Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu: Father of the English Ghost Story

Updated On: November 07, 2023 by Ciaran Connolly

Joseph Thomas Sheridan Le Fanu (28th August 1814 – 7th February 1873) was a prolific Irish-born writer best known for his 1872 gothic vampire novel Carmilla. He is considered to be one of the most influential figures in nineteenth-century gothic literature. A writer of gothic horror and mystery tales, as well as a keen journalist, his work has been praised for its psychological insight, evocative physical descriptions, and compelling and realistic use of the supernatural. Le Fanu was a writer who explored “the equilibrium between the natural and the supernatural” and was deemed by fellow gothic writer M. R. James to be “absolutely in the first rank as a writer of ghost stories.”

Le Fanu’s Early Life

Le Fanu was born in Dublin to a literary French Protestant family of English and Irish descent. He was the middle child of Irish Dean Thomas Phillip Le Fanu and Charles Orpen biographer Emma Lucretia Dobbin, and he had many relatives who wrote, including his grandmother Alicia and great-uncle Richard, who were both playwrights.

Shortly after Le Fanu’s birth, the family relocated to Dublin’s Royal Hibernian Military School when his father was appointed as the institution’s chaplain. This role requires clergymen to work in and with places outside the regular congregation setting, and are usually a government-funded space, such as schools, prisons, and hospitals. The Royal Hibernian Military School was located in Phoenix Park and adjacent to the small village of Chapelizod, whose church would feature in Le Fanu’s later work. The family did not remain there for long and soon relocated again to the civil parish of Abington, which lies partly in County Limerick and County Tipperary. This exposure to Ireland’s rural life and its rich folklore tradition made a lasting impression on Le Fanu and would greatly influence his writing.

Le Fanu and his siblings did not attend public school and were instead taught by a tutor (a common occurrence for families of church employees). The siblings did not get along with the tutor, and the tutor was often criticised by Le Fanu’s brother William of teaching them “nothing”. When the tutor was dismissed, Le Fanu relied on his father’s private library for his education, and by the age of fifteen was regularly writing poetry. Although he shared his work with his mother and siblings, he hid this talent from his father who, as a strict Protestant minister with Calvinist leanings, would have opposed such creative practices.

The Le Fanu’s relocated for a third time back to Dublin after Abington was affected by the Tithe War, a mostly peaceful civil unrest regarding tithe payments, compulsory tax payments, to the Catholic Church of Ireland.

(Source: The National Library of Ireland)

University & Marriage

Le Fanu’s father struggled constantly with financial debt. The tension over the rising rejection of tithes in Ireland meant that his father had to regularly travel to the south of Ireland for work, which kept the family afloat for a while, but it was ultimately a short-term solution. In 1833, Le Fanu’s father had no funds to visit his dying sister in Bath, England (herself in debt due to medical bills) and had to borrow money from a cousin, who himself was incarcerated in a debtors prison a few short years later.

Le Fanu knew he was not destined for a life of religious servitude like his father, nor did he wish to repeat a life crushed by financial debt, so he studied Classics at Trinity College in Dublin. Le Fanu thrived at Trinity, becoming the Auditor of the College Historical Society, and contributing regularly to the debating society. Upon completion of his studies, Le Fanu studied Law at King’s Inn in London, but by now he knew his passion lay with the written word. He had published stories regularly with Dublin University Magazine, including his first horror story entitled The Ghost and Bone-Setter in 1838, so rather than taking the Bar exam, Le Fanu embarked upon a career in journalism. Seeing a future in the medium, LeFanu became the owner of several magazines, including the Warder and The Dublin Evening Mail.

Le Fanu married in 1844. His wife, Susanna Bennett, was the daughter of an important Dublin barrister. The couple stayed with Le Fanu’s parents for Christmas that year, which would prove to be his father’s last – Thomas Le Fanu died in 1845. It is unclear whether Thomas lived long enough to meet his granddaughter Eleanor, who was born in1845. Le Fanu and Susanna went on to have three more children: Emma (born 1846), Thomas (born 1847, likely named for his grandfather) and George (1854).

Although most of his work focused on writing, particularly ghost stories, Le Fanu was also politically engaged and highly critical of the Irish government at this time. He was an ardent supporter of Irish Nationalists John Mitchel and Thomas Francis Meagher, who campaigned stringently against the government’s seeming indifference to victims of the Irish Famine.

As a writer, Le Fanu was free to work anywhere, and so, in 1856, moved his family to the home of Susanna’s parents, who had retired to England, in Merrion Square. Le Fanu rented the property from Susanna’s brother (like his father, he often struggled with the rent).

(Source: Find A Grave)

Le Fanu’s Writing Career and Death

All evidence available indicates that Le Fanu and Susanna were a happy couple, but Susanna’s mental health caused tension within the relationship. She was plagued by neurotic symptoms, underwent a crisis of religious faith and began to attend church services St. Stephen’s Church as often as she could, and endured major anxiety after the deaths of close family members, including her father. Tragedy struck in 1858 when Susanna suffered what was described as a “hysterical attack” and died the following day. The exact circumstances remain unclear.

Le Fanu was distraught by her loss – his diaries suggest he was tormented by guilt – and did not write any fiction until after the death of his own mother in 1861. Le Fanu became a recluse for most of his later life and subsequently became known in Dublin as ‘the invisible prince’ (which is etched on his gravestone). He is said to have written only at night, by the light of two candles. Throughout his grieving process, Le Fanu leaned heavily on his cousin Lady Gifford, who would become a life-long confidant and source of encouragement.

1861 marked a significant change in Le Fanu’s writing career. He became the owner and editor of Dublin University Magazine, where he serialised his short stories and published them twice, once in a version for Ireland, and once in a version for England, ensuring more exposure and a wider readership for his work. Two of his most famous works – The House by the Churchyard (1863) and Wylder’s Hand (1864) – were published via this method.

The House by the Churchyard, which was set in Ireland and infused with traditional Irish folktales, received unenthusiastic reviews from his English readers, and upon signing a contract with London publisher Richard Bentley, Le Fanu was advised to make his stories “of an English subject and of modern times”. Bentley’s advice was invaluable to Le Fanu. His next work, a gothic tale set in Derbyshire, and early example of the locked-room mystery, Uncle Silas: A Tale of Bartram-Haugh (1864), was immensely successful. It bolstered his position within English and Irish literary circles as a figure to be respected and admired. Although he stuck to this formula for years, his later work featured more of his folkloric inspirations from his native land of Ireland.

Le Fanu died in 1873, one year after the publication of his most famous novel Carmilla (1872). Le Fanu died of a heart attack and is supposedly said to have “died of fright”, although under what circumstances we do not know. Le Fanu is buried with his wife in Saint Jerome Cemetery in Dublin.

(Source: didweknow)

Le Fanu’s Legacy

Le Fanu was among the first of the nineteenth-century gothic writers to infuse psychological insight with supernatural stories that potentially have a ‘natural’ explanation, though he often left these details a mystery to the reader. Critics have since deduced that Le Fanu’s experience with Susanna’s mental illness enabled him to write with refreshing insight into the mental anguish of his characters. His works, including the short story collection In A Glass Darkly (1872) and novel Uncle Silas (1864), are evidence of this.

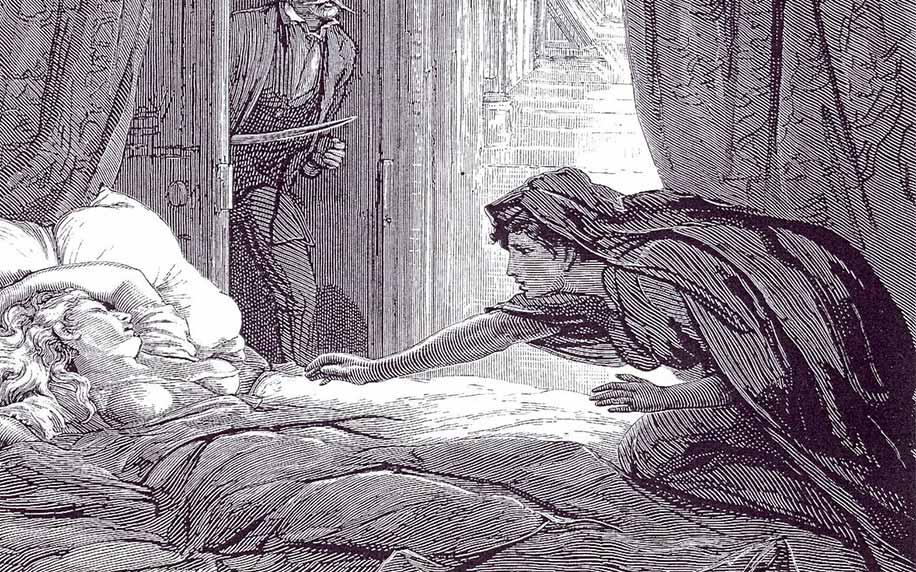

His most enduring work is Carmilla, one of the first long-form English prose vampire stories. First published as a serial in London literary magazine The Dark Blue, it is narrated by Laura, a young woman tormented by a vampiric woman named Carmilla, also known as Countess Karnstein. This work greatly influenced Bram Stoker’s Dracula, published twenty-five years later: both works feature first-person narration, similar physical descriptions (Stoker’s Lucy bears a striking resemblance to Carmilla, both in regards to her appearance and sexuality, once turned) and Le Fanu’s vampire expert Baron Vordenburg is an obvious inspiration for Stoker’s vampire hunter Abraham Van Helsing.

Carmilla is also an early example of a lesbian vampire romance.

“Sometimes after an hour of apathy, my strange and beautiful companion would take my hand and hold it with a fond pressure, renewed again and again; blushing softly, gazing in my face with languid and burning eyes, and breathing so fast that her dress rose and fell with the tumultuous respiration. It was like the ardour of a lover; it embarrassed me; it was hateful and yet overpowering; and with gloating eyes she drew me to her, and her hot lips travelled along my cheek in kisses; and she would whisper, almost in sobs, “You are mine, you shall be mine, and you and I are one for ever.” (Carmilla)

Although the homosexual relationship between the two women is not overtly acknowledged, it is clear from Laura’s narration that a sexual attraction is there, and it becomes a significant part of the tale. This makes Carmilla a crucial part of LGBTQ+ literary history.

Le Fanu’s work may have disappeared into obscurity were it not for the efforts of a fellow gothic ghost story writer, M. R. James. James considered Le Fanu “the master of us all” and dedicated a significant portion of his life to resurrecting love and appreciation for Le Fanu’s work.