2061–2010 BCE), who eventually overthrew the rulers of the north and united Egypt under Theban rule. Given that Mentuhotep II constructed his burial complex at Deir el-Bahri just across the river from Karnak, some specialists speculate that there was already a sizable Amun temple there at this time in addition to Wahankh Intef II’s tomb.

Mentuhotep II could have constructed a temple there to thank Amun for aiding him in victory before constructing his complex across from it, although this assertion is speculative and there is no proof to support it. There wouldn’t have needed to be a temple there at the time for him to be motivated; he most likely picked the location of his funerary complex because of its closeness to the sacred place across the river.

The Middle Kingdom’s Senusret I (r. c. 1971–1926 BCE) erected a temple to Amun with a courtyard that may have been meant to commemorate and emulate Mentuhotep II’s funeral complex across the river. Senusret I is the first known builder at Karnak. Therefore, Senusret I would have designed Karnak in reaction to the tomb of the great hero Mentuhotep II. All that is undeniably known, however, is that the place was revered before any temple was built there, thus any assertions along these lines remain hypothetical.

The Middle Kingdom kings who succeeded Senusret I each made additions to the temple and extended the area, but it was the kings of the New Kingdom who turned the modest temple grounds and structures into a massive complex with incredible scale and attention to detail. Since the 4th Dynasty ruler Khufu (r. 2589–2566 BCE) constructed his Great Pyramid at Giza, nothing comparable to Karnak has been attempted.

The Design & Function of the Website: Karnak is made up of several pylons, which are colossal entrances that taper to cornices at their tops and lead into courtyards, halls, and temples. The first pylon leads to a large court that beckons the visitor to continue. The Hypostyle Court, which spans 337 feet (103 metres) by 170 feet, is accessible from the second pylon (52 m). 134 columns, each 72 feet (22 metres) tall and 11 feet (3.5 metres) in diameter, support the hall.

Long after Amun’s worship acquired prominence, there was still a precinct dedicated to Montu, a Theban combat god who may have been the original deity to whom the place was first dedicated. To honour Amun, his wife Mut, a goddess of the sun’s life-giving rays, and their son Khonsu, a goddess of the moon, the temple was divided into the three sections Bunson describes above as it grew. They were known as the Theban Triad and were the most respected gods until the cult of Osiris and its triad of Osiris, Isis, and Horus overtook them.

The Middle Kingdom’s initial temple to Amun was replaced with a complex of temples to several gods, including Osiris, Ptah, Horus, Hathor, Isis, and any other notable deity to whom the New Kingdom pharaohs thought they owed a duty of gratitude. The gods’ priests oversaw the temple, gathered tithes and donations, gave out food and advice, and translated the gods’ intentions for the populace. By the end of the New Kingdom, over 80,000 priests were working in Karnak, and the high priests there were wealthier than the pharaoh.

Beginning with the reign of Amenhotep III, and possibly earlier, the religion of Amun presented challenges for the New Kingdom kings. No monarch ever attempted to considerably reduce the authority of the priests, except Amenhotep III’s half-hearted attempts and Akhenaten’s spectacular reformation, and as was already said, every king continuously donated to Amun’s temple and the riches of the Theban priests.

Karnak continued to command respect even during the Third Intermediate Period’s discord (roughly 1069 – 525 BCE), and the Egyptian pharaohs continued to add to it as much as they could. Egypt was conquered by the Assyrians under Esarhaddon in 671 BCE, and subsequently by Ashurbanipal in 666 BCE. Thebes was destroyed during both invasions, but the Temple of Amun at Karnak was left standing. When the Persians conquered the nation in 525 BCE, the same pattern occurred once again. In fact, after destroying Thebes and its magnificent temple, the Assyrians gave the Egyptians the command to reconstruct it because they were so pleased.

Egyptian authority and work at Karnak resumed when the pharaoh Amyrtaeus (r. 404–398 BCE) drove the Persians out of Egypt. Nectanebo I (r. 380–362 BCE) erected an obelisk and an incomplete pylon to the temple and constructed a wall around the area, possibly to fortify it against any more invasions. The Temple of Isis at Philae was constructed by Nectanebo I, one of the great monument builders of ancient Egypt. He was one of the country’s last native Egyptian monarchs. Egypt lost its independence in 343 BCE when the Persians came home.