Exploring Ireland’s Ancient East

Updated On: April 21, 2024 by Ciaran Connolly

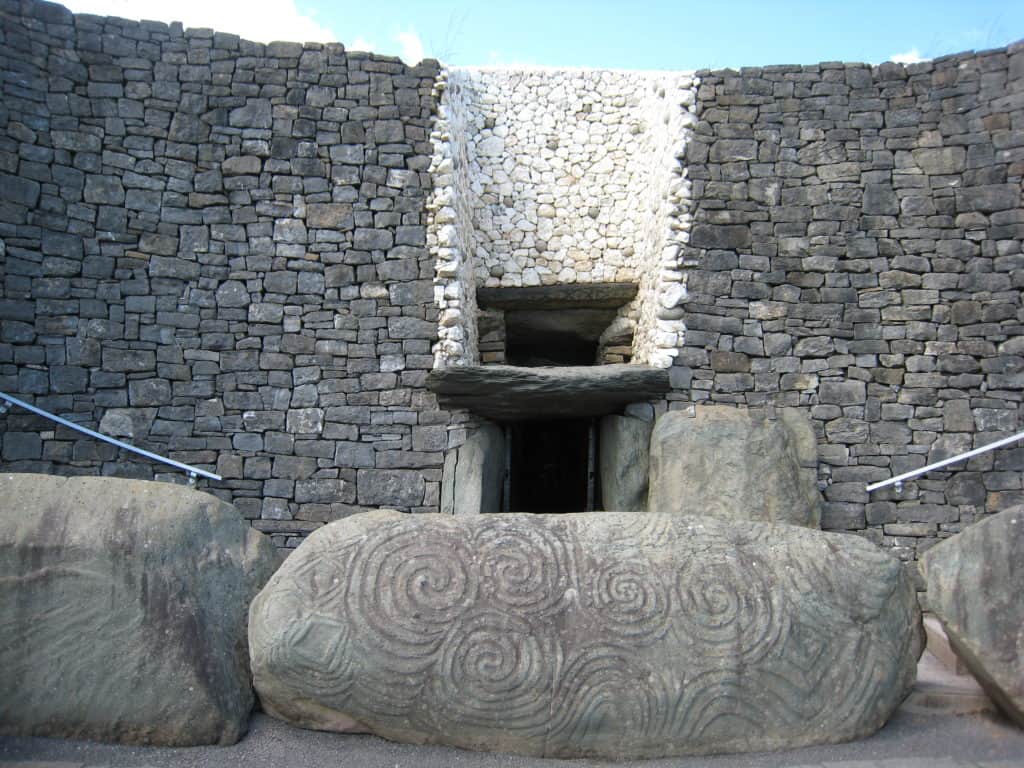

Nestled amongst the rolling hills of Boyne Valley lies Newgrange, a passage tomb constructed by Stone Age farmers over 5,000 years ago. Celebrated by historians as the archaeological jewel of Ireland’s Ancient East, debate continues to surround the neolithic tomb and its mysterious origins. ConnollyCove delves into the inner passages of Newgrange, shining a light on its heritage of myth and mystery.

North of the Boyne, west of Drogheda and central to County Meath, Newgrange stands defiantly in the Irish landscape. The ancient structure represents a victory of human ingenuity, with its walls originally placed around 3200 BC.

Indeed, the passage tomb is yet more remarkable when it is considered that it was constructed over 500 years before the Great Pyramids of Giza and over a millennium before Stonehenge. Notably, Newgrange long-predates the Mycenaean culture of ancient Greece. Now, it is recognised as one of the first advanced civilisations in Europe.

Geological analysis has offered valuable insights into its construction. Research has suggested that the pebbles forming the cairn of Newgrange came from the river terraces of the Boyne, where a large pond at the site is believed to have been quarried for building materials.

Meanwhile, the slabs, kerbstones and rocky facades lining the site have been traced to locations across Ireland; from greywacke sandstone sourced from Clogherhead, County Lough to white quartz cobblestones from the Wicklow Mountains; granodiorite cobbles from the Mourne Mountains; gabbro cobbles from the Cooley Mountains and banded siltstone from Carlingford Lough. It is believed that the majority of these materials were transported uphill to Newgrange via boats at low tide.

Whilst scientific advancement has revealed much about the construction of Newgrange, little is known about the tomb’s purpose, nor the lives of those who conceived and built it. However, it is generally accepted that its builders were native agriculturalists raising cattle and growing various crops in the area surrounding the site.

The effort behind building the structure has itself been disputed. The late geologist and naturalist Frank Mitchell claimed that building would have been achieved within a five-year period. Meanwhile, archaeologist Michael O’Kelly insisted that such a structure would have taken a minimum of thirty years to build.

A Cult of the Dead

Archaeological excavations of the neolithic tomb continue to yield valuable remains and artefacts which shed further light on its uncertain history and purpose. Burnt and unburnt deposits of human bones have been discovered in the passage, with much of the remaining skeletal remains scattered across the tomb.

Further exploration in the 60s and 70s yielded a number of ‘grave goods’ alongside the remains of the dead. Marbles, pendants, beads, flint flakes, bone chisels and many more artefacts were uncovered. The remains of several animals have also been found inside Newgrange, including mountain hares, bats, rabbits and frogs. However, it is accepted that many of these creatures may have entered and died in the chamber centuries, or even millennia, after its construction.

Whilst the exact purpose of Newgrange continues to attract debates, it is generally accepted that it was a site of ceremonial or religious significance throughout various stages of human advancement in Ireland. This was certainly the case for much of the neolithic period where the site appeared to be the focus of much ceremonial activity (a claim supported by the range of artefacts uncovered from this period).

The site had already reached a state of decay and disrepair by 2000 BC, by which point squatters were inhabiting the tomb’s collapsing edge. It is claimed that such squatters were of the Beaker culture imported from mainland Europe and recognised for their unique style of pottery. Indeed, numerous examples of Beaker-era artefacts have been excavated at Newgrange and its surrounding areas.

Examples of later human advancement have been seen in Roman-era jewellery; including bracelets, rings and necklaces. These pieces are now on display at the National Museum of Ireland.

Various indications have led historians and archaeologists to frame Newgrange as a gathering site of a ‘cult of the dead’. Michael O’Kelly, who led excavations of Newgrange in the 60s and 70s, claimed that the passage tombs at the site reflected a veneration of the dead – a core principle of many early European Neolithic religions.

This is a claim supported by the various grave goods which have been uncovered alongside the bodies of the Newgrange dead. However, the concept of Newgrange as a site for ancestral veneration only has been challenged by the structure’s solar-oriented features (for example, the famous ‘light box’ on the roof of the tomb). These features indicate that its architects adhered instead to an astronomically-based faith.

Shining a Light on History

Indeed, the Newgrange architects’ fascination with light is reflected in the chambers, boxes and carvings which adorn the entire structure. Sunlight illuminates the passage through the roof box, aligning in such a way that the light strikes the ground of the inner chamber. Scientific research has determined that the light would have filled the chamber at the precise moment of sunrise, in what is an astonishing level of accuracy.

This is accentuated once a year at the Winter Solstice where the rising sun illuminates the inner chamber, highlighting the carvings inside for approximately 17 minutes. Nowadays, visitors accessing to witness the Winter Solstice at Newgrange are determined by a free lottery where seven lucky visitors are selected at random to observe the illumination.

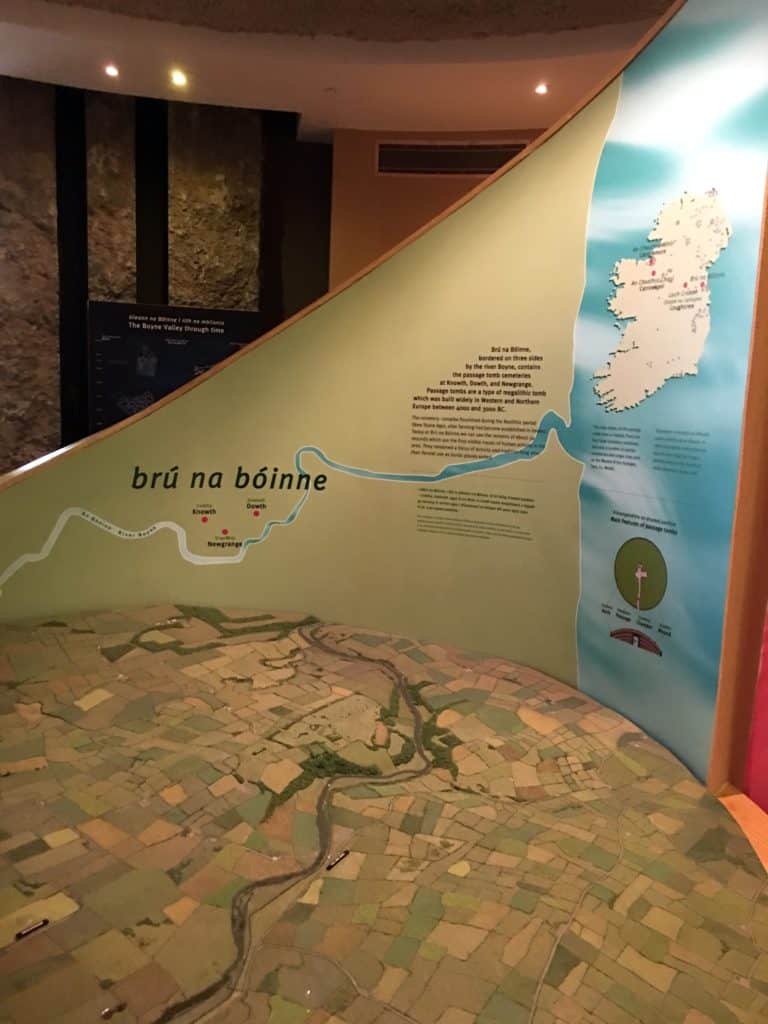

A prevailing theory of Newgrange’s purpose has centred around the Winter Solstice. It has been suggested that the inner chamber was specifically designed for a ritualistic capturing of the sun’s rays on what is the shortest day of the year, potentially signalling a move towards longer days and darker nights. This is an argument supported by similar calendrical and astronomical devices at monuments across the valleys of the Boyne, including Dowth, Knowth and the Lough View Cairns.

Indeed, Newgrange is one of the few structures in Europe to exhibit a roof box feature, alongside Carrowkeel Megalithic Cemetary and Bryn Celli Ddu. Michael O’Kelly was to insist that Newgrange should be observed in relation to the nearby sites of Knowth and Dowth, which similarly stand as monuments to what are now understood to be early-Neolithic religions.

A Resting Place of Kings

Whilst the historic and religious roots of Newgrange remain a source of debate, the site has contributed much to mythology and folklore across Ireland. Many tales of the site and the wider Brú na Bóinne Neolithic were borne out of the medieval period when the monuments of Boyne Valley were said to be the residence of the Tuatha De Danann, a supernatural race in Irish mythology that represented the main deities of pre-Christian Gaelic Ireland.

Newgrange was singled out amongst the Boyne monuments as the home of The Dagda, the most powerful of the Tuatha, as well as that of his wife, Boann, and his son, Oengus.

Folklore surrounding Newgrange and the monuments of Boyne valley can also be traced to The Great Book of Lecan, a manuscript written between 1397 and 1418 in Castle Forbes, close to Enniscrone, Country Sligo. Written in Middle Irish, the manuscript describes how the Dagda built the monuments for use by his family.

Meanwhile, The Book of Leinster (dated 1160) describes a cunning Oengus, who tricks his father into granting him the Brú until the end of time. Later in history, The Pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne (dated 16th century), Oengus takes his friend Diarmuid to the Brú when he again asserted his ownership over the area.

Meanwhile, other storytellers described the mounds of the Boyne to be the burial mounds of the ancient kings of Tara. A national kingship wasn’t a reality in early Irish history. Nonetheless, Kings of Tara represented both prehistoric and mythical ideals of sacred kingship, with future High Kings of Ireland frequently claiming the title of King of Tara.

Local folklore suggested Newgrange and the Boyne monuments as the resting place of the mythological Kings of Tara. Examples of these may have included Cormac mac Airt, Conn of the Hundred Battles and Crimthann Nia Náir.

Protecting Prehistory

Newgrange and its surrounding monuments have been celebrated as some of the best-preserved Neolithic monuments standing in Europe today. However, that status has come as a result of substantive efforts to conserve and reconstruct the ancient monument.

Archaeological interest in Newgrange took off in 1699 when a local landowner ordered his farm workers to dig up a section of the structure. These farmworkers quickly discovered an entrance to the tomb that attracted the attention of Edward Lhwyd, a Welsh antiquarian who wrote the first accounts of the mound, noting the presence of bones and beads inside the tomb.

Following the study by Edward Lhwyd, Charles Campbell, the landowner responsible for Newgrange, noted the discovery of two human corpses. This was to attract the attention of a number of notable antiquarian visitors, including Sir Thomas Molyneaux, Sir William Wilde, George Petrie and James Ferguson.

Newgrange’s earliest antiquarian visitors were to carry out their own studies and measurements of the monument, often providing their own incorrect theories as to its origin. Notably, these intellectual visitors were often dismissive of the idea that the Irish built Newgrange themselves. Invading Vikings, ancient Indians, ancient Egyptians and even the Phoenicians were proposed as architects of the structure. Further evidence and excavation proved all of these theories to be incorrect: the Irish were indeed the builders of Newgrange.

Conservation and Excavation

Sadly, state-led and governmental efforts to protect and preserve Newgrange were not enshrined into legislation until 1882, following the belated passage of the Ancient Monuments Protection Act, which also granted protected status for the nearby monuments of Dowth and Knowth.

Eight years later, a newly-established Board of Public Works, led by Thomas Newenham Deane, began a project of conservation on the monument, which had been extensively damaged over millennia. Furthermore, vandalism over the centuries saw local names engraved on the stones around the structure.

Despite the excavations and research encouraged by the project, researchers and archeologists continued to suggest that Newgrange was built in the Bronze Age, rather than the Neolithic period which came earlier.

The decades which followed saw extensive excavations of the site which were to progress to light installations; bulbs were fitted along the structure’s inner passage illuminating the site for visiting tourists. This was followed by the most exhaustive period of excavation, led by the previously-mentioned Michael J. O’Kelly, leading to the landmark 1982 publication, Newgrange: Archaeology, Art and Legend.

Whilst O’Kelly’s study stood at loggerheads with the findings of his predecessors, most on Newgrange’s antiquarian visitors were to agree on the imposing appearance of the monument: P. R. Griot described the structure as looking like a “cream cheesecake with dried currants distributed about”, whilst Neil Oliver described rebuilt elements of the structure as “a bit brutal, a bit overdone, kind of like Stalin does the Stone Age”.

Visiting Ireland’s Ancient East

Newgrange, Knowth and Dowth can all be found within Ireland’s ancient Boyne Valley, roughly 5.2 miles west of Drogheda, County Meath.

The site’s interpretive centre is located on the south bank of the River Boyne, with Newgrange being located on the north side of the river. Please bear in mind that access to Newgrange is only possible via the interpretive centre.

Access to Newgrange is via guided tours only. Tours begin at the Brú na Bóinne Visitor Centre, from which visitors are taken to the site in groups.

Newgrange Opening Times

- February – April: Daily 9.30am – 5.00pm

- May: Daily 9.00am – 6.30pm

- June – Mid September: Daily 9.00am – 7.00pm

- Mid-Late September: Daily 9.00am – 6.30pm

- October: Daily 9.30am – 5.30pm

- November – January: 9.00am – 5.00pm

*Entrance Gates will be closed 15 minutes after these times.

Admission Fees

A: Exhibition (1hr)

- Adult: €4.00

- Sen/Group: €3.00

- Child/Student: €3.00

- Family: €10.00

B: Exhibition and Newgrange (2hrs)

- Adult: €7.00

- Sen/Group: €6.00

- Child/Student: €4.00

- Family: €16.00

C: Exhibition and Knowth (2hrs)

- Adult: €6.00

- Sen/Group: €4.00

- Child/Student: €4.00

- Family: €14.00

D: Exhibition, Newgrange and Knowth (3hrs)

- Adult: €13.00

- Sen/Group: €10.00

- Child/Student: €8.00

- Family: €30.00

The Boyne Valley contains some of Ireland’s most treasured sites. For more stories of Ireland’s hidden history, visit ConnollyCove: Ireland’s leading travel and tourism blog.