From Reeds to Records: The Journey of Ancient Egyptian Papyrus

Updated On: April 23, 2024 by Noha Basiouny

In the arid expanses of ancient Egypt, where the golden sands meet the fertile banks of the Nile, a civilisation emerged that continues to enchant the world with its mysteries, colossal monuments, and profound knowledge. At the heart of this ancient society’s ability to immortalise their existence was the remarkable invention of papyrus.

As a writing material and a symbol of eternal life, papyrus played a pivotal role in the preservation of Egyptian heritage. On its surfaces were recorded the complexities of daily life, the grandeur of royal decrees, and the profundities of religious texts. Beyond its practical uses, the papyrus scroll became a canvas for artistic expression, adorned with intricate hieroglyphics and vibrant illustrations that still captivate scholars and enthusiasts alike.

This article will dive deeper into the rich history of papyrus, from its cultivation in the marshy deltas of the Nile to its role as a vehicle for administration, art, and literature. It will explore the meticulous process of its production, the cultural significance it held in the lives of the Egyptians, and the incredible legacy it has left behind.

So bring in a cup of coffee, and let’s hop into it.

Papyrus

Papyrus is a type of paper-like writing material that was used extensively in ancient Egypt and dates back thousands of years. The word “papyrus” refers both to the writing material itself and to the aquatic plant, cyperus papyrus, from which the writing itself was produced.

Cyperus papyrus is a tall wetland sedge that once grew abundantly along the Nile River in Egypt and in parts of the Mediterranean region. The stalk of the plant consists of a fibrous inner pith that is surrounded by a tougher outer rind.

Ancient Egyptians harvested papyrus primarily for the purpose of making paper as well as other various items, including boats, mats, rope, and sandals—ancient Egyptians were reportedly the first in history to ever make and wear sandals, beautiful, stylish, colourful sandals.

Significance

The stunning invention of papyrus was deeply integrated into the very identity of ancient Egyptian civilisation and was the cornerstone of its culture and administration. It facilitated the structured governance that characterised the pharaonic era and served as the medium upon which the intellectual endeavours of scribes and the sacred words of priests were recorded and preserved.

Here are a few facets of ancient Egyptian society that best analyse the significance of this type of paper.

1. Record-Keeping and Administration

Ancient Egypt was a complex society with a well-developed system of civil administration. The use of papyrus allowed for the creation of a variety of administrative documents, such as tax records, census data, legal documents, and inventories of goods.

This efficient record-keeping was vital to the management of granaries, the organisation of large workforces (like those needed for pyramid construction), and the collection of taxes that sustained the state.

2. Literature and Education

Papyrus was the medium for scribes and scholars. Works of literature, such as “The Tale of Sinuhe ” and “The Book of the Dead,” were transcribed on papyrus, allowing them to be passed down through generations.

Education relied on this writing material as well; students practised writing hieroglyphics and hieratic script on papyrus sheets. It was in the “House of Life,” a kind of library/archive attached to temples, where many manuscripts containing religious, medical, and scientific texts were kept.

3. Communication

In a time long before electronic communication, papyrus allowed for messages to be sent across distances. Diplomatic correspondence between Egypt and its neighbours was conducted through letters written on papyrus, facilitating the exchange of ideas and the negotiation of treaties.

Contracts, wills, and legal disputes were also documented on papyrus, giving a formal and durable form to agreements and legal proceedings. This practise laid early foundations for the rule of law and the documentation of individual rights and property.

4. Religion and Ritual

Religious texts were primarily written on papyrus. The famous “Book of the Dead,” a collection of spells which was believed to protect and aid the deceased in the afterlife, was typically inscribed on a papyrus scroll placed in the tomb of the departed.

Rituals often involved reading from sacred texts, and this precious invention enabled these texts to be portable and accessible.

5. Art and Decoration

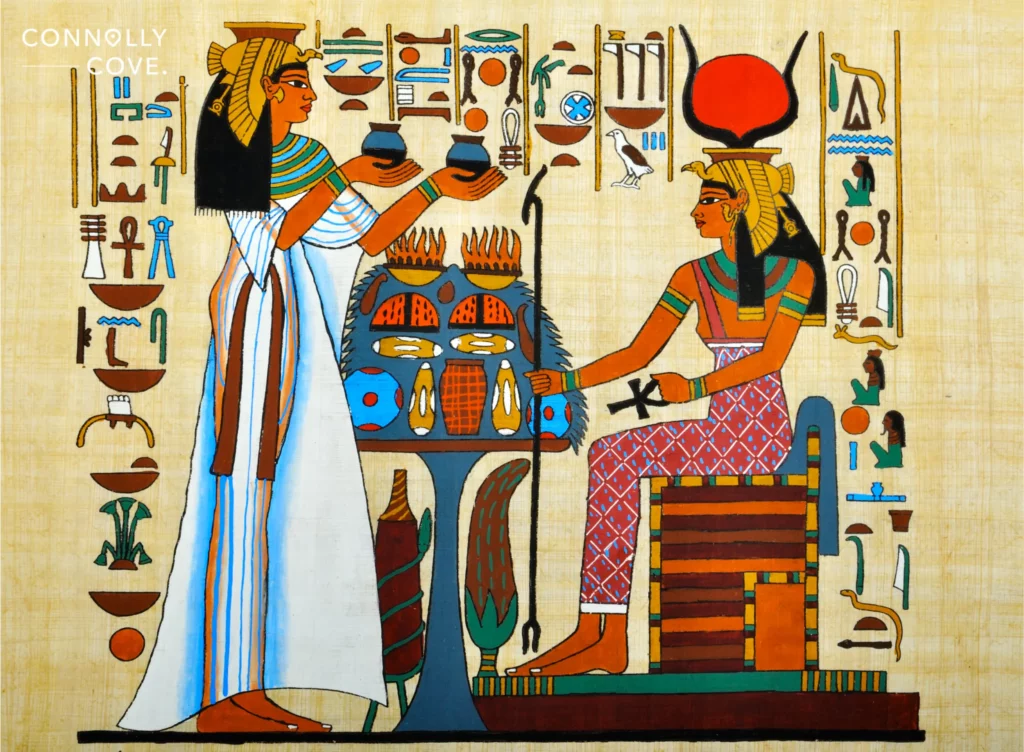

Beyond its practical use as a writing material, papyrus was also a canvas for art and decoration in ancient Egypt. Its use as a medium for artistic expression was a natural extension of its role in Egyptian culture and showcased the versatility of this material.

For instance, illustrated manuscripts often contained elaborate drawings and paintings that accompanied the text, including depictions of gods and goddesses, scenes from the afterlife, and narratives of mythological events. These artistic works not only displayed the skill of Egyptian artists but also served religious and didactic purposes.

In addition, the aforementioned “Book of the Dead” was not just a collection of spells but also a richly decorated scroll that often contained vivid illustrations of the deceased’s journey through the afterlife.

Illustrations were common in literary works as well. Poems and stories might be accompanied by relevant imagery, which not only served to embellish the text but also to provide a visual narrative that complemented the written word.

History

The exact origin of the use of papyrus as a writing material in Egypt is shrouded in the mists of prehistory. However, it is widely believed that its use began sometime during the fourth millennium BC. This was the Predynastic period, before the Kingdoms of Lower and Upper Egypt were unified around 3100 BC by the first Pharaoh, Narmer.

During the Early Dynastic Period (3100 – 2686 BC), with the founding of the First Dynasty and the establishment of a centralised state, the use of papyrus likely became more widespread. The need for record-keeping and administration in a growing and complex society necessitated the development of convenient and efficient writing material.

Papyrus use reached its height during the Old Kingdom (2686 – 2181 BC), a time known for the building of the Great Pyramids of Giza, when the state administration became highly developed. This era required meticulous records concerning labour, resources, and goods distribution, which were often documented on this paper.

By the time of the Middle Kingdom (2055 – 1650 BCE), the second of three golden ages in ancient Egypt, papyrus was firmly entrenched as an integral part of Egyptian culture.

This period, known for its literature, saw many classic works of Egyptian writing that were likely composed on papyrus. It is also from this period onward that larger numbers of documents have survived, many detailing legal matters and government records.

The New Kingdom (1570 – 1069 BC) was the most prosperous period of the entire Egyptian civilisation, where the Egyptian empire witnessed an explosion of the arts and literature. Papyrus was used extensively to record the exploits of pharaohs, the construction of temples, and the wealth of religious texts.

As Egypt’s influence grew, so did the export of its distinct paper, which became highly sought after for writing materials throughout the Mediterranean. By the Late Period (664 – 332 BC), the Greek and Roman cultures were also using papyrus, importing it from Egypt, which held a monopoly on its manufacture.

With the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great and the subsequent Ptolemaic Dynasty (332 – 30 BC), papyrus continued to be a significant export. It was also during this period that the famous Library of Alexandria was established, where countless scrolls filled its shelves before the library’s tragic demise.

The Roman Period (30 BC – 395 AD) witnessed the continued use of papyrus in Egypt even as the material began to face competition from parchment, which popped up out of nowhere like ChatGPT, and started, slowly but steadily, taking the lead. It was not long until parchment almost completely superseded papyrus due to its greater durability and ease of production in other climates.

Papyrus production and use gradually declined in late antiquity, particularly after the Muslim conquest of Egypt in the seventh century AD. The introduction of paper-making techniques from the East began to replace papyrus, which, by this point, was used more for ceremonial and artistic purposes rather than for everyday writing.

Production

The production of papyrus was a skilled and labour-intensive process that capitalised on the abundant plant that thrived in the marshy areas of the Nile Delta. The entire procedure reflected the ingenuity of ancient Egyptians and their ability to harness natural resources.

That said, papyrus production was not just a craft but an essential industry in ancient Egypt. The skill of the papermakers determined the quality and usability of the finished product, which had a significant impact on the daily life, culture, and economy of the civilisation, as we discussed earlier. Given that countless documents and scrolls have survived to date, we can pretty much work out how skilful those papermakers were.

So here is a glimpse of the ancient Egyptian papyrus-making process.

1. Harvesting and Preparing

The first step was to gather the tall papyrus stalks, which were abundant along the banks of the Nile River. Harvesters would select mature stems, which could reach up to 4.5 metres in height, and cut them near the base.

Once harvested, the outer rind of the stalk was peeled away to reveal the soft and pithy interior. This pith was then sliced lengthwise into thin, even strips. The quality of the paper depended greatly on the precision of these strips; the best paper was made from the innermost pith.

2. Soaking and Laying

The strips were soaked in water for a period of time, which varied according to the desired quality of the finished product. Soaking allowed the strips to become pliable and also removed some of the sugars and sap, for these could cause the papyrus to turn yellow and become brittle over time.

After soaking, the strips were laid out on a flat surface. They were placed side by side in a horizontal layer and then covered with a second layer of strips laid vertically. This cross-layering technique created a sturdy and durable sheet. It is worth noting that the best sheets had the fibres running parallel to the longest side of the sheet, as this would be the direction of writing.

3. Pressing, Drying and Polishing

Once the layers were arranged, the sheet was pressed, either by hand or using a press. The natural sap within the papyrus acted as an adhesive, bonding the layers together as they dried. The pressing had to be firm enough to create a solid sheet but still gentle enough not to crush the fibres.

The freshly pressed sheets were then left to dry, often under the Sun. This step requires careful monitoring, as the environment needed to be neither too damp (which could prevent proper drying) nor too dry (which could make the sheets brittle).

Once the sheets were dry, they were polished to create a smooth surface that was conducive to writing. A stone or shell was used to rub the surface to smooth out any irregularities and provide a more uniform texture for scribes to work on.

4. Joining and Cutting

For documents that required more length than a single sheet, multiple papyrus sheets were glued together at the edges to form a scroll. These scrolls could be pretty long, with some reaching up to 40 metres in length.

Finally, the sheets or scrolls were cut to the desired size for specific uses. The standard sheet size could be around 20 by 30 centimetres, but this could vary greatly depending on the intended use.

Preservation

In ancient Egypt, the dry and arid climate naturally preserved documents. Papyrus was often stored in jars or wooden boxes, which provided physical protection from pests and environmental damage.

Ancient Egyptians buried papyrus within the tombs of the dead, which were sealed and protected from the elements. The absence of light, stable temperature, and dry conditions within these tombs also created an environment that aided preservation.

In modern times, where papyrus is no longer kept in jars hidden in sealed underground tombs, several techniques are used to preserve this precious paper. Here are a few of them:

- Temperature and Humidity Control: Often in museums and archives, the preservation of papyrus requires carefully controlled conditions with stable temperature and humidity levels to prevent deterioration.

- Acid-Free Materials: Modern conservation practises involve storing papyrus in acid-free materials to prevent chemical degradation.

- Digital Preservation: High-resolution digital photography and scanning allow for the digital preservation of papyrus, making it accessible to scholars worldwide without the need for physical handling.

- Conservation Techniques: Conservationists use a variety of techniques to stabilise papyrus, such as applying Japanese tissue, a thin but strong paper, to support fragments without obscuring the text.

Discovery

The stories of how these ancient texts have come to light are often as intriguing as the texts themselves. They involve tomb robbers, adventurous archaeologists, and scholars painstakingly piecing together fragments of text like jigsaw puzzles.

Let’s explore some of the most notable papyrus discoveries.

1. The Rosetta Stone

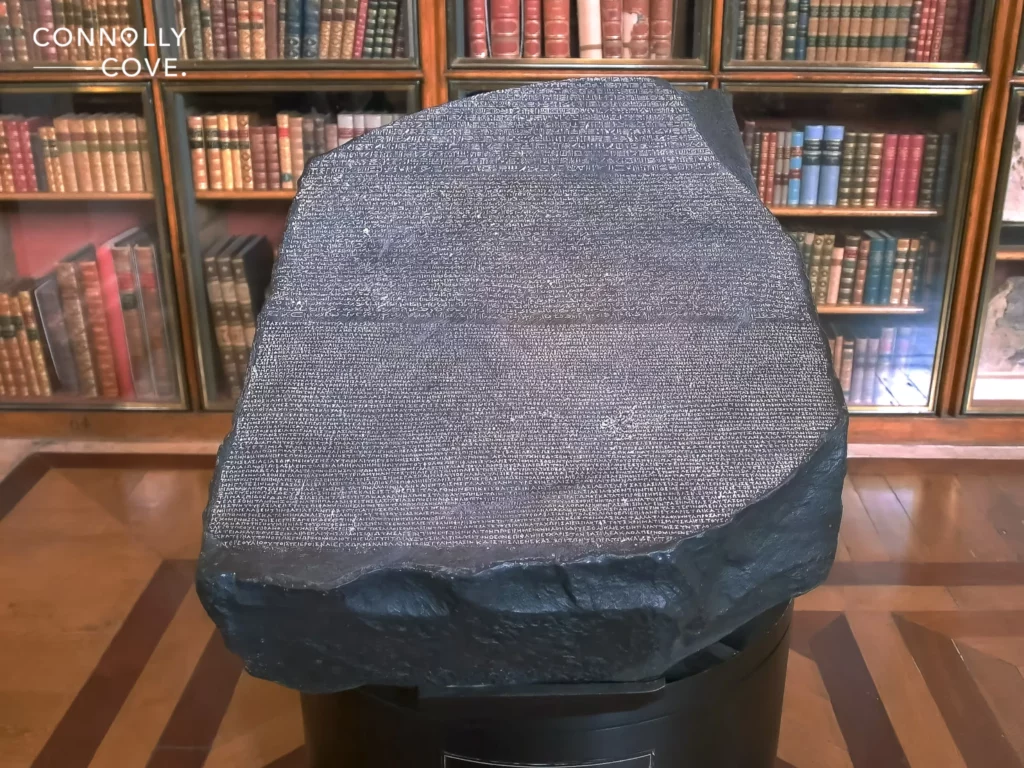

Discovered by chance in 1799 by French soldiers during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt, the Rosetta Stone features a decree inscribed in three different scripts: Greek, Demotic, and hieroglyphic.

While not made of papyrus, the Rosetta Stone was crucial for deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, which allowed scholars to read ancient papyrus texts. In other words, without the Rosetta Stone, we would still be unaware of how significant all those scripted papyrus documents actually are.

2. The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus

Dating back to around 1550 BC, the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus is one of the best sources of Egyptian mathematics. It was initially written by a scribe named Ahmes (or Ahmose) around 1550 BC, though it is thought to be a copy of an even older mathematical text that might date back to the reign of Pharaoh Amenemhat III of the 12th Dynasty.

The Rhind Mathematical Papyrus is named after Alexander Henry Rhind, a Scottish Egyptologist and antiquarian who purchased it in 1858 in Luxor. The papyrus includes arithmetic, algebra, geometry, and a system of linear equations.

3. The Ebers Papyrus

The Ebers Papyrus is among the oldest and most comprehensive medical documents ever found, dating back to around 1550 BC. It includes information on treatments, surgeries, and anatomical observations.

Purchased by Edwin Smith in 1862, this medical papyrus was actually named after the Egyptologist Georg Ebers, who later acquired it.

4. The Edwin Smith Papyrus

The Edwin Smith Papyrus, also bought by Edwin Smith in 1862, is another extensive text on surgery and is dated to the Second Intermediate Period (c. 1600 BC). Remarkably, it features case studies that are thought to be the earliest known examples of medical and surgical science.

Papyrus stands as one of the most outstanding testimonies to Egyptian ingenuity and the desire to record, communicate, and preserve knowledge. From the marshy banks of the Nile to the treasured documents that have withstood the ravages of time, papyrus has served as the canvas for the unfolding of Egyptian history, from the mundane to the divine, and its resilience has allowed future generations a glimpse into the past.

As we continue to uncover papyrus scrolls and fragments, each piece serves as a puzzle in reconstructing our shared history, offering insights not only into the lives of pharaohs and officials but also into the everyday lives of ancient Egyptians.