Irish Female Artists You Should Know

Updated On: November 07, 2023 by Ciaran Connolly

Ireland has a rich creative history. From literature to theatre, from music to art, Ireland’s innovative and imaginative output has had a major impact on the world. Art, in particular, is one of the Emerald Isle’s strengths. Neolithic Ireland produced stone carvings, Bronze Age Ireland oversaw the introduction of intricate metalwork, and Roman-subjugated Ireland sparked some of the most recognisable motifs of Irish art: Celtic crosses, knotwork, and spiral designs. By the fifth century, Ireland had been Christianised, and its art became characterised by Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, which was predominantly preoccupied with stone crosses and illuminated manuscripts.

Far from the direct influence of the Italian Renaissance, art in Ireland remained relatively unchanged until the 18th century. The mid-1700s saw the development of fine art in Ireland, and several institutions were established to encourage up-and-coming artists, including the Royal Dublin Society (1731) and the Royal Irish Academy (1785). Although many artists travelled to England during the Victorian Era, for it was easier to make a profit as an artist there, the Celtic Revival in 19th and 20th centuries inspired artists not only to remain in Ireland but to use its culture, history and natural landscape as their muse.

It was more common during the late 19th century and early 20th centuries for men to become successful artists as women were expected to be homemakers. A distinct few, however, defied the odds and produced some of Ireland’s most beautiful and imaginative works of art.

(Source: The Times)

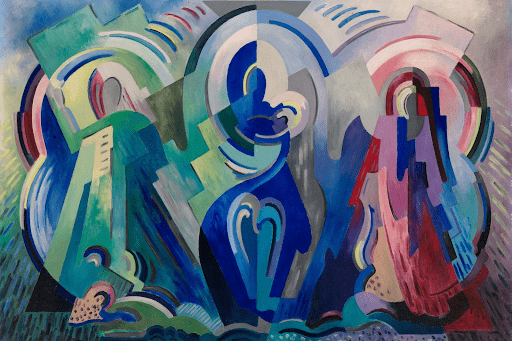

Mainie Jellett (1897 – 1944)

Born Mary Harriet Jellett, ‘Mainie’, as she was better known, was a Modern artist who specialised in the nude female form and the abstract (the Tate Modern explain that “abstract art is art that does not attempt to represent an accurate depiction of a visual reality but instead use shapes, colours, forms and gestural marks to achieve its effect”).

The daughter of William Morgan Jellett, a barrister and later MP, and Janet McKenzie Stokes, Mainie grew up in Dublin. She was introduced to art in an educational sense at the age of eleven, when she was taught to paint by Elizabeth Yeats (a pioneering educator and publisher who refused to remain in the shadow of her famous brothers William Butler and Jack Yeats), Sarah Celia Harrison, and Mary Manning, a highly influential landscape painter.

Mainie went on to study art at Dublin’s Metropolitan School of Art and, unsure of where her creative future lay, also took piano lessons to open up the option of becoming a concert pianist. Whilst at art school Mainie was taught by William Orpen, a commercially successful artist whose main body of work included depictions of war (he was sent by the British government to the Western Front as an official war artist) and portraits of the higher classes of Edwardian society.

Mainie’s decision to become a painter was finalised in 1917 when she enrolled at the Westminster Technical Institute in London. Under the supervision of Walter Richard Sickert, a key figure in Britain’s post-impressionist and avant-garde circles, Mainie showed great promise in her uniquely impressionist approach to art. In 1920, she won the Taylor Art Scholarship worth £50 (£2,249.49 in today’s money) and submitted work to the annual exhibition of the Royal Hibernian Academy.

Her move to Paris in 1921 and her introduction to cubism – an avant-garde art movement, pioneered by Pablo Picasso, characterised by emphasis on the flat, 2-dimensional surface of a picture – helped Mainie refine her signature style. Her work began to focus on colourful and rhythmic non-traditional representation, particularly of women and horses. In Irish Art: A Concise History Bruce Arnold writes that: “Many of her abstracts are built up from a central ‘eye’ or ‘heart’ in arcs of colour, help up and together by the rhythm of line and shape, and given depth and intensity – a sense of abstract perspective – by the basic understanding of light and colour”.

In “An Approach To Painting”, published in 1942, Mainie expressed her deep-seated belief that artists are necessary in society:

“The idea of an artist being a special person, an exotic flower set apart from other people is one of the errors resulting from the industrial revolution, and the fact of artists being pushed out of their lawful position in the life and society of the present day. … Their present enforced isolation from the majority is a very serious situation and I believe it is one of the many causes which has resulted in the present chaos we live in. The art of a nation is one of the ultimate facts by which its spiritual health is judged and appraised by posterity.”

Mainie remained active up in the art world until her death in 1944 from pancreatic cancer. Among the first painters to promote and explore the abstract in Ireland, Mainie is a key figure in Irish art history.

(Source: Irish Times)

Mary Swanzy (1882 – 1978)

Mary Swanzy grew up in Dublin with her two sisters. Her parents, who Julian Campbell describes in his study of Mary in 1986, were part of “the professional Protestant classes who were so influential in that generation”. Her father Henry Rosborough Swanzy was a successful ophthalmic (eye) surgeon who played a key role in forming the Royal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital. Although strict, in keeping with the Victorian ideals of the time, Mary remembered her childhood as “a gift from Heaven”.

Mary later attended Alexandra College, Earlsfort Terrace, a finishing school at the Lycée in Versailles, France, and a day school in Freiburg, Germany. This enabled her to become fluent in both French and German and develop an understanding and appreciation of their approach to art. Upon her return to Ireland, Mary, like Mainie Jellett, Mary gained knowledge and artistic skills through her time at Mary Manning’s art studio, where she developed her talent under the guidance and supervision of J. B. Yeats.

After enthusiastic encouragement from Manning, Mary studied modelling with the Irish sculptor John Hughes at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art. In 1905 Mary presented her work at her first exhibition at the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA), Portrait of a child. She continued with portrait painting until 1910, but ultimately decided it was not the artistic path she wishes to take. She knew her father hoped she would be a portrait painter for they were held in high regard in Victorian and Edwardian society. According to Imma, Mary’s unhappiness with the idea sprung from “the fact that men tended to want to be painted by men. While some of her portraits impart a sense that she is not fully engaged, nonetheless they do show real flair and genuine connection with the sitter, more than enough to indicate it might have been a worthwhile course to pursue. In any case, a consistent exhibitor, she was becoming increasingly well established and respected, in Ireland and eventually in Paris”.

Mary returned to Paris briefly, where she attended the studio of Antonio de La Gándara, a famous painter, pastellist and draughtsman, in 1906, and took classes at Académie de la Grande Chaumière and Académie Colarossi. Her time in Paris introduced her to the works of Gauguin, Matisse, and Picasso (whom she met personally at one of Gertrud Stein’s infamous soirées). Their work made a lasting impression on her.

Mary continued to have much success with her art, which she often displayed at exhibitions, before the deaths of her parents. Although their passing left her financially independent, the devastation of their loss had a major impact on her. Heartbroken, she eased her sorrows with travel and the continuous outpouring of artistic pieces. Although her later career would be characterised by more abstract art such as cubism and fauvism, an impressionist path dominated by non-tradition representations via bold colours, Mary spent the late 1910s depicting landscapes, village lives, and peasant scenes, mostly using crayon. These were inspired by her life in Ireland and what she saw on her travels with her sister, who was involved with the Protestant relief mission in Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia.

Drawn to more exotic spaces, Mary spent most of the 1920s travelling to the likes of Honolulu, where she stayed with an uncle. On a letter to her friend and contemporary artist Sarah Purser, she wrote of the “perfect climate and beauty … I feel a draw towards tropical scenes”. Most of her major works were completed during the 1920s.

When she settled in London, Mary began experimenting with abstract art, particularly Orphism, an offshoot of Cubism which focused on sheer abstraction and bright colours. Her non-traditional work became largely allegorical.

Mary continued creating and exhibiting her art until her death in 1978.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Sarah Purser (1848 – 1943)

Born in Dún Laoghaire (formerly Kingstown) in County Dublin, and raised in Dungarvan, County Waterford, Sarah was the youngest of eight children. Her father Benjamin was a successful flour miller and brewer. When Sarah turned thirteen, she moved to Switzerland to be educated at the Moravian school, Institution Evangélique de Montmirail, where she learned to paint and speak fluent French.

Her father’s business took a bad turn and began to fail in 1872, before collapsing completely in 1873. Benjamin and his wife, Anne, split up. Benjamin emigrated to America and Anne moved the family to Ballsbridge. This financial decline led Sarah to pursue painting as a full-time career.

To learn all she could, Sarah enrolled at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art and joined the Dublin Sketching Club, before moving to Paris to study at the Académie Julian, a private art school for painting and sculpting. It was here she met fellow artists with whom she maintained lifelong friendships, including German-Swiss painter Louise Catherine Breslau, Ukrainian-French sculptor Marie Bashkirtseff, and French impressionist painter Berthe Morisot. According to the Jorgensen Museum of Fine Art, one of Sarah’s most famous paintings, Le Petit Dejeuner, dates from this period: “in this painting she depicts her friend, Maria Feller, who was studying music in Paris, at that time, seated at a breakfast table in a Parisian cafe, lost in thought. Portrait painting was to become Sarah Purser’s forte throughout her long career as an artist”.

Sarah returned to Ireland in 1880 and exhibited her art throughout the most prestigious art galleries in the country. She was an intelligent woman who endowed her financial earnings wisely, and became incredibly wealthy thanks to these investments, particularly her investments in Guinness. This financial stability enabled her to paint as and when she pleased, and as she was active in high social circles, particularly in Dublin’s art scene, she often had a variety of portrait commission to choose from.

Sarah thought it important to invest in her local community. She was actively involved in the establishment of the Hugh Lane Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, the acquisition of Charlemont House to house the gallery, and in “1903, she established “An Tur Gloine” (The Glass Tower) in order to develop and sustain an indigenous Irish stained glass industry. Many important stained-glass windows in churches throughout Ireland were produced there and most of the major Irish stained-glass artists, such as Evie Hone worked there, until its closure in 1944.” Although she mostly painted portraits and took on a more supervisory and directorial role at An Tur Gloine, Sarah did invest some time in creating her own stained-glass windows: St. Ita for St. Brendan’s Cathedral, Loughrea and The Good Shepard for St. Columba’s College, Dublin are believed to be her works.

Sarah is a key figure in Irish art history not just for her own artistic contributions and establishment of artistic institutions, but for showing other women of the era that art was a viable option for women. Sarah died in 1943 and is buried with two of her brothers at Mount Jerome Cemetery in Dublin.

(Source: Whyte’s)

Mildred Anne Butler (1858 – 1941)

Born into a privileged family, Mildred Anne Butler grew up in Kilmurry in Co. Kilkenny. She was the youngest daughter of Captain Henry Butler, a grandson of the Edmund Butler, 11th Viscount Mountgarret; an amateur artist himself who was fascinated by the unique plants and animals he encountered abroad, it is likely his love of art motivated his daughter. This, as well the idyllic rural area she grew up in, would serve as inspiration for Mildred’s later artistic career.

Mildred began learning about art in a serious manner in the 1880s through her training with the watercolourist Paul Jacob Naftel in London. Rather than follow in his footsteps and use watercolours strictly for vast landscapes, Mildred used rural animals such as cattle and donkeys, gardens, and birds as her subjects. Her love of painting animals was encouraged by William Frank Calderon when she enrolled at Westminster School of Art. Calderon specialised in animal painting and later opened a school specially dedicated to the subject. Whilst at Westminster, Mildred became particularly talented in her depiction of cattle, and it was this talent that earned her a place at the Royal Academy of Arts.

Upon the completion of her studies, Mildred travelled extensively around France (where she studied drawing, figure drawing, and fine art painting), Belgium, Switzerland and Italy. During these trips Mildred established and maintained a relationship with the Newlyn School in Cornwall. This school was made up of a small group of artists in a fishing village, and their emphasis was on painting outdoors and using natural light as a source of inspiration for their outdoor settings. This connection enabled Mildred to befriend fellow artists including wartime painter Sir John Lavery, impressionist landscape painter Walter Osborne, and Stanhope Forbes, the founder of the Newlyn School.

Mildred had an exponentially successful career in realist watercolour art. She was a favourite of famous figures including Louis IV, Grand Duke of Hesse and Queen Mary of Teck, “a member of the Society of Lady Artists, the first nine academicians elected by the Ulster Academy of Arts in 1930, and she was granted full membership into the Royal Watercolour Society in 1937, having been an associate member since 1896”.

Mildred developed arthritis in the late 1930s and was forced to stop painting as it caused her considerable pain. She died, aged 83, in 1941.

(Source: Whyte’s)

Letitia Marion Hamilton (1878 – 1964)

Letitia Marion Hamilton, known as May to her friends, was born in Hamwood House, County Meath in 1878. Her great-grandmother was the artist Marianne-Caroline Hamilton, who specialised in pencil drawings, and her cousin was the distinguished watercolour painter Rose Maynard Barton.

Letitia was ‘horse Protestant’, according to Hilary Pyle, meaning that she had a fortunate start in life. She was sent to Alexandra College with her sister Eva, a prestigious independent boarding and day school for girls, by her parents Charles and Louisa. Letitia and Eva both showed a naturally aptitude for art, so they enrolled at the Dublin Metropolitan Art School under the supervision of William Orpen.

Letitia studied a variety of art styles, but she was particularly drawn to art nouveau (an intricately decorated art style characterised by its use of asymmetrical lines), modernism and enamelling; she was so good at this that she was awarded a silver medal in 1912 by both the School and the Board of Education National Commission. Letitia continued her art studies at the Slade School of Fine Art in London and in Belgium with Frank Brangwyn, a self-taught eccentric artist who dabbled in various arts including painting, drawing, sculpting, glassware, and woodcutting.

The Irish countryside would prove to be Letitia’s strongest muse. Her first exhibition in 1902, at the Royal Hibernian Society, featured over 200 paintings, most of which were landscapes or small-scale studies of rural life. She travelled extensively and was particularly fascinated by France, where she was exposed to Impressionism for the first time, and Italy, where she refined her style by painting while riding gondolas; she used these paintings to explore light effects, pastel shades, and strong outlines, and later incorporated these new skills into her Irish landscapes. These works are considered among her best.

Letitia exhibited her work in many galleries Ireland, but her exhibits are not her only claim to fame: in 1948 she became the last person to win a bronze medal at the art competitions at the London Olympic Games, forever cementing her place in art history.

The older she got, the more Letitia’s eyesight failed her and although she painted for as long as she could, she eventually passed away in 1964, aged 86.

(Source: Adam’s)

Helen Mabel Trevor (1831 – 1900)

Born in Lisnagead House, Loughbrickland, County Down, Helen Mabel Trevor was the eldest daughter of Edward Hill Trevor, Esq. Mabel enjoyed drawing and painting from an early age and was constantly encouraged by her friends and family; by the time she was 8, her nursery’s walls were covered from floor to ceiling with her creative works. Her father eventually provided her with her own studio where she could practice. She particularly enjoyed doing sketches of dogs.

Mabel did not have a formal art education in her youth, so she was largely self-taught. In 1853, she decided to send her two works, The Youthful Mechanic and Portrait of William III, to the Dublin Exhibition, and submitted her Sketch from Life to the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA) the following year. She submitted more works depicting cats and dogs to the RHA in 1856, along with a portrait.

It was not until the death of her parents in the 1870s that she finally began her formal art education. Aged 45, Mabel attended the Royal Academy schools in London from 1877 to 1882 and later travelled to Paris where she studied with French chiaroscuro painter Jean-Jacques Henner, French painter Carolus-Duran, and Luc-Olivier Merson, a French academic painter and illustrator who became known for his currency and postage stamp designs. Mabel also travelled to Brittany and Normandy with her sister Rose.

The 1880s proved to be a productive time for Mabel, with some of her most famous paintings being sent to various galleries for exhibition, including Breton boys en retenue and Two Breton girls. Mabel and Rose moved to Italy to study, and it was here that Mabel began to incorporate more realism into her work, key examples being A Breton widow, The Hills of Perugia and Venetian bead stringers, all of which were exhibited by the RHA.

Mabel returned to Paris in 1889 and settled there permanently, often travelling to Brittany and moving to different addresses in Paris. Her later works were well received and often exhibited at the Paris Salon and around Irish galleries.

In 1900, Mabel died suddenly and unexpectedly of a heart attack in her studio at 33 rue de Cherche-Midi, Paris.

(Source: Ross’s Auctioneers)

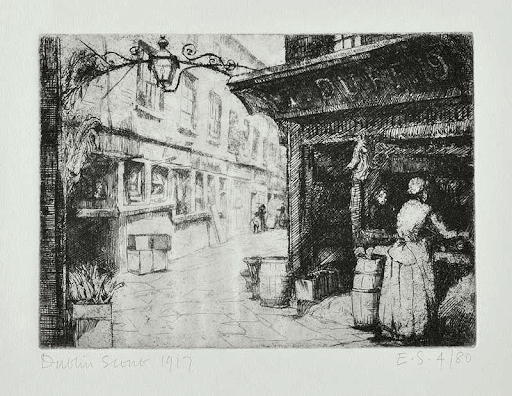

Estella Solomons (1882 – 1968)

Estella Francis Solomons was born in Dublin, Ireland in 1882 to Jewish optician Maurice Solomons and poet Rosa Jane Jacobs. Her father and brother are famously mentioned in James Joyce’s Ulysses.

At the young age of 16, Estella won a prize that enabled her to enrol at the Dublin Metropolitan School of Art where she studied, like many of her contemporaries, under William Orpen. She also attended the Chelsea School of Art from 1903 – 1906, studied drawing from Life and the Antique at the Royal Hibernian Academy under Walter Osborne, and, studied at the Académie Colarossi studio in Paris. It is also likely that her main point of artistic expression, printmaking, was inspired by her trip to the tercentenary exhibition of the work of Rembrandt in Amsterdam in 1903.

Estella’s signature works were etchings, watercolours and oil-painting portraits, which were characterised by their unsentimental, academic approach. She also illustrated books for Padraic Colum and DL Kelleher.

Upon her return to Ireland, Estella exhibited her work in the Leinster Hall, Molesworth St., alongside contemporaries such as painter, sculptor and stained-glass artist Beatrice Elvery and cartoonist Grace Gifford, who famously married her fiancé Joseph Plunkett in Kilmainham Gaol only a few hours before he was executed for his part in the 1916 Easter Rising. Estella’s work was also included in exhibitions with other artists at Mills Hall in 1919 and the Arlington Gallery, London in 1935. She also exhibited at her Great Brunswick St. studio in 1926.

Aside from her artistic work, Estella was heavily involved with Irish politics. She was of republican persuasion, a member of Ranelagh branch of Cumann na mBan, and often used her studio as a safe house for Republican voters. Estella married James Sullivan Snarkey, better known as Seamus O’Sullivan, after the death of her parents who disapproved of the marriage as O’Sullivan was not Jewish. The couple collaborated on renowned literary and art magazine Th Dublin Magazine, of which O’Sullivan was the editor for 35 years.

Estella continued to paint and etch, and in her later years became an art teacher. She died in 1968.