Dame Kathleen Lonsdale: Irish Scientist, Reformer, and Educator

Updated On: April 07, 2024 by Noha Nabil

Dame Kathleen Lonsdale (née Yardley) (1903 – 1971) was an Irish scientist specialising in Crystallography, a passionate prison reformer, and a Quaker pacifist.

Kathleen was born in Newbridge, County Kildare, to Harry Yardley and Jessie Cameron. She was the couple’s tenth and youngest child. Her parents had an exceedingly unhappy relationship due to their constant financial problems, which kept them constantly on the verge of poverty, Harry’s severe alcoholism, and the deaths of four of their children, which ripped a hole in the relationship that couldn’t be filled. Although she and her siblings had a complicated relationship with their father, Kathleen later commented that she inherited her passion for facts from her father’s extensive reading habit.

When Kathleen turned five, her parents split up, and her mother moved Kathleen and her siblings to Seven Kings in Essex, England. As her mother was a staunch Baptist Christian, much of Kathleen’s childhood was spent in church.

Kathleen studied at Woodford County High School for Girls in East London before being transferred to their sibling school, Ilford County High School for Boys, to study maths and science, for the all-girls school did not offer STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) subjects as they were not considered suitable career paths for women. Her siblings did not stay at school because the family’s dire financial situation did not allow for it; Kathleen’s elder brother Fred became a wireless operator and had his place in history as the operator to receive the last signals from the ill-fated Titanic in 1912.

She excelled in school, achieving distinctions in six subjects, and was accepted at Bedford College for Women at sixteen. She specialised in physics, achieved the highest scoring grades in ten years, and graduated with a BA in Science in 1922. She studied physics at University College London, graduating with an MSc in 1924. Kathleen proved her former headmistress wrong, for she had been weary of Kathleen’s decision to go into this particular area of science; she believed it was doomed because Kathleen would “never distinguish herself in physics”.

Career and Research of Kathleen Lonsdale

Kathleen’s intelligence was noted by the English physicist (the innovator of X-ray diffraction), chemist, mathematician, and sportsman Sir William Henry Bragg. He invited Kathleen to join his research school at University College and the Royal Institution, London. Of Bragg, Kathleen later said, “He inspired me with his love of pure science and with his enthusiastic spirit of enquiry and at the same time left me entirely free to follow my line of research”.

Kathleen was gifted in many areas, but Bragg encouraged her to focus on crystallography. Kathleen’s friend and colleague Dorothy Hodgkin, the 1964 chemistry Nobel laureate, said of her: “There is a sense in which she appeared to own the whole of crystallography in her time”.

Crystallography, explains CSIC’s Department of Crystallography and Structural Biology, is “a branch of science that examines crystals. Today, we know that crystals are made of matter, atoms, molecules and ions that fit together in repeating patterns, called unit cells, which form the crystals like bricks stacked in three dimensions. Inside the unit cells, atoms are also repeated by symmetry operations. These patterns cause the crystals to show many sorts of unique shapes that, for thousands of years, have drawn our attention for their colours and outer beauty. With the crystallographic tools developed during the 20th century, we can find out the inner structure of matter, living or inanimate, from which crystals are formed. Knowing the inner structure of matter means determining the positions of all atoms and how they are linked together, in many cases forming atomic clusters known as molecules. The atomic structure of matter generates knowledge used by chemists, physicists, biologists, and other scientists. This allows us to understand the properties of matter and modify them for our benefit”.

Kathleen was the only woman on Bragg’s research team. The post provided her with £180 per month, greatly assisting her financial situation and enabling her to support her mother and siblings. Kathleen’s first significant publication was the International Tables, better known as the ‘crystallographer’s bible’, which were comprehensive tables for ascertaining crystal structure.

Kathleen married Thomas Jackson Lonsdale in 1927 and had three children: Jane, Nancy, and Stephen. Thomas, an engineering student, was incredibly supportive of Kathleen’s work. Kathleen moved with him when he was appointed a position at the Silk Research Association in Leeds. She worked on X-ray diffraction at the University of Leeds’ Department of Physics. Soon, the couple returned to London. Thomas worked on experiments for his PhD, and Kathleen stayed at home briefly to raise her children. She remained passionately dedicated to her work and pursued research at home, focusing primarily on calculating structure factors.

Kathleen made her first significant discovery in 1929. According to RTE, Kathleen answered “an important question that scientists had been arguing over for sixty years: she demonstrated conclusively that the benzene ring was flat”. This was a crucial breakthrough in organic chemistry. Kathleen also established herself through her application of the Fourier method (a system of representing arbitrary signals as weighted sums of complex sinusoids), which she used for the first time to analyse X-ray patterns in solving the structure of hexachlorobenzene.

According to Britannica, Kathleen also “developed an X-ray technique with which she obtained an accurate measurement (to seven figures) of the distance between carbon atoms in diamond. She also applied crystallographic techniques to medical problems, particularly the study of curare-like drugs and bladder stones”.

Braggs was keen to get Kathleen back to University College London, and in 1931, he wrote to inform her that he had “a piece of good news! Sir Robert Mond is giving me £200 with which you are to get assistance at home to enable you to come and work here”. Kathleen returned and remained a part of Braggs’ team for fifteen years. She was awarded a DSc by University College London in 1936.

In 1945, Kathleen became one of the first two women to be elected a Fellow of the Royal Society, a society over 300 years old, and in 1949, she was appointed professor of chemistry and head of the Department of Crystallography at University College London. She was also the first tenured woman professor at that college, a position she held until 1968 when she was named Professor Emeritus, a title “bestowed on all professors who have retired in good standing”.

In 1955, a rare form of hexagonal diamond was named Lonsdaleite in Kathleen’s honour. Of the experience, she commented: “It makes me feel both proud and rather humble […] the name seems appropriate since the mineral only occurs in tiny quantities … and it is generally rather mixed up!”

Kathleen’s publications were highly influential in her field, especially Simplified Structure Factor and Electron Density Formulae for the 230 Space Groups of Mathematical Crystallography, “Divergent Beam X-ray Photography of Crystals,” in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, and Crystals and X-Rays. Kathleen also received several honours throughout her career, including being elected an Honorary Member of the Women’s Engineering Society in recognition of her “brilliant and important work” in 1946, being selected as the first woman president of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1967, and an Honorary Degree (Doctor of Science) by the University of Bath in 1969.

There are also numerous buildings named after her at University College, London, University of Limerick, and Dublin City University. A plaque was erected at the Lonsdale family home in Newbridge in 2003 by the National Committee for Commemorative Plaques in Science and Technology, 100 years after her birth.

A feminist in every sense of the word, Kathleen sought to encourage and support women who wanted to embark upon a scientific career and raise a family. According to ChemistryWorld, in 1970, Kathleen said: “Any country that wants to make full use of all its potential scientists and technologists could do so, but it must not expect to get the women quite so simply as it gets the men… Is it Utopian, then, to suggest that any country that wants married women to return to a scientific career when her children no longer need her physical presence should make special arrangements to encourage her to do so?”

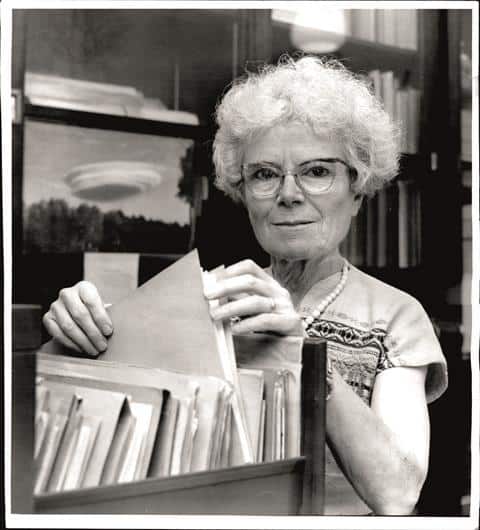

Dame Kathleen

Source: Financial Times

Pacifism and Prison Reform

Kathleen and her husband Thomas became Quakers in 1935. Already sponsors of the UK-based Peace Pledge Union, a non-governmental organisation that promotes pacifism, the couple were attracted to the religion’s genuine commitment to pacifism, equality and justice, peace, truth and integrity, and simplicity and sustainability.

According to Quakers of Britain, the religion “doesn’t offer neat creeds or doctrine. Instead, we try to help each other work out how we should live. All people are welcome and accepted at a Quaker meeting. Quakerism is almost 400 years old. It’s the common name for the Religious Society of Friends. It grew from Christianity; today, we find meaning and value in other faiths and traditions. We recognise that there’s something transcendent and precious in every person. Different Quakers use different words to describe this, but we all believe we can be in contact with it and encounter something beyond ourselves”.

Kathleen was well-respected by the Quaker community; she delivered the keynote speech – Removing the Causes of War – at the British Quakers’ annual meeting in 1953. Is Peace Possible?, one of her most renowned, non-scientific books, is driven by Quaker sentiments and cites Martin Luther King’s “non-violent civil rights movement, and – as co-founder of the Pugwash Movement and the Atomic Scientists’ Association – warns of the danger of nuclear weapons and the problems presented by the disposal of nuclear waste”. Her work on peaceful dialogue was rewarded with the appointment of the first secretary of the Churches’ Council of Healing by the Archbishop of Canterbury William Temple.

Throughout her life, Kathleen travelled around the UK, Russia, and China promoting peace. She was the vice president of the Atomic Scientists Association and the president of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. She was a crucial figure in the Pugwash Movement, an organisation designed to “bring together scholars and public figures to work toward reducing the danger of armed conflict and to seek solutions to global security threats”.

Kathleen’s interest in prison reform was sparked during the Second World War. British citizens were expected to sign up for civil defence/war service. A committed pacifist, Kathleen refused and was fined £2. Principled to her core, Kathleen refused to pay and was jailed for one month at Holloway Prison. Although she could continue her scientific work, she was also required to clean and do various other jobs required by the prison system.

Upon leaving, Kathleen became a committed prison reform activist. Of her experience in prison, she said, “What I was not prepared for was the general insanity of an administrative system in which lip service is paid to the idea of segregation and the ideal of reform, when in practice the opportunities for contamination and infection are innumerable, and those responsible for re-education practically nil”. Kathleen joined the Howard League for Penal Reform and frequently visited women in prison as a form of support.

Kathleen passed away in 1971 from anaplastic cancer at the relatively young age of 68. She is remembered for her scientific discoveries, craving for a space for women in STEM fields, and her dedication to peace.

Conclusion

Dame Kathleen Lonsdale’s life and work exemplify the intersection of scientific excellence, social activism, and educational leadership. From her groundbreaking research in crystallography to her advocacy for women’s rights and prison reform, she left an indelible mark on the world, challenging conventions and championing causes transcending disciplinary boundaries.

As we celebrate her contributions and legacy, let us also heed her call to action—to strive for a world where knowledge knows no bounds, where opportunity is accessible to all, and where compassion and justice prevail. In honouring the memory of Dame Kathleen Lonsdale, we celebrate not only a pioneering scientist and reformer but also a beacon of hope and inspiration for generations to come.