Herod the Great: Judea’s Builder King and Ruthless Tyrant

Updated On: November 20, 2023 by Maha Yassin

Beneath the shadow of the ancient Western Wall in Jerusalem lies the echo of a legacy that has endured millennia, woven by a king whose reign was as grandiose as it was ruthless. Herod the Great, a name that evokes the image of splendid temples and formidable fortresses against the landscape of Judean deserts, was not merely a builder of cities but a shaper of history.

From 37 to 4 BCE, his rule was marked by an unparalleled architectural revolution in Judea, yet his story is tinged with the darker hues of intrigue and tyranny. In an era where kings were often puppets of empires, Herod stood out—a client of Rome, yet a master of his realm, a Jewish monarch of Arab descent, whose political acumen kept him on a throne that seemed as precarious as the cliffs of Masada.

In this article, we will take a journey through history to learn about the intriguing life of Herod the Great. So, if you’re a history buff or just a curious person like us, this article will blow your mind!

Key Takeaways

- Herod the Great was a Roman Jewish king who ruled over Judea from 37-4 BCE.

- He rose to power under Roman patronage and established himself as a prominent ruler.

- Herod embarked on numerous grand building projects throughout his kingdom, including constructing Jerusalem’s Second Temple and expanding the Western Wall.

- Herod the Great married at least ten women during his life, mostly to secure political alliances through marriage.

Biography and Reign of Herod the Great

Herod the Great, a Roman Jewish king, rose to power in ancient Judea and established himself as a prominent ruler under the reign of the Roman Empire. He embarked on numerous building projects throughout his kingdom, leaving behind a legacy of architectural marvels that continue to be admired today. However, neither rising to power nor maintaining it was easy for Herod. He overcame several obstacles to establish himself as the strong ruler we learn about today.

The Early Life of Herod (Before He Was Great)

Herod the Great was born around 73 BCE into a politically well-connected family of Idumean descent who had converted to Judaism. His father, Antipater, was a high-ranking official who established strong ties with Rome, and his mother, Cyprus, was an aristocrat.

Raised in a milieu of power and privilege, Herod received a Roman education, which ingrained in him both the cultural sophistication and political acumen of the time. His youth was marked by the influential relationships he formed with the Roman elite, including friendships with those in the line of succession in Rome, which would later prove invaluable.

The Rise to Power (Becoming Great)

Herod’s pathway to power began in earnest when his father, Antipater, was appointed procurator of Judea by Julius Caesar. Following his father’s assassination, Herod demonstrated his own political shrewdness. He started his ascent as the governor of Galilee, a position he utilized to establish his reputation for decisive action against banditry and insurrection, gaining the favour of Rome. His loyalty to Rome was further cemented when he supported the Roman general Mark Antony during the Roman civil war.

After the defeat of Antony and Cleopatra, Herod managed to secure his position by swiftly shifting his allegiance to Octavian, who would become Emperor Augustus. Impressed by Herod’s political agility and usefulness as an ally, Augustus bestowed upon him the kingship of Judea in 37 BCE. Herod’s rise to power was also facilitated by his strategic marriage to Mariamne, a princess from the Hasmonean dynasty, which helped to legitimize his rule among the Jewish populace.

Herod always knew how to play the game of politics, and being born and raised in the Roman Empire helped educate him even further. Loyalty was not a priority for him as long as he kept his power and influence.

The Ruler of Judea (Finally Great!)

Once king, Herod embarked on an ambitious economic and cultural development program, transforming Judea into a major centre of commerce and Hellenistic culture. He was a prolific builder; his projects included the magnificent expansion of the Second Temple in Jerusalem, the construction of the fortress-palace of Masada, and the development of the port city of Caesarea Maritima. These endeavours not only bolstered the economy but also left a permanent mark on the architectural landscape of the region.

However, Herod’s reign was not without controversy. His heavy taxation to fund his building projects, his embrace of Hellenistic culture, and his ruthless suppression of dissent made him unpopular among certain factions of his subjects. The New Testament paints Herod as a tyrant, highlighting the infamous massacre of the innocents, although historical evidence for this event is debated among scholars.

The Architectural Grandeur of Herod The Great

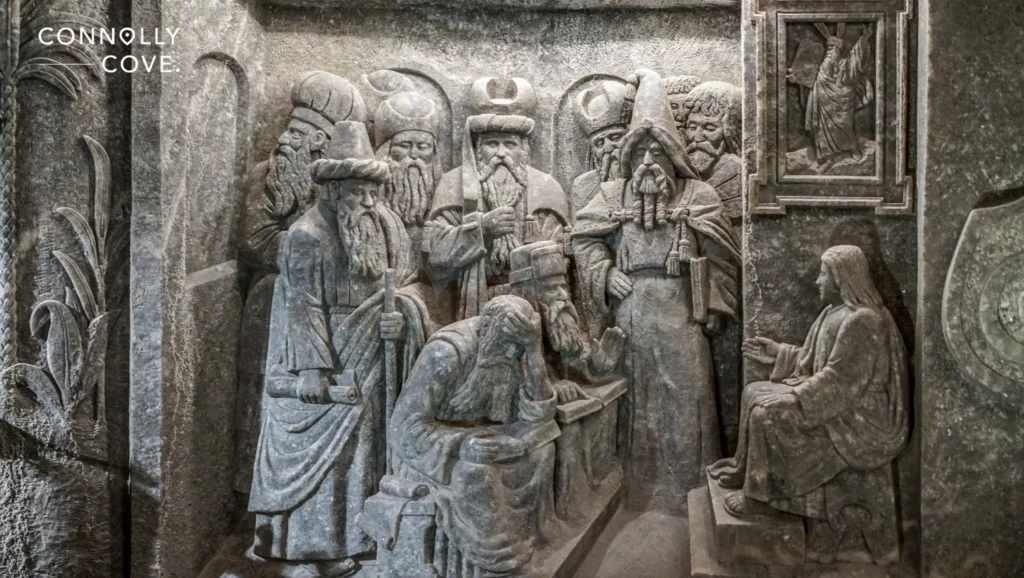

The most significant building attributed to Herod the Great is undoubtedly the Second Temple in Jerusalem, particularly its expansion and renovation, which is often referred to as Herod’s Temple. Herod undertook this colossal project around 20 BCE, aiming to transform the existing modest structure into a magnificent temple complex rivalling the Roman world’s grandest edifices.

The Second Temple

Herod’s Temple was an architectural marvel of its time, reflecting Herod’s desire to impress his subjects and Roman allies. The Temple itself was enlarged and overlaid with white marble and gold, creating an imposing and splendid sight. The surrounding complex was expanded to include spacious courts, grand colonnades, and a massive new altar. The Royal Stoa, a basilica at the southern end of the Temple Mount, was one of the most impressive parts of the expansion, serving as a major public space and a commercial centre.

The Western Wall

A significant and lasting feature of Herod’s construction was the expansion of the Temple Mount platform, which involved the creation of an immense retaining wall. This wall is famed for the Western Wall, also known as the Wailing Wall, which is a segment of the ancient wall that once surrounded the Temple Mount’s courtyard and is considered the most sacred site recognized by Judaism today.

Herod’s Temple stood as a testament to his ambition and served as a central place of worship for the Jewish people until its destruction by the Romans in 70 CE during the First Jewish-Roman War. While the Temple itself no longer stands, the remnants of Herod’s construction, particularly the Western Wall, continue to bear witness to the grandeur of his vision.

The Temple’s significance transcends its physical presence; it has become a symbol of ancient Jewish heritage and remains a focal point for Jewish prayer and yearning. Herod’s Temple, thus, stands out as the most significant and enduring of his many building projects, encapsulating his legacy as a master builder with a complicated history.

The Many Wives and Children of Herod the Great

Herod the Great’s personal life was as tumultuous and complex as his political reign. His family relationships were characterized by both deep affection and profound tragedy, influenced by the political machinations of the time.

Wives and Marriages

Herod was married at least ten times, in part because marriage was a tool for political alliances and other times to satisfy his personal pleasure. Each of his wives played a role in his ascension to power or his retaining of it. Here are some of his most famous wives:

- Doris: Herod’s first wife, whom he married before he became king. Together they had a son, Antipater. He later divorced Doris to marry Mariamne I.

- Mariamne I: A member of the Hasmonean dynasty, her marriage to Herod was meant to solidify his position with the Jewish populace. They had two sons, Alexander and Aristobulus IV. Accusations of infidelity and conspiracy led to her execution, an event that reportedly caused Herod great anguish.

- Malthace: A Samaritan woman and mother to Archelaus and Antipas, two sons who played significant roles in the succession after Herod’s death.

- Cleopatra of Jerusalem: She was the mother of Herod Philip II.

The political nature of Herod’s marriages often led to familial strife, as the intermingling of different factions within his household created a hotbed for intrigue and suspicion.

Children and Succession

Herod fathered numerous children. His sons were often educated in Rome, a gesture both of favour with the Roman elite and a means to secure their future positions. However, Herod’s later life was marked by familial betrayal and tragedy:

- Antipater, his firstborn son with Doris, was executed in 4 BCE after being found guilty of plotting to murder Herod.

- Alexander and Aristobulus IV, his sons with Mariamne I, were also executed on charges of treason, reflecting the paranoia that gripped Herod in his later years.

- Archelaus inherited Judea but was deposed by the Romans in 6 CE due to his unpopularity.

- Antipas, known as Herod Antipas, became the tetrarch of Galilee and Perea and is the Herod mentioned in the New Testament during the ministry of Jesus.

- Philip was a tetrarch of the regions northeast of the Jordan River.

These events are indicative of the brutal measures Herod took to protect his throne, which included the murder of several family members whom he suspected of usurping his power.

Legacy

Herod’s personal life was marked by suspicion and the grim irony that his lineage, meant to secure his dynasty, instead became a source of its near ruin. The dynastic struggles, accusations, trials, and executions of his own family members all paint a picture of a ruler who was as deeply feared by his own kin as he was by his subjects.

His marriages and progeny, intertwined with his political manoeuvres, left a legacy of a ruler who, even in his quest for family and succession, could not escape the shadows of distrust and despotism that ultimately coloured his rule.

The Death of Herod the Great

Herod the Great’s death is a subject of historical interest due to the dramatic nature of his final days and the significant impact his passing had on the geopolitics of the region.

His Final Illness

Herod’s health began to deteriorate significantly in the final years of his life, marked by chronic pain, complications from various diseases, and severe depression, likely exacerbated by the family turmoil and the executions of several of his sons. Historical accounts, particularly by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, suggest that Herod suffered from an excruciating and debilitating illness, which some modern physicians have retrospectively diagnosed as chronic kidney disease complicated by gangrene.

His Last Acts

As Herod’s condition worsened, his mental state became increasingly unstable and his behaviour more erratic. He was consumed by paranoia and fear of being overthrown, which led to the aforementioned execution of his own family members, including his favoured wife Mariamne and their sons Alexander and Aristobulus IV, as well as his eldest son Antipater.

In his final act of cruelty, aware that his death would be met with rejoicing rather than mourning by the Jewish populace, he reportedly ordered the arrest of numerous distinguished men from across Judea with instructions that they be killed upon his death to ensure that there would be mourning in Judea. However, this order was not carried out after his death.

Death and Burial

Herod died in 4 BCE after a reign of 33 years. His death was reportedly agonizing, and Josephus provides a vivid description of his symptoms, which have led to much speculation about the exact nature of his illness. Herod’s body was transported to his fortress palace of Herodium for burial, as per his wishes. Herod had constructed an elaborate mausoleum for himself, which archaeologists believe they have discovered at the site of Herodium.

Aftermath and Succession

Herod’s death triggered a succession crisis. Although he had altered his will multiple times, the final version divided his kingdom among his surviving sons. Archelaus was appointed ethnarch over Judea, Samaria, and Idumea; Antipas became tetrarch of Galilee and Perea; and Philip was made tetrarch of the regions to the northeast. These appointments, ratified by Augustus, would shape the region’s political landscape for the following decades.

Herod’s death marked the end of an era in Judean history—a period characterized by great architectural achievements and profound political change but also by tyrannical rule and brutal family strife. Herod’s legacy, both physical in the structures he built and historical in the narratives passed down through generations, continues to influence the perception of this complex and enigmatic figure.

Herod, the Great’s legacy, is a study in contrasts: a master builder whose magnificent works like the Second Temple still evoke awe and a ruler whose reign was marred by tyranny and familial tragedy. He was a man of vision who shaped Judea indelibly, yet he also personified the dark side of absolute power. In the annals of history, Herod remains a complex figure, emblematic of the eternal human struggle between greatness and hubris, leaving a legacy that continues to be both celebrated and debated.

What did Herod the Great do to Jesus?

When Herod Antipas (Herod the Great’s son) learned of the birth of the Jewish Messiah, he ordered the murder of all children aged two and under in Bethlehem to be killed. He was afraid Jesus would challenge his rule over Judea.

What was Herod the Great known for?

He was known as the ruler of Judea, assigned by the Roman Empire. He is also known for his grand architectural projects in Judea.

Was King Herod from Egypt?

King Herod was born around 72 BCE in Idumea, south of Judea. In modern times, this land is called Palestine.