The Extraordinary Irish Giant: Charles Byrne

Updated On: November 07, 2023 by Ciaran Connolly

Gigantism, or giantism, is a rare medical condition characterised by excessive height and growth significantly above average human height. While the average human male is 1.7m tall, those suffering from gigantism tend to average between 2.1 m and 2. 7, or between seven and nine feet. Remarkably few people suffer from this rare condition, but one of the most famous cases – Charles Byrne – hails from Ireland.

Gigantism is caused by abnormal tumour growths on the pituitary gland, a gland at the base of the brain that secretes hormones directly into the blood system. Not to be confused with acromegaly, a similar disorder that develops during adulthood and whose major symptoms include enlargement of the hands, feet, forehead, jaw, and nose, thicker skin, and deepening of the voice, gigantism is obvious from birth and excessive height and growth develops before, during and puberty, and continues into adulthood. Health problems often accompany the disorder and can range from excessive damage to the skeleton to increased strain on circulatory systems, often resulting in high blood pressure. Unfortunately, the mortality rate for gigantism is high.

Charles Byrne: The Irish Giant

Charles Byrne was born and grew up in a small town called Littlebridge on the borders of County Londonderry and County Tyrone, Northern Ireland. His parents were not tall folk, one source revealing that Byrne’s Scottish mother was a “stout woman”. Charles’s unusual height inspired a rumour in Littlebridge that his parents conceived Charles on top of a haystack, accounting for his uncommon condition. His excessive growth started to bother Charles Byrne during his early school days. Eric Cubbage stated he soon outgrew not only his peers but all the adults in the village, and that “he was always drivelling or spitting and the other boys would not sit beside him, and he was very much troubled with pains (‘growing pains’).”

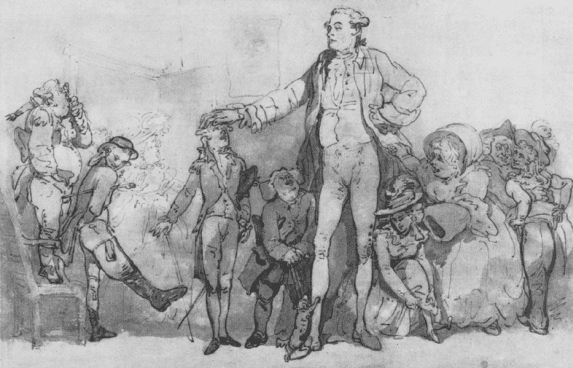

Tales of Charles Byrne began to circulate throughout the counties and soon he was scouted by Joe Vance, an innovative showman from Cough, who convinced Charles and his family that this could be of benefit to them. Marketed correctly, Charles’s condition could bring them fame and fortune. Vance wished for Charles Byrne to be a one-man curiosity or travelling freak show at various fairs and marketplaces around Ireland. How enthusiastic Charles was about Vance’s proposal is unknown, but he agreed and soon Charles Byrne was famous throughout Ireland, attracting spectators by the hundreds. Wishing to take advantage of the general public’s curiosity for unusual and the macabre, Vance took Charles to Scotland, where it is said that Edinburgh’s “night watchmen were amazed at the sight of him lighting his pipe from one of the streetlamps on North Bridge without even standing on tiptoe.”

Charles Byrne in London

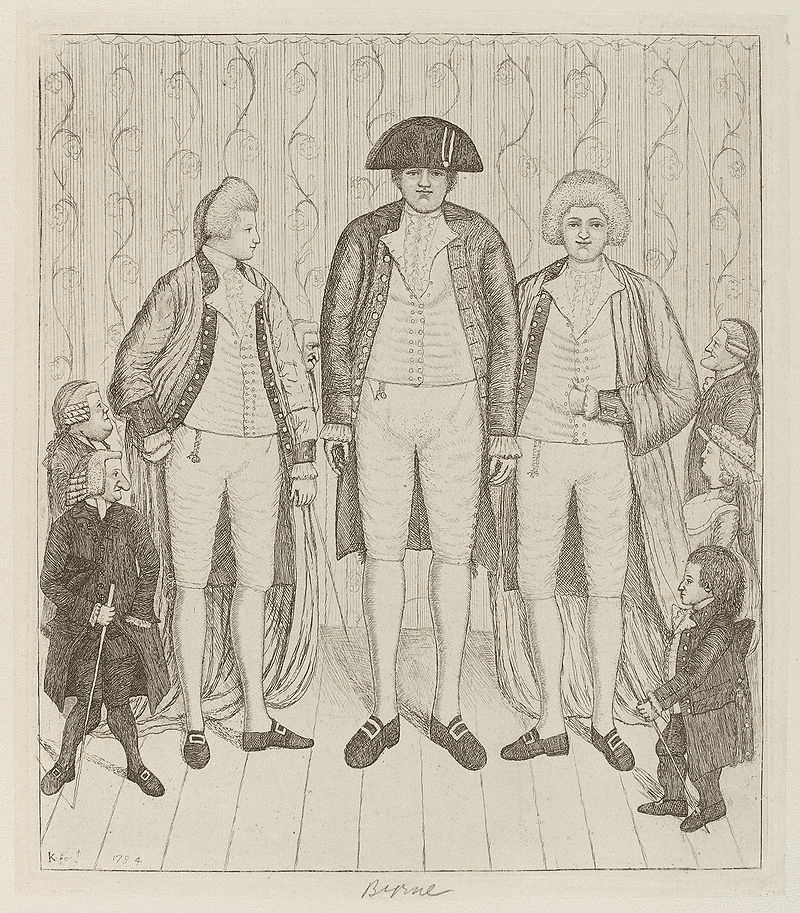

From Scotland they progressed steadily through England, gaining more and more fame and fortune before arriving in London in early April 1782, when Charles Byrne was 21. Londoners looked forward to seeing him, advertising his appearance in a newspaper April 24th: “IRISH GIANT. To be seen this, and every day this week, in his large elegant room, at the cane shop, next door to the late Cox’s Museum, Spring Gardens, Mr Byrne, he surprising Irish Giant, who is allowed to be the tallest man in the world; his height is eight feet two inches, and in full proportion accordingly; only 21 years of age. His stay will not belong in London, as he proposes shortly to visit the Continent.”

He was an instant success, as a newspaper report published a few weeks later reveals: “However striking a curiosity maybe, there is generally some difficulty in engaging the attention of the public; but even this was not the case with the modern living Colossus, or wonderful Irish Giant; for no sooner was he arrived at an elegant apartment at the cane shop, in Spring Garden-gate, next door to Cox’s Museum, than the curious of all degrees reported to see him, being the sensible that a prodigy like this never made its appearance among us before; and the most penetrating have frankly declared, that neither the tongue of the most florid orator, or pen of the most ingenious writer, can sufficiently describe the elegance, symmetry, and proportion of this wonderful phenomenon in nature, and that all descriptions must fall infinitely short of giving that satisfaction which may be obtained on a judicious inspection.”

Charles Byrne was such a success that he was able to move into a beautiful and expensive apartment in Charing Cross and then to 1 Piccadilly before finally settling back in Charing Cross, at Cockspur Street.

According to Eric Cubbage, it was Charles Byrne’s gentle giant persona that attracted spectators the most. He explains that Charles was: “elegantly dressed in a frock coat, waistcoat, knee breeches, silk stockings, frilled cuffs and collar, topped by a three-cornered hat. Byrne spoke graciously with his thunderous voice and displayed the refined manners of a gentleman. The giant’s large, square jaw, wide forehead, and slightly stooped shoulders enhanced his mild disposition.”

A Change in Fortune: The Decline of Charles Byrne

Things soon turned sour, however. Charles Byrne’s popularity began to fade – notably, this seemed to correlate with his presentation before the Royal Society and his introduction to King Charles III – and spectators began to express boredom towards him. A prominent physician at the time, Sylas Neville, was decidedly unimpressed with the Irish Giant, noting that: “Tall men walk considerably beneath his arm, but he stoops, is not well-shaped, his flesh is loose, and his appearance far from wholesome. His voice sounds like thunder, and he is an ill-bred beast, though very young –only in his 22nd year.” His rapidly failing health and rapidly falling popularity drove him to excessive consumption of alcohol (which only exacerbated his ill-health for it is believed that he contracted tuberculosis around this time).

Charles Byrne’s fortunes turned when he decided to place his wealth into two singular banknotes, one was worth £700 and the other £70, which he carried on his person. Although it is unknown why Charles thought this was a safe idea, he likely thought no-one would dare rob a man of his stature. He was wrong. In April 1783, a local newspaper reported that: “’The Irish Giant, a few evenings since taking a lunar ramble, was tempted to visit the Black Horse, a little public-house facing the King’s mews; and before he returned to his apartments, found himself a less man than he had been the beginning of the evening, by the loss of upwards of £700 in banknotes, which had been taken out of his pocket.”

His alcoholism, tuberculosis, the ever-constant pain his continuously growing body caused him, and the loss of his life’s earnings sent Charles into a deep depression. By May 1783, he was dying. He was suffering from intense headaches, sweating and constant growth.

It was been reported that while Charles did not fear death itself, he was fearful of what surgeons would do to his body once he died. It was reported by his friends that he begged them to bury him at sea so body snatchers could not exhume and sell his remains (body snatchers, or resurrection men, were a particularly pesky problem in the late 1700s, right up to the late 1800s). It seems that Charles did not mind being considered a ‘freak’ when he consented to it, but the idea of being displayed or dissected against his will caused him tremendous emotional and mental turmoil. Charles also came from a religious background that believed in the preservation of the body; without his body intact, he believed, he would not get into Heaven come Judgement Day.

After Death: Dr John Hunter

Charles died on June 1st 1783, and he did not get his wish.

Surgeons “surrounded his house just as Greenland harpooners would an enormous whale”. A newspaper reported: “so anxious are the surgeons to have possession of the Irish Giant, that they have offered a ransom of 800 guineas to the undertakers. This sum if being rejected they are determined to approach the churchyard by regular works, and terrier-like, unearth him.’

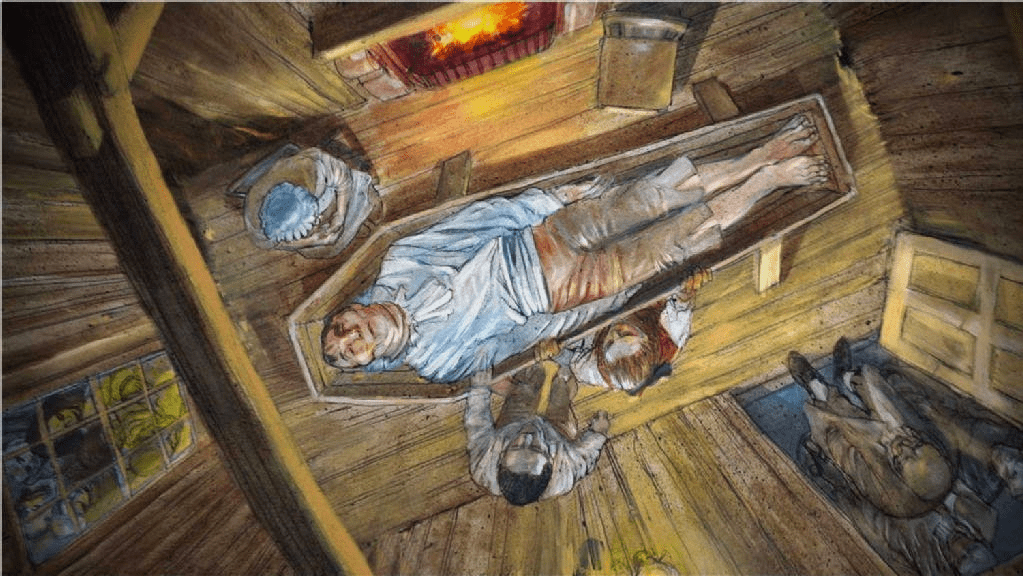

To avoid what fate had in store for him, Charles, according to Cubbage, made “specific arrangements to protect his body from the prying hands of the anatomists. After his death, his body was to be sealed in a lead coffin and to be watched day and night by his loyal Irish friends until it could be sunk deep in the sea, far from the grasp of his pursuers. Using what remained from his life savings, Byrne prepaid the undertakers to ensure that his will be carried out.” The coffin’s measurements were eight feet, five inches inside, the outside nine feet, four inches, and the circumference of his shoulders s three feet, four inches.

Charles’s friends organised a sea burial at Margate, but it was discovered years later that the body inside the coffin was not their friend. The undertaker responsible for Charles’s body secretly sold it to Dr John Hunter, reportedly for a widely substantial amount of money. While Charles’s friends were drunk, on their way to Margate, heavy paving stones from a barn were placed in the lead coffin and sealed, and Charles’s body was taken back to London without their knowledge.

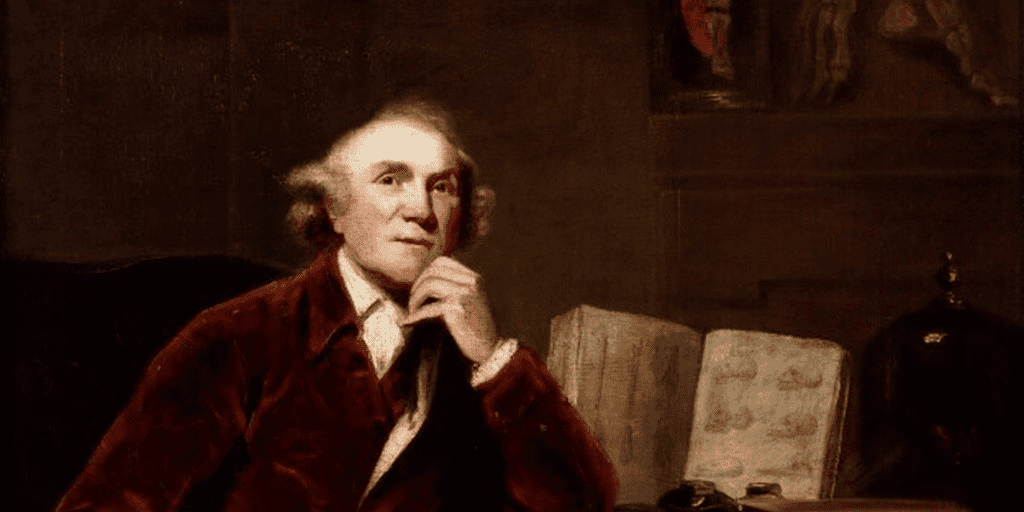

Hunter was London’s most distinguished surgeon at the time, and he was known as the “Father of Modern Surgery”, the knowledge and expertise for which he gained through dissecting bodies brought to him by body snatchers. It is said that Hunter, among his scientific interests, was also a lover and collector of items outside the normal realms of nature, so it is likely he wanted Charles’ body for more than just gaining scientific knowledge. Hunter had seen Charles at one of his exhibition shows and Hunter became obsessed with obtaining him. He employed a man by the name of Howison to watch Charles’ whereabouts up until his death, so he would be the first to claim him.

Supposedly, Hunter was wary of the repercussions he would face should Charles’s friends and family discover what happened to him, so he chopped Charles’s body up and boiled the pieces in a copper tub until nothing but bones remained. Hunter waited four years until Charles’s notoriety in the public eye had faded completely, before assembling Charles’s bones and displaying them in his museum, the Hunterian Museum, located in the building of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

Where is Charles Byrne now?

Charles’s bones remain at the Hunterian Museum, his requests for a burial at sea going unheeded and unhonoured for over 200 years. Legend has it that when you approach his glass display case, you can hear him whisper “let me go”.

Charles’s bones are one of the museum’s top attractions, and they received tremendous after 1909, when American neurosurgeon Henry Cushing examined Charles’s skull and discovered an anomaly in his pituitary fossa, enabling him to diagnosis the particular pituitary tumour that caused Charles’s gigantism.

In 2008, Márta Korbonits, a professor of endocrinology and metabolism at Barts and the London NHS Trust, became fascinated by Charles and wished to determine if he was the first of his kind or if his tumour was a genetic inheritance from his Irish ancestors. After being granted permission to send two of his teeth off to a German lab, which is mostly used to extract DNA from recovered sabre-toothed tigers. It was eventually confirmed that both Byrne and today’s patients inherited their genetic variant from the same common ancestor and that this mutation is some 1,500 years old. According to The Guardian, “the scientists’ calculations show that some 200 to 300 living people might be carrying this same mutation today, and their work makes it possible to trace carriers of this gene and treat patients before they grow to be a giant.”

The giants of Irish legend may not be a legend after all, but an indisputable scientific fact.