Irish Female Scientists You Should Know

Updated On: November 07, 2023 by Ciaran Connolly

Ireland is known for its natural beauty, its rich creative culture, and its tragic history, but it has also produced an astounding number of female scientists. Historically, women’s contribution to the S.T.E.M subjects – science, technology, engineering, and mathematics – has been stunted by the limitations placed on them by patriarchal culture. According to this social construction, a woman’s place is in the domestic sphere, the home, where they are expected to be a good housewife and mother.

These limitations made it difficult for women to make their own way in the world, but the Victorian and Edwardian periods in Ireland produced several intelligent and determined women who made important contributions to science.

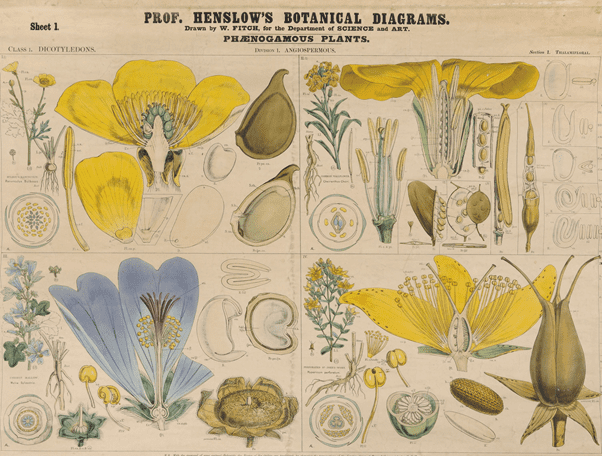

(Source: Nyafuu Archive)

Female Scientists: Botanists

The scientific study of the physiology, structure, genetics, ecology, distribution, classification, and economic importance of plants.

Ellen Hutchins (1785 – 1815)

Ellen Hutchins was one of Ireland’s early botanists, predating the contributions Victorian scientists, who specialised in the study of seaweed, lichens, mosses and liverworts. Born in Ballylickey, County Cork, Ellen was a sickly child who suffered from a variety of illnesses, more than likely exacerbated by her father’s untimely death when she was two years old, and being underfed as it was considered unladylike for women to eat the same portions as men. To improve her health, she briefly lived with a family friend and doctor Whitley Stokes, who encouraged her to pursue a study of natural history as part of her healing process. When her health improved, Ellen moved home to care for her mother and disabled brother.

Her time with Stokes inspired a love of botany, Stokes’s own speciality, so Ellen began to identify, record, and produce detailed drawings and watercolours of the plants she collected in the Bantry area and County Cork. She was particularly fascinated by cryptogams – plants that reproduce via spores rather than seeds – including seaweed and moss, which was an unresearched area of botany in the early 19th century.

Ellen acquainted herself with fellow botanists, including James Townsend Mackay, who respected her natural ability to find and accurately identify cryptogams and remained close to Stokes, to whom she sent specimens and documentation of her latest findings. Her work was often published by her peers, and although she initially resisted having her name associated with her findings, she eventually relented. Plants named after her include pertusaria hutchinsiae, cladophora hutchinsiae, and dasya hutchinsiae.

Her health began to fail her in the 1810s, and by 1812 she was gravely ill. She died in February 1815, shortly before her 30th birthday. Her work had a lasting impact on Irish botany, and she was fondly remembered by William Henry Harvey, a fellow botanist influenced by her findings: “[Her] name is held in grateful remembrance by botanists in all parts of the world. To her the botany of Ireland is under many obligations, particularly the cryptogamic branch, in which field until her time little explored. She was particularly fortunate in detecting new and beautiful objects, several of which remain the rarest species to the present day.”

L. Kathleen King (1893 – 1978)

L. Kathleen King, better known as Kathleen, was an Irish botanist and, for a time, Ireland’s leading authority on bryophytes, a branch of botany regarding hornworts, liverworts, and mosses. Born in Dublin, Kathleen attended Loreto College where she demonstrated her aptitude for music, particularly the cello, and theatre. After attending a German finishing school and acting in the Abbey Theatre, Kathleen married Dr Edward Thomas King and they had four sons together, whom they raised in the suburban Mount Merrion area. Edward tragically died, leaving Kathleen a single mother.

Kathleen needed a way to earn money but remain home for her children, so she utilised her garden to supply fruit and vegetables for her family. She found that her garden provided a sanctuary from her grief, and she began to take her botanical interests seriously. She was particularly attracted to bryophytes and bought a microscope to study her specimens further. She published her first scientific paper, Brachythecium caespitosum, with her findings in the Irish Naturalists’ Journal in 1950 when she was 57.

Kathleen expanded her work beyond her home and soon collected specimens from all over Ireland. She joined the British Bryological Society, became the go-to expert for universities, and served as the honorary secretary for the Royal Dublin Society, An Taisce from 1958–64, the president of Dublin Naturalists Field Club from 1955–6 and vice-president from 1957–8, and was part of the Geographical Society of Ireland.

Realising that little work had been done on bryophytes and cryptogams since Ellen Hutchins, Kathleen dedicated the remainder of her life filling these gaps. Her personal herbarium contained over 4000 specimens, which she donated the collection to the National Botanic Gardens, Glasnevin in 1977. She passed away in 1978, aged 84.

Phyllis Clinch (1901 – 1984)

Born in September 1901 in Rathgar, Dublin, Phyllis Clinch was an Irish Botanist who specialised in plant viruses. Phyllis graduated at the top of her class in 1923 from University College Dublin, with a First-Class degree in botany and chemistry. Her high achievement granted her a scholarship that enabled her to undertake a Masters degree, which she obtained in 1924, and she was granted a research fellowship from the Dublin City Council in 1925.

Phyllis then undertook a PhD through London’s Imperial College, exploring plant physiology (how plants function); she looked specifically at the biochemistry of Coniferales (trees including cedar, pine, yew, and juniper) and the metabolism of conifer leaves. During this time Phyllis also published five papers and, immediately after the completion of her PhD, she worked with Alexandre Guilliermond, a specialist in the study of yeast, studying cytology (the function and structure of cells) from 1928 to 1929 in Paris.

Phyllis quickly established her career by becoming a research assistant for the UCD department of plant pathology (the study of disease) and joined a plant virus research group at Albert Agricultural College. Phyllis and her colleagues J. B. Loughnane and Paul A. Murphy published nine papers detailing their research with this group in the scientific journal Scientific Proceedings for the Royal Dublin. Phyllis also published her independent work in Éire, Ireland’s Department of Agriculture journal, and internationally respected scientific journal, Nature. By 1949, Phyllis was a botany lecturer at University College Dublin, and she became the first female professor of the department in 1961. She was also the first woman to receive the Boyle Medal from the RDS (Royal Dublin Society) the same year.

Phyllis’s most important contribution to botany includes science’s understanding of potato viruses. She identified symptomless viruses and viruses that damaged potato stocks, which enabled Ireland’s Department of Agriculture to “develop potatoes free of diseases for farmers which was beneficial to the Irish potato industry”. She also identified viruses in tomatoes and sugar beets.

Phyllis retired in 1971 and moved to Tenerife, Canary Islands, where she passed away peacefully in 1984, aged 83.

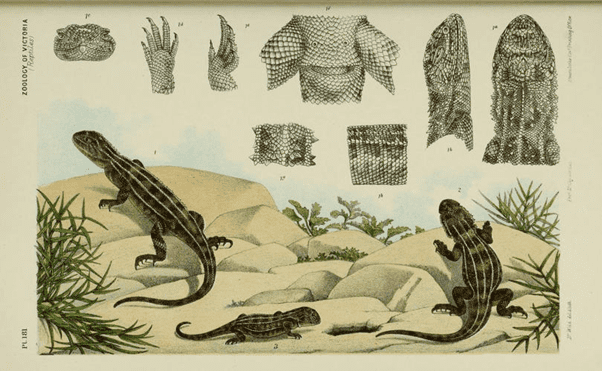

(Source: Museums Victoria Collections)

Female Scientists: Zoologists

The scientific study of the behaviour, structure, physiology, classification, and distribution of animals.

Jane Stephens (1879 – 1959)

Born in Clontarf in Dublin, the same town as Dracula author Bram Stoker, Jane Stephens was an Irish zoologist who pioneered the scientific study of sponges – small sea creatures – in Ireland. Jane was the sixth child of a Quaker couple. She attended Alexandra College, an all-girls boarding and day school in Dublin, where she shone in her academic studies and engaged in tennis and hockey. She went on to study geology and biology at Royal University of Ireland in 1903, becoming the first woman to be granted a degree by this institution.

Jane began her career as a Technical Assistant for the Natural History Division of the National Museum of Ireland in 1905. She later became an Assistant Naturalist. It was here that Jane developed her passion for the study of sponges and cnidaria, an animal classification which includes jellyfish, coral, and sea anemone. She studied the specimens the Natural History Division of the Natural Museum of Ireland had in their collection and published detailed monographs of her findings.

Jane was influential in the Scottish National Antarctic Expedition (1902 – 1904); the expedition returned with numerous unknown specimens of sea creatures and Jane identified 34 of them herself. In 1909, Jane participated in the Clare Island Survey, a zoological, botanical, archaeological, and geological survey of Clare Island an island off the West coast of Ireland; she surveyed the fresh and marine sponges, alongside previously unknown marine invertebrates.

Jane married Robert Francis Scharff, the then acting Director of the National Museum of Ireland and Keeper of the Natural History Division, in 1910. This meant she had to resign her post at the museum, for a marriage bar in Ireland prevented married women from working. After her marriage, Jane did not do any more research or writing, but her work up until that point was a significant contribution to Ireland’s zoological research. Jane passed away in 1959 in London, aged 80.

Carmel Humphries (1909 – 1986)

The first female professor of zoology in Ireland, Carmel Humphries was an Irish zoologist who specialised in the identification and classification of chironomid flies. Born in Waterford, Carmel was educated at the Ursuline convent in Waterford and the at Loreto College in Dublin. In 1929, she enrolled at University College Dublin to study science, where she won a number of scholarships as an undergraduate. She graduated in 1932 with a B.Sc. with honours in botany and zoology. In 1933, Carmel undertook postgraduate studies in zoology and education and was awarded the M.Sc. and H.Dip.Ed, as well as winning the NUI travelling studentship in zoology. Carmel did not wish to teach and, having become interested in limnology (the study of lakes), therefore deciding to travel and study abroad.

Carmel moved to Windermere in England to study limnology under Winifred Frost, T. T. Macan and H. P. Moon at their Freshwater biological station. Her work explored the fauna of Cumbria lake, and the taxonomy of non-biting midges. She published some of her findings in the Journal of Animal Ecology in 1936. Carmel attached herself to August Thienemann, a co-founder of the International Society of Limnology, which enabled her to study the community composition and emergence periods of the Chironomidae of the Großer Plöner See, the largest lake in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany. Her findings were published and Carmel was rewarded a PhD from the National University of Ireland when she returned in 1938.

Carmel worked at numerous academic institutions, including as an assistant in zoology at NUI Galway until 1939, as a senior demonstrator in zoology at University College Dublin from 1939 to 1941 and an assistant at Queen’s University Belfast from 1941 to 1942. In 1942 she was appointed permanently as an assistant in the zoology department at University College Dublin, where she remained for the rest of her career. Carmel was made a statutory lecturer in zoology in 1947 and succeeded James Bayley Butler as head of department in 1957, making her the first female professor of zoology and head of department in Ireland.

Her work made her a leading authority on the taxonomy and ecology of Chironomidae’s in Ireland. She was active in the zoology department of University College Dublin throughout her career and was a member of several bodies, including RIA committee of science, the Royal Dublin Society, and the Institute of Biology of Ireland. She was also a representative for Ireland in the International Society of Limnology and the English Freshwater Association.

Carmel retired in 1979. She is remembered for her tireless work, her photographic memory, and her good humour and generosity. She passed away in 1986, from diabetes-related complications, aged 75.

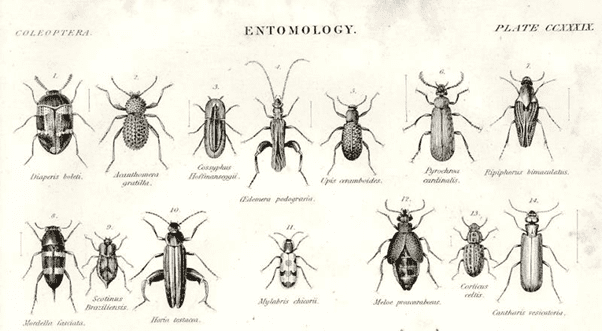

(Source: Zibbet Marketplace)

Female Scientists: Entomologists

Entomology is the scientific study of insects and their relationship to humans, the environment, and other organisms.

Mary Ball (1812 – 1898)

Mary Ball was an Irish naturalist (an area of scientific investigation involving organisms, including animals, fungi, and plants, in their natural environment) and entomologist known for her discovery of the stridulation in aquatic bugs (sound produced by the rubbing together of limbs) and her intensive studies of odonatan, flying insects including dragonflies.

Born in County Cork in 1812, Mary grew up in a well-off Protestant family who were involved in trading. Mary and her siblings were fascinated by science, and it is noted that Mary’s brother Robert began collecting insect specimens with their father at an early age. It is presumed that Mary took part in these collections, for her brother encouraged her interest by buying her a copy of Systematic Catalogue of British Insects by James Stephens. It was within the pages of this volume that Mary catalogued her own findings.

By 1833, Mary had begun communicating with Belfast naturalist William Thompson, who was renowned for his founding studies of the natural history of Ireland, especially in ornithology and marine biology. Thompson oversaw Mary’s ever-growing collection of insects, shells, and molluscs; one of her most interesting finds was a specimen of the migratory locust. Her collection became famous throughout Ireland and a go-to place for entomologists, including Michel Edmond de Selys-Longchamps, the founder of odonatology.

After the deaths of her father and brother, Mary decided not to further pursue science and instead turned to fern gardening. She died in 1989, aged 86. Her enormous collection is now housed in Dublin at the Zoology Museum in Trinity College and the Natural History Museum.

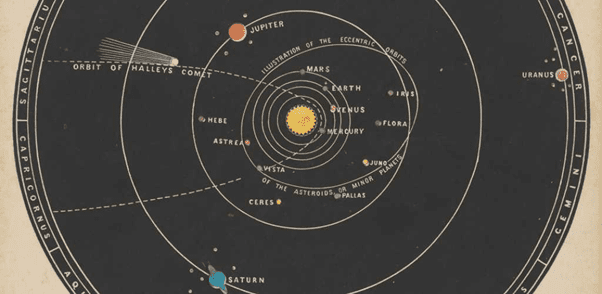

(Source: Royal Museums Greenwich)

Female Scientists: Astronomers

Astronomy is a natural science that studies celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and evolution.

Agnes Mary Clerke (1842 – 1907)

Born in County Cork in 1842, Agnes was an Irish astronomer and writer. Her mother Catherine had been educated at the Ursuline Convent, and therefore placed a great deal of importance on the education of young girls. Agnes, along with her older sister Ellen and younger brother Aubrey, were home-schooled and the girls received a more intensive and inclusive education than was generally expected for girls at the time. Agnes was inspired by her father’s own interest in astronomy; by the age of fifteen, Agnes has been regularly using her father’s 4-inch telescope to observe Saturn’s rings and Jupiter’s moons and was compiling a written history of astronomy. When she turned nineteen, Agnes was tutored by her brother at a university level, studying advanced mathematics, physics and astronomy.

Agnes moved around a fair bit, mostly due to her sister’s health; she lived in Dublin, Queenstown, and Florence, where she studied science and languages, before settling in London in 1877. Upon arrival, Agnes published articles she had written in Italy, Brigandage in Sicily and Copernicus in Italy, in the Edinburgh Review, the first of fifty-five articles she would produce for them.

The publishers of the Edinburgh Review, Adam and Charles Black were working on the ninth edition of Encyclopædia Britannica and, having faith in both Agnes’s intelligence and writing ability, to write biographies of a number of famous scientists, including Galileo, to be featured in the book. Her work was well received and as a result, Agnes was commissioned many times by the Blacks over the years.

Agnes is mostly known now for her work A Popular History of Astronomy during the Nineteenth Century, an accessible piece of writing designed to appeal to the general public. William Fox described it as “remarkable in a literary as well as in a scientific way. She compiled facts with untiring diligence, sifted them carefully, discussed them with judgment, and suggested problems and lines of future research. All this is expressed in polished, eloquent, and beautiful language.” She was gifted at “collating, interpreting and summarising the results of astronomical research.”

In 1888, Agnes spent three months at the Cape Observatory in South Africa, familiarising herself with astronomical spectroscopy, the study of astronomy using the techniques of spectroscopy to measure the spectrum of electromagnetic radiation, including visible light and radio, which radiates from stars and other celestial objects. She was a member of and regularly attended meetings of the British Astronomical Association and the Royal Astronomical Society, and was awarded the Actonian Prize, “septennial award for the “person who in the judgement of the committee of managers for the time being of the Institution, should have been the author of the best essay illustrative of the wisdom and beneficence of the Almighty, in such department of science as the committee of managers should, in their discretion, have selected”, in 1893. Agnes passed away at aged 64 in 1907.

Annie Maunder (1868 – 1947)

Annie Scott Dill Maunder was an Irish-British astronomer and mathematician born in Strabane, County Tyrone. Her father was a minister in Strabane’s Presbyterian Church and her mother was the daughter of a reverend. As a result, Annie and her siblings grew up in a serious-minded household and their natural inclination for academics was encouraged by their parents.

Annie was educated at home before attending Ladies Collegiate School in Belfast (now Victoria College) with her sister Hester. In 1886, Annie won a prize for an intermediate school examination at the age of 18. This enabled her to sit the Girton College (Cambridge) open entrance scholarship examination and was awarded a three-year scholarship of £35 annually. She graduated in 1889 with the equivalent of a second-class degree and at the top of her class in mathematics. She was unable to obtain her BA degree which she would have otherwise earned were it not for the north of Ireland’s insistence that women shouldn’t be granted degrees. Regardless of her lack of official qualifications, Annie was a more than capable intellectual.

Annie briefly worked as a mathematics teacher before applying, twice, for a position at Royal Observatory Greenwich. She was assigned to the solar department and worked as a computer, someone who performs mathematical calculations. She worked on a project to photograph the sun and document sunspots created by the solar maximum, oversaw by astronomer Walter Maunder, who would become Annie’s husband.

Although Annie had to resign from her job upon her marriage, she and Walter collaborated on astronomical work until they retired, particularly as a photographer and computer for solar eclipse expeditions and observation and documentation of the Milky Way. Annie and Walter also developed the butterfly diagram, “one of the most powerful representations of the inner workings of the Sun”, in 1904, and wrote numerous articles and books together. In 1916, Annie was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society (RAS).

Annie passed away aged 79, in 1947.

(Source: EdSurge)

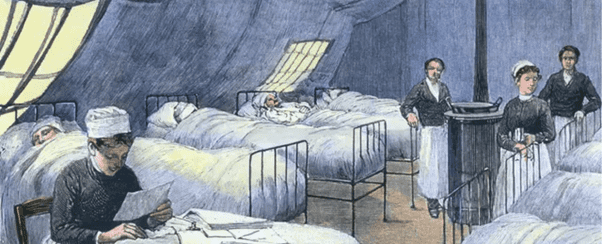

Female Scientists: Medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of establishing the diagnosis, prognosis, treatment, and prevention of disease.

Edith Anne Stoney (1869 – 1938)

Edith Anne Stoney was an Irish medical physicist, the first woman in the field, born into a Dublin-based scientific family. A medical physicist studies “the application of physics concepts, theories, and methods to medicine or healthcare”, and commonly focused on one of two subgroups, radiology or radiation therapy. Edith’s father was a prominent physicist in Ireland – he is notable for his coining of the term electron in 1891 – so her aptitude for science was greatly encouraged throughout her childhood

Edith’s mathematical talents earned her a scholarship to Newnham College, Cambridge, “where she achieved a First in the Part I Tripos examination in 1893”. She was not, however, granted her BA and MA from Trinity, Dublin until 1904, after women were deemed acceptable to grant degrees to. After university, Edith briefly worked for the Irish engineer Sir Charles Algernon Parsons, exploring gas turbine calculations and searchlight design, before taking a teaching post at Cheltenham Ladies’ College, England to teach mathematics.

Edith’s medical career began in 1899 when she was appointed as a physics lecturer at the Royal Free Hospital – she was able to do this after the Medical Act of 1876, which made it illegal for academic institutions to discriminate against hiring female employees. Edith was incredibly passionate about her teaching role, and her course included teaching mechanics, magnetism, electricity, optics, sound, heat, and energy. An ex-student described her lectures: “Her lectures on physics mostly developed into informal talks, during which Miss Stoney, usually in a blue pinafore, scratched on a blackboard with coloured chalks, turning anxiously at intervals to ask ‘Have you taken my point?’. She was perhaps too good a mathematician … to understand the difficulties of the average medical student, but experience had taught her how distressing these could be”.

Alongside her sister Florence, who also worked at the Royal Free Hospital, Edith opened an x-ray service in the hospital’s electric department. The siblings actively supported the women’s suffragette movement and Edith was active for many years in the British Federation of University Women.

During the First World War, Edith offered to provide radiological treatments (a discipline that uses medical imaging to diagnose and treat diseases) for the troops but was denied because she was female. Determined to help, Edith sent supplies from London to Europe to Florence who had set up a unit within the Women’s Imperial Service League, and contacted “the Scottish Women’s Hospitals (SWH), an organisation formed in 1914 to give medical support in the field of battle and financed by the women’s suffrage movement”. They enabled Edith to set up a tented hospital in France, where she could “use stereoscopy to localise bullets and shrapnel and introduced the use of x-rays in the diagnosis of gas gangrene, interstitial gas being a mandate for immediate amputation to give any chance of survival”. Edith moved around Europe for the remainder of the war, doing what she could for the war effort. Her bravery was noted and she was “awarded the “Médaille des épidémies du ministère de la Guerre” and the Croix de Guerre from France, the Order of St Sava from Serbia, and the Victory and British War Medals from Britain”.

Upon her return to England, Edith taught physics as King’s College for Women until she retired in 1925. Her retirement was not empty, however. Edith returned to the British Federation of University Women, became one of the first members of the Women’s Engineering Society, and established the Johnstone and Florence Stoney Studentship in the BFUW, for “research in biological, geological, meteorological or radiological science undertaken preferably in Australia, New Zealand or South Africa” in 1936.

Edith passed away in 1938, aged 69.