The Curious Case of Irish Curses and the Magical Cursing Stone

Updated On: November 10, 2023 by ConnollyCove

The island of Ireland has always had its own unique culture. The Emerald Isle is a melting pot of the ideas of the various groups that lived here over many millennia, but our history does share some similarities with the rest of the world.

Curses, for example, are a common part of many different mythologies, and the mythology of Ireland is no different. We do, however, have our own unique interpretation of curses. Irish curses have a fascinating history that isn’t known by many people, and there is a reason for that.

Irish curses appear in mythology, but not how you would expect. Irish curses don’t always thwart a hero’s mission; sometimes, they do the opposite. There are even some preserved pagan cursing stones found at Christian holy sites, which, from an outside perspective at least, doesn’t make sense!

In this article, we will explore the oddities of Irish curses and more. So, let’s dive into the haunting and mysterious history of Irish curses and cursing stones. Scroll down to read through the article, or click on one of the highlighted sections below to jump ahead!

Table of Contents

The Origins of Irish Curses

Curses in Ireland come from the usual roots of mythology and include folk magic and charms. Curses, although not always, were usually used for nefarious means. The good versus evil model is simple and was always popular in Irish folk tales.

There are many famous examples of spells and curses in folklore. One popular legend states that there was a spell placed on Etain that turned her into various animals. Another folk tale tells of King Suibhne, who was cursed by St. Ronan and became a half-bird, half-man creature. There was also the curse placed on the children in the story of the Children of Lir that turned them into swans for 900 years.

In folklore, these acts of magic qualify as curses because they are malicious, inflict hardship on the victim, and are contingent on a set of extreme circumstances before they can be lifted or, in some cases, are irreversible.

In the myths, every country and every town had its own peculiar curses. Curses can be brought upon someone accidentally by falling over a rath or fairy fort or deliberately by attracting a curse from an enemy.

Cursing a person involves wishing bad luck or evil on them or someone they love by invoking a non-human power, and is found in many different cultures around the world. In most cases, a curse involves using a formula (e.g. a prayer or spell – whatever you want to call it!) and an associated prop, ingredient, or personal object associated with the person you want to curse.

Thus far, Ireland is like any other country when it comes to the mythos surrounding curses. However, their Filiocht (poets) bequeathed to them another rich magical strain—one which contained rules that allowed for just cursing and punished unjust curses.

Irish Cursing Stones

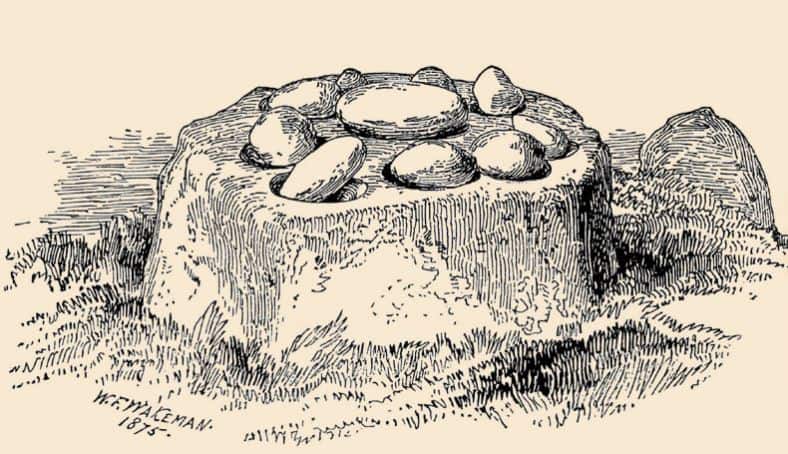

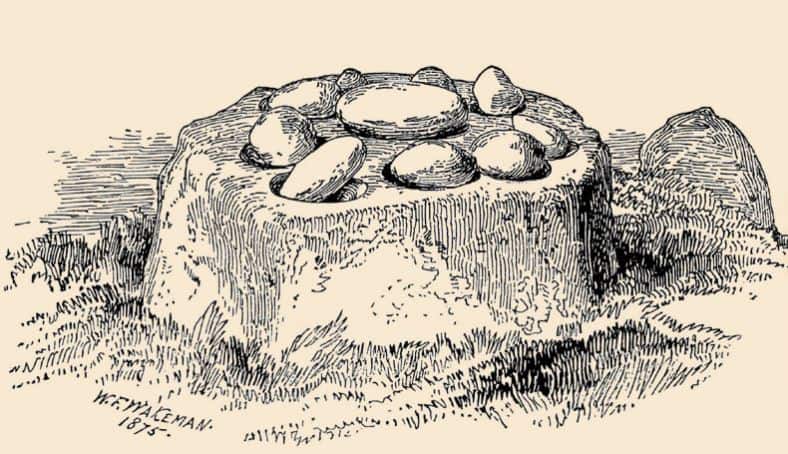

Cursing stones were part of a ‘bullaun‘, which is believed to mean bowl. It was a stone that had a depression (a shape carved into the stone to create an indent, like a bowl) in its centre, which held water. The bullaun had the power to curse someone, but only if the punishment was just. If not, the person who performed the ritual would receive the curse.

Natural rounded pebbles or boulders were sometimes found in the bullaun, and these were known as cursing stones. Apart from the similarities we mentioned, each surviving bullaun is relatively unique. Their size, shape and other features change quite drastically.

Interestingly, the bullaun was not just associated with detrimental effects; it was believed that rainwater collected in the bullaun had healing properties. Even more interesting, the stone could also be used for a blessing.

Blessings and curses were seen as opposites of each other, so the process of cursing often involved moving the stone in the opposite direction of a blessing.

The position of cursing stones in Irish folklore is poorly documented, perhaps due to their malevolent nature but also due to the fact that the Celts did not record their history in Ireland. Their history has been pieced together by using records from other nations and countries at the time who mentioned them, as well as the artefacts and archaeological sites that they left behind.

It was only when Christian monks began recording the history of Ireland that much of the Celtic way of life, such as mythology, was transcribed. The monks attempted to merge the Celtic faith with Christian values.

By then, Celtic life had been merged with Christian ideals, which drastically changed their way of life, folklore, and culture. Not everything the Celts did fit into Christian values, and so some things have very little information surrounding their existence, as they were intentionally left out of the monks’ records.

While the early Celtic Christian church absorbed many of the Pagan beliefs of old Ireland, the idea of adapting Irish curses into the Christian ideology was naturally unfavoured. Sacred wells became holy wells easily enough, just as the myths of Pagan heroes became the miracles of saints. This explains the story of Brigit, the Goddess of the Tuatha de Danann and her resemblance to Saint Brigid.

There are many similarities shared alongside the name of the two deities, including the fact that Saint Brigid’s Day is celebrated on the same day as Imbolc, one of the four ancient Celtic festivals. Brigit was the Goddess of Fire, Light, Fertility, the Hearth, the Forge and Creativity.

Because she represented dominant positive things, it was very hard to get the ancient Irish people to stop worshipping her. So, they turned her into a saint.

However, the polar opposite of the sacred wells were the bullauns, which contained cursing stones. These were not so palatable to the Christian faith. The notion of uttering curses to damn one’s enemies was in stark contrast to the views of Christianity.

So, the stones were never part of the canon of the Celtic church once the faiths were merged. The Celtic church was the amalgamation of Celtic pagan customs into the Christian faith during medieval Ireland. It returned to the standard Catholic Christian format during the Norman ascendancy over the island.

It was easy to fix this issue; once the stones were removed, the bullaun was harmless and could only serve as a water basin.

It makes sense that instead of trying to change the dominant religion in the country entirely, early Christian missionaries would try to merge suitable existing traditions with their mission. They would only leave out the things that were unacceptable in their faith. Curses definitely fit this criteria, so it does make sense.

What We Know About the Cursing Stones

It is believed that only two cursing stones have survived throughout history and still exist today. The rest have been lost or destroyed, presumably by the Catholic Church. However, there is also evidence that many more exist.

These are lesser known but fit the criteria of a bullaun, so it is hard to decide on one number. Such are the joys of the ambiguous nature of Irish mythology! Whatever the actual number is, the unfortunate truth is that the majority of ancient Irish cursing stones were destroyed.

The remaining stones are often found at holy sites. It is not unusual for an old stone church to have a carved basin in its wall to hold holy water, which the clergy use to bless themselves as they enter the church.

Most of what we know about cursing in terms of cursing stones comes from folklore, as well as the remnants of ritual traditions. But when you take a step back and look at everything in context, you can see that, in most cases, the curse seems to be about a reverse of positive powers.

This reverse motif occurs everywhere. A spell, for example, is often considered the opposite or the reverse of a prayer. So, once the stones were removed, the former bullaun was only associated with positive blessings.

It is also believed that there were rituals involved in the use of bullauns, including fasting before making a curse and leaving offerings. A commonly portrayed ritual used when performing a curse is taking repetitive actions, such as turning the stone anti-clockwise, while the curse is cast.

What the Cursing Stones Meant in Ireland

In Ireland, cursing stones are generally associated with early ecclesiastical sites and involve the invoking of power by an early Christian saint. As part of the early Christian tradition, pilgrims would often go to these sites and recite a prayer while turning the stone clockwise. Or, if they wanted to curse someone, they would turn the stone anti-clockwise (against the sun and other natural processes).

It is more than likely that this process involved worshipping Celtic Gods and Goddesses long before Christianity arrived in Ireland. It would have taken a long time to break any tradition completely, and we already know that many Celtic traditions were adjusted but preserved.

The cursing stones themselves were simple enough, and indeed, several survive to this day. One or more round stones would rest in the depressions on larger stones. They are of Neolithic origin and are considered to be a subset of the “cup-marked boulders” found across Europe.

Sometimes known as bullauns (from the bowl-like depressions in which the stones rested), a common Christianisation of the practice was to remove the stones and use the depressions to hold holy water. It was thought that removing the small stones would remove the nefarious magical ability of the larger stones, rendering them harmless.

Some bullauns still retained their stones and their cursing legends, more than likely in more rural areas. However, the majority were used solely as blessing stones from then on or were destroyed entirely.

The Geas in Irish Mythology – Irish Curses

In Irish mythology, the geas was comparable to a curse, prohibition, or taboo. They were sometimes even considered a gift. The geas was usually a spell that prohibited an action to be taken. If the spell was broken, the person it was cast upon would suffer misfortune even if they didn’t know about the geas.

The most interesting thing about the geas is that heroes in Celtic mythology would use them to their advantage, essentially creating a prophecy that would foretell their death in a bizarre and unusual way. The idea of this would be so far-fetched that heroes could fight many battles unscathed, knowing their chances of defeat were nearly impossible.

For example, the Welsh hero Lleu Llaw Gyffes had a geas that stated he would neither die at day or night, on land nor water, nor indoors or outdoors and so on, which made his death nearly impossible.

The Incident on Tory Island – An Irish Curse?

From avoiding black cats and walking under ladders to making the sign of the cross to ward off evil, the Irish have a long history of believing in the power of the supernatural. The people of Tory Island are no exception in the curious case of the sinking of the HMS Wasp ship.

Tory’s history is full of mystical stories ranging from blessed clay that prevented rodents from living on the island to magic water fonts, secret charms, and enchanted stones. But most people believe the tales to be nothing more than folk legends, told as a throwaway comment to easily explain the inexplicable and amuse the masses.

The Sinking of the HMS Wasp

However, one tragic incident is still rumoured to be the result of an authentic Irish curse: The sinking of the HMS Wasp.

The HMS Wasp was a Royal Navy gunboat built in 1880. It was mainly used to transport officials to and from the islands for lighthouse and fishery inspections, as well as other official duties. The boat was used to deliver a supply of seed potatoes donated by the Quakers to help the poor in Donegal and on Tory Island in 1883, so it had a mixed reputation with the people there.

On 22 September 1884, three families on the island could no longer afford rent. Their landlord ordered their evictions to set an example for the other tenants. The HMS Wasp would again set sail for Tory Island, but this time, instead of bringing relief to the islanders, the ship was carrying the bailiffs and police who were to carry out the eviction.

And so it did; the HMS Wasp set sail from Westport, County Mayo, to collect taxes and deliver eviction notices to Inishtrahull Island off Malin Head. It was on course between Tory and the mainland when disaster struck.

At around 3:45 AM, the HMS Wasp hit the rocks directly beneath Tory’s lighthouse. The ship sank to the bottom of the ocean in less than half an hour. Out of all the men onboard during the tragedy, only six survived.

What Caused the Ship to Sink?

It is uncertain exactly what happened on board the HMS Wasp in the early hours of the 22nd of September as it approached Tory Island. The senior officers were asleep, leaving more junior crewmen to man the boat.

This was probably not the wisest choice for the senior officers, given the poor visibility and the difficulty of their route to the island. However, it was a course that the ship had sailed many times before, and those who survived were cleared of any wrongdoing.

It may have been the inexperience of these younger men that saw them plot a different course from the standard route, sailing between the island and the mainland rather than around the outside of the island. Also, unusually, the ship’s boilers were not in use, leaving it devoid of steam power.

This was not a crippling problem, as the ship was perfectly capable of travelling entirely under sail. But, it left the crew with no ability to perform fine manoeuvres in the case of an emergency. When the ship collided with the island’s reefs twice, the junior sailors attempted to get to their lifeboats, but there was simply not enough time.

Surely, it must have been stormy conditions that hindered their journey, right? Well, not really. Actually, the weather was reported as clear and breezy. It was only after the tragic incident, when people tried to reach the island during the following days, that a storm began.

By all accounts, the survivors were well looked after and treated as celebrities after the tragedy. The official court-martial did not blame the sinking on a curse or the crew but did recognise the insufficient experience of the navigating lieutenant.

The story goes that the ancient cursing stones were used to cast a curse upon the HMS Wasp to prevent it from coming to evict the Tory Islanders. A local priest is said to have been disgusted by these Pagan claims of curses, became enraged, and is said to have taken the stones and thrown them over the cliff into the sea.

While the priest removed the stones from the bullaun to ensure any further speculation of supernatural curses in the future would be impossible, this could have easily fuelled the rumours of a curse sinking the HMS Wasp. People who want to believe in the Irish curse could have seen the act of removing the stones as a sort of confirmation that they did have some power.

In truth, this story has become a myth in and of itself. While the ship did sink, the stories relating to before and after the event vary drastically from person to person. Some claimed to see an old woman turning the stones, while others swear the bullaun was not destroyed entirely but is instead hidden somewhere on the island.

Tory Island is certainly no exception to the Irish rule of magic stones. As small as this island is, it boasts two magical stones: the Cloch na Mallacht, the cursing stone mentioned in the story, and the Leac na Leannán, a wishing stone.

The Wishing Stone sits at the top of Balor’s Fort on the island. It is located out on a cliff 100m above the Atlantic Ocean. A wish was allegedly granted to anyone who could throw three stones onto its crest.

The Cursing Stone was located at the west end of the island, but it is now missing. Someone has either taken or destroyed the stone, as we have established.

The Positive Magic of Other Irish Stones

Stones in Ireland have long held a mystique of their own, as we have now discovered. Myths surrounding the supernatural power of Irish rocks are not always related to curses. One reason for Ireland’s strong belief in stone magic could be attributed to the Celts and their religious devotion to rocks and the natural world in general.

Ireland boasts some of the most significant collections of wishing and cursing stones anywhere in the world.

A brief mention of New Grange:

Standing stones, court cairns, portal dolmens, and passage tombs such as New Grange were all created thousands of years ago during the Irish Stone Age, which was long before the Celts arrived in Ireland. The relationship between New Grange and the sun is a fascinating one: the inner tomb of New Grange only lights up during the Winter solstice, illuminating the room inside.

While New Grange is not magic, it is an extraordinary archaeological, engineering, astronomical and mathematical feat. We explore the significance of New Grange and other Stone art/architecture in our article ‘Irish Art History: Amazing Pre-Christian and Celtic Art‘.

The Magic of the Blarney Stone:

The famous Blarney Stone near Cork, Ireland, is a perfect example of a magic stone that has more benevolent roots in mythology.

The origin of the Blarney Stone is linked to Clíodhna, the Celtic Goddess of the Banshees. The banshees were a type of lone fairy in Irish myth associated with impending death. Cormac Laidir MacCarthy, who built Blarney Castle, found himself in a lawsuit. He pleaded with the goddess for help, and Clíodhna told him to kiss the first stone he found on his way to court.

Cormac did this and spoke his case eloquently and actually won. This is just one of many versions of the legend. They all vary greatly but share the same sentiment: the stone provided the person to speak charmingly and almost deceptively without causing any offence.

Other versions include Cormac convincing the Queen of England to let him keep his land and the story that Robert the Bruce gifted the stone to the King. The term ‘blarney‘ means beguiling but misleading talk, and so each case involves using the stone to deceptively get your way and overcome seemingly impossible tasks with your words alone.

The legend says that those who kiss the rock will be granted the gift of the gab. Many visitors to Blarney Castle risk bending over backwards to reach the stone with their lips in the hopes that they receive the Irish blessing.

The gift is something everyone would enjoy, so it is no wonder that politicians, singers and even celebrities have visited the Blarney Stone!

Irish Curses, as Told By the Filiocht

The greatest insight into cursing rituals in Ancient Ireland comes to us through that Druidic class, namely the Fili (poets), who were honoured for their powers of foresight, eloquence, mastery and knowledge of poetic forms and styles.

They were the keepers of knowledge for Kings and understood best the magical power of words. The druids used words to create magic. They also were known to have powerful words in a more metaphorical sense, as their opinions were closely listened to. They could easily make or break a person’s reputation.

The Rise of Piseogs – Unique Irish Curses

As we have covered, Irish curses would only come true if the punishment was just and fair. However, there were also charms and spells called ‘Piseogs‘, which anyone with ill-intent, malicious notions, or even pure jealousy could enact on a neighbour without any reason.

These curses were more akin to modern superstitions, such as gaining bad luck from walking under a ladder or breaking a mirror.

The existence of piseogs was a popular belief in rural areas of Ireland in the past. It made people quite paranoid as luck was seen as something that could be taken away from someone for malevolent reasons rather than a random chance of misfortune.

Efforts to prevent piseogs involved using holy water and blessing each other, in addition to other Christian methods. People also believed that the charm sometimes involved a ritual burying of a simple everyday object used to symbolise something more significant. If a person could dig up the object, it would break the piseog cast upon them.

There were different types of piseogs, ranging from “low” curses (i.e. basic folk magic) or general bad luck to “high” curses, immensely powerful spells arranged for an important specific purpose that could ruin a person’s wealth, livestock or health.

In consequence, there were many anti-curses and charms used to prevent yourself from misfortune. Many Charmers and local practitioners in rural areas are believed to have made a steady income at one point by charging money to remove curses and jinxes.

The likelihood was that if an animal was badly cursed or a human was less severely cursed, the local wise man or woman would be your first port of call. Alternatively, very severe, life-threatening curses would be referred to the local priest.

Of course, some myths claimed that the less-than-life-threatening kinds of curses were often placed by the wise man or woman in the first place.

A list of the actual superstitions or piseogs in Ireland could fill an article themselves, but here are a few you may have heard of as some Irish people still perform countermeasures against Irish curses today:

- An itchy nose signifies that you will get into a fight – A mock fight (mimicking a light punch on a friend) was the only way to prevent a real fight.

- A solo magpie brings sorrow – Waving at the magpie will ward off the bad luck.

- Disturbing a fairy tree will bring bad luck – Many farmers will leave fairy trees in their fields.

- If a visitor entered the home when someone was churning butter, they should churn once to show that they wish good fortune on the family.

- An itchy hand signifies money is coming your way!

Irish Curses are a Fascinating Part of Folklore

Ultimately, the Irish are and will always be renowned for their unrivalled capacity to spin a tale and tell a fascinating story. We have a history full of dark, mysterious legends and tall tales, as well as hopeful and heroic myths that focus on all that is good.

Irish mythology and folklore are full of magic, curses, and conundrums to be explored. Still, Irish curses are also deeply rooted in a past of optimistic opportunities and festivities celebrated by people who wanted to see the light in the dark times.

One of the most interesting things about Irish curses is that they were seen as the opposite of a blessing instead of something completely different. Objects like the bullaun were not inherently bad or evil; it was up to people themselves to decide how to use them.

That being said, the Irish aren’t willing to take any chances when it comes to luck, so you will still see a few people wave at a lone magpie or avoid disturbing a fairy tree to avoid falling victim to Irish curses. The fact that Irish mythos are so ambiguous leaves much room for magic and curses to explain the otherwise unknown gaps in stories.

Have you ever heard any fascinating stories involving Irish curses? We would love to read about them in the comments below!

Other Worthy Reads:

Get to Know Some of the Most Famous Irish Proverbs| Digging into the Secrets of Irish Pookas| Dive into the Finest Legends and Tales of the Irish Mythology| Legendary Castles in Ireland: The Truth Behind the Irish Urban Legends|