Victorian Belfast: An Architectural Guide

Updated On: November 07, 2023 by Ciaran Connolly

The Victorian Era, 1837 – 1901, was the period of Queen Victoria’s reign. It was an era of great development and dramatic change, transforming England from a traditionally agricultural and rural country to one of advanced industrialisation and urban sensibility. This same transformation held true for Victorian Belfast. Advances in medicine, technological and scientific knowledge were made, including the ability to mass-produce, steam engines and railways, and gas and electric light. It also saw advances in and emphasis on leisure activities (notably for the middle and upper classes, less so for those worse off) such as seaside ventures, and the building of libraries, theatres, and music halls.

The mood of the kingdom can be characterised by a Protestant work ethic, with importance placed upon the family unit and its values, as well as religious observation and institutional faith. It was also a period of dehumanisation of the lower classes, with the country’s poorest suffering from dangerous overwork, child labour, and intense pollution.

The kingdom was shaken by the publication of On the Origin of Species (or, more completely, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life) by English naturalist, geologist and biologist Charles Darwin in 1859. The revival of the Gothic and Romantic tradition followed as resistance to the rationalism that dominated the Georgian period before Victoria’s reign. Interest in science and evolution often went hand in hand with the occult and mysticism.

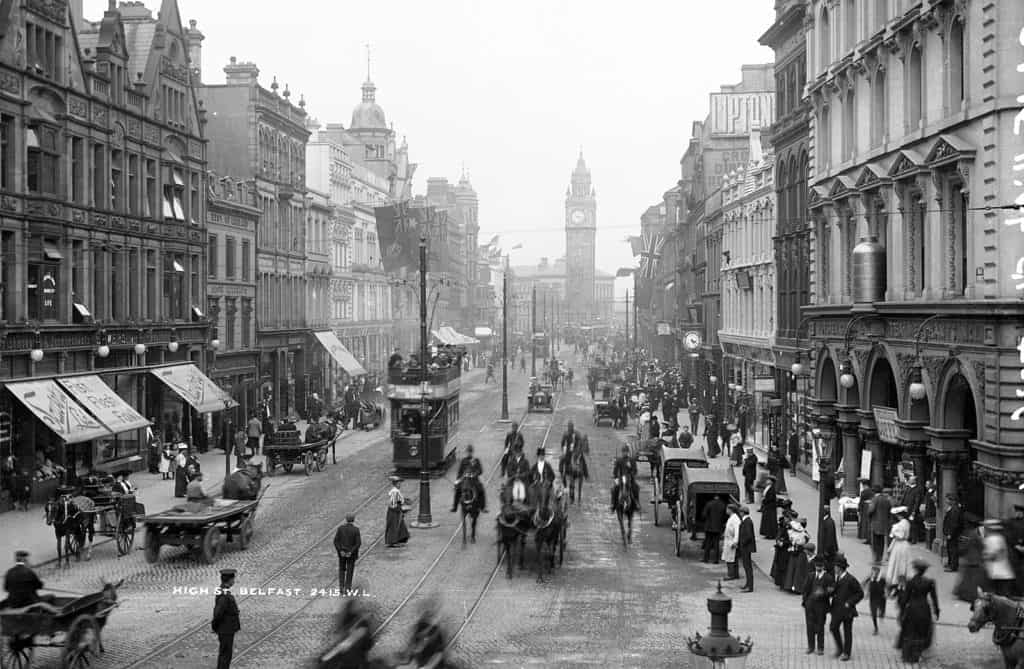

What was Victorian Belfast like?

Belfast, author Paul Larmour explains, is a “comparatively young city” with “no ancient castle or cathedral at its heart”. Wishing to advance beyond its status as a relatively unremarkable town, from the 1780s to the 1820s Belfast improved its harbour, established iron founding and shipbuilding (for which it was to be known for forever), and founded banks, educational institutions, and societies of an intellectual nature. This public spirit by the people of Belfast earned it the name of ‘Athens of the North’. It was granted city status by Royal charter in 1888.

The buildings in early Victorian Belfast were largely affected by what was going on in the city at the time: epidemics. The city was struck by adverse effects of the Great Famine, cholera, and typhus. In fact, Queen Victoria’s marriage was not celebrated with the planned fireworks and illuminations as the city collectively decided to put the money to better use: the £178 (roughly £40,000 in today’s economy) built a Fever Hospital, a Workhouse and the Union Hospital (now City Hospital).

What is Victorian Belfast Architecture?

At its most basic, architectural style is characterised by features that make a building or structure historically identifiable or notable. The name Victorian Architecture derives from the British and French tradition of naming a style of architecture after the reigning monarch of the time.

Victorian Architecture, particularly in Belfast, is unique in that it doesn’t conform to one specific style; rather, it encompasses a wide variety of different styles that reflect the ideologies, culture, and beliefs of both the individual architects and wider society. Particularly popular during the Victorian era were Medievalesque, Neoclassic styles like the ancient Greeks and Romans, symmetrical Palladianism, and Gothic and Romantic styles that stood in opposition to the previously mentioned styles. It was an era of mix-matched conformity and resistance, making it especially interesting from an architectural standpoint.

The key styles were as follows:

- Gothic Revival/Neo-Gothic (early 19th century): in contrast to the rising Neo-classical sensibilities permeating British culture at the time, this style emphasised creativity and the sublime human spirit, inspired by the architecture of the Romantic Medieval era. It is characterised by decorative patterns, finals (elemental marking the top of an object to emphasis the apex of a dome, spire or tower). It often incorporated cast-iron, which has an ideological value in that it represents human strength, fortitude, honour and courage

- Jacobean (1830 – 1870): this style reflected a Renaissance revival, harking back to the styles popularised during Elizabeth I and James I’s rule. They’re Shakespearean, what you could call a Neo-Renaissance style. It was influenced by Italian Mannerism, which sought to represent ideal beauty in contrast to natural beauty, utilising distortion and exaggeration, and Baroque architecture, a more theatrical Renaissance style popular in 16th century Italy

- Neo-Grec (1845 – 1865): a Neo-classical revival inspired by the thoroughness and consistency of ancient Roman and Greek temples

- Romanesque Revival (mid-19th century): Also known as Norman architecture, this style was inspired by the massive structures popular in the 11th and 12th centuries. It combined Roman and Byzantine qualities, resulting in buildings with thick walls, round arches, sturdy pillars, and decorative arcading (succession of contiguous arches)

- Second Empire/Napoleon Style (1852 – 1871): this was a highly eclectic style that originated in France. It is characterised by a single structure that incorporates a mixture of different historical styles to create something unique and new

- Queen Anne Revival (1870 – 1910): a stick-like, linear style that became widely popular in the US during the hedonistic 1920s

Arts & Crafts Movement (1880 – 1920): a precursor to Modernism, this style emphasised human craftsmanship using simple tools. It was a pure and humanistic style that stood as a protest against industrialisation and the dehumanisation of workers

The Best of Victorian Belfast Architecture

Palm House, 1839 – 1840 (College Park Botanic Avenue Belfast County Antrim BT7 1LP)

Botanic Gardens were first established in 1828 by the Belfast Botanic and Horticultural Society and have been enjoyed by the people of Belfast as a public park since 1895. Palm House stands as an important cultural and historical landmark. Designed by Sir Charles Lanyon, it is one of the oldest examples of a curvilinear iron and glass structure anywhere in the world. Its two wings were completed in 1840 and are the earliest known work of renowned ironmaster Richard Turner, who went on to create the Palm House at Kew Gardens and the Winter Gardens in Regent’s Park, London.

(Source: Discover Northern Ireland)

Queen’s University Lanyon Building, 1846 – 1849 (University Rd, Belfast BT7 1NN)

Queen’s University was one of the three Queen’s colleges established in Ireland in 1845 to provide non-denominational higher education (others located in Cork and Galway). The Lanyon Building, named for its chief designed Charles Lanyon, is a red-brick Tutor style building designed for maximum picturesque effect and was modelled after the 15th-century Founders Tower at Magdalen College. It is fairly close in design but it decidedly taller and narrower. Modelling it after the Founders Tower was a way to establish pedigree and authority.

Elmwood Hall, 1852 – 1862

Now one of the city’s most popular events venue, Elmwood Hall was formerly Elmwood Presbyterian Church. It was designed by talented amateur John Corry in a Lombardo-Venetian style. Paul Larmour argues that Elmwood Hall also has John Ruskin influences, evident in such details as the loggia which presents a series of botanical studies.

(Source: waterfront.co.uk)

Ulster Hall, 1859 – 1862

The Ulster Hall was one of the largest music halls in Britain when it first opened. It was designed by William J. Barre of Newry, Co, Down, who won the chance to design it in a competition. It is Italianate in style, with Neo-Classical keystones and Roman Corinthian columns. Although described by some as elephantine, the Ulster Hall is an understated hidden gem.

(Source: qub.ac.uk)

Albert Memorial Clock, 1865 – 1869

Known affectionately by the locals as Belfast’s Leaning Tower of Pisa, the Albert Memorial Clock 141-feet high and was designed by William J. Barre in 1865 after winning a competition to design a memorial to the Prince Consort. It is a High-Victorian version of the Big Ben clock tower at Westminster, with an eclectic mix of Italian and French Gothic with early Renaissance gargoyles and lions at its base.

It was infamous after its completion for being a prostitute meeting point, where visiting sailors could find sexual services. Many years later it was featured in the 1947 film Odd Man Out starring James Mason.

Its current angle is due to it being built upon slob land at the head of an old tidal dock, meaning the river courses around its foundation.

(Source: curiousireland)

Grand Opera House, 1894 – 1895

The Grand Opera House is a Belfast’s most popular theatre, designed by the most prolific theatre architect of the era, Frank Matcham. According to their website, the Grand Opera Houses’ ‘first season included burlesque acts, musical comedies, farces and melodramas. There was also a market for classical opera and drama with regular performances of Shakespeare. The theatre flourished during its early years, offering escapism to the worlds of comedy and drama, including a visit by Gracie Fields in 1933 which was a sold-out success.’

It was designed by Matcham to be deliberately eye-catching, in an early art nouveau wat. Larmour sees it as a ‘bizarre jumble of Renaissance elements with onion-shaped ventilator domes placed on top. The oriental suggestion here is compounded inside where Indian motifs, including elephant heads, are brought into play in a lavish and rather Baroque ensemble’.

(Source: The Stage)

The Crown Bar, 1885 & 1898

The Crown Bar, across the road from Great Victoria Street train station, is a fantastic example of late Victorian architecture. It features a Corinthian styled plastered upper façade. Its exterior is gaudy, and its interior is a mix-match of colourful tiles and stained glass. Its entrance is guarded by classic Gothic lions and griffons, the shields held up by their paws bearing the inscriptions ‘verus amor patriae’ and ‘audaces fortuna juval’.

(Source: The Victorian Web)

Belfast City Hall, 1896 – 1906

Situated on the previous site of White Linen Hall, plans for Belfast City Hall began when Queen Victoria made Belfast a City. It cost £369,000 to build, the funds coming from the profits of the city’s gasworks industry.

It is a key example of the Baroque Revival in Britain. It is characterised by a combination of English 17th and 18th century Classicism, Neo-Palladian symmetrical walls, and a rusticated ground floor. It’s central dome (made with copper, its distinct contemporary green the result of natural corrosion from fresh air) was inspired by St. Paul’s Cathedral and Greenwich Hospital.

Its interior features Italian and Greek marble and Venetian-style windows. It’s Whispering Gallery is what Paul Lamour calls ‘one of the grandest architectural spaces in Ireland’.

(Source: Giorgio Galeott)

Victorian Belfast Architecture: Honourable Mentions

- Belfast Castle, 1868 – 1870 (Antrim Rd, Belfast BT15 5GR): situated in the highly Romantic mountains of Belfast, it is a large mansion in a Scottish baronial style built for the Marquis of Donegal

- Methodist College, 1865 – 1868 (1 Malone Rd, Belfast BT9 6BY): a fine example of Gothic Revivalist style inspired by 14th century English architecture

- Queen’s Arcade, 1880 (4 Queen’s Arcade, Belfast BT1 5FF): the arcade and the building above it was designed by James McKinnon for developer George Fisher

- Belfast Central Library, 1883 – 1888 (Royal Ave, Belfast BT1 1EA): refined and Classical in design, with beautiful French windows and a domed Corinthian columned reference library

- St. George’s Market, 1890 – 1896 (East Bridge St, Belfast BT1 3NQ): a traditional design that adhered to the utilitarian needs of the locals. Cheap and practical, yet charmingly handsome

- Crumlin Road Goal, 1843 – 1845 (53-55 Crumlin Rd, Belfast BT14 6ST): C. E. B. Brett describes the fortress as having a ‘radical layout’, with ‘the sinister manner of Guilo Romano’

- Queen’s Graduate School (formerly Queen’s University Library), 1868 (University Rd, Belfast BT7 1NN): Romantic Gothic with intricate French-detailed windows