Charlotte Riddell: The Queen of Ghost Stories

Updated On: November 07, 2023 by Ciaran Connolly

Christened Charlotte Eliza Lawson Cowan and known as Mrs J. H. Riddell in her later years, Charlotte Riddell (30th September 1832 – 24th September 1906) was a Victorian-era writer born in Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland. Publishing over fifty novels and short stories under various pseudonyms, Charlotte was also part-owner and editor of St. James’s Magazine, a prominent and widely popular London-based literary journal in the 1860s.

Early Life of Charlotte Riddell

Source: Find A Grave

Charlotte Riddell grew up in Carrickfergus, a large and predominantly protestant town on the north of Belfast Lough. Her mother Ellen Kilshaw came from Liverpool, England, and her Carrickfergus-born father James Cowan was the High Sheriff of Antrim; this was a highly sought-after position as the reigning Sovereign’s judicial representative for this area, and it was often accompanied by administrative and ceremonial duties, as well as the execution of High Court Writs.

Charlotte Riddell’s upbringing was a comfortable one. Her family were wealthy enough for her to be educated at home as opposed to a public school, and her natural intelligence and aptitude for creativity was encouraged by her various private teachers and tutors. A gifted writer from a young age, Charlotte Riddell had already completed a novel by the time she was fifteen. Speaking to Helen C. Black, in an interview for the book Notable Women Authors of the Day (1893), Charlotte said: “I never remember the time when I did not compose. Before I was old enough to hold a pen I used to get my mother to write down my childish ideas and a friend remarked to me quite lately that she distinctly remembers my being discouraged in the habit, as it was feared I might be led into telling untruths. In my very early days I read everything I could lay my hands on, The Koran included, when about eight years old. I thought it most interesting.” About the novel she wrote at 15, she said: “It was on a bright moonlight night—I can see it now flooding the gardens—that I began, and I wrote week after week, never ceasing until it was finished.”

Relocation to London: Charlotte Riddell’s Adventure

Charlotte Riddell’s fortune changed when her father died around 1850/1851. She and her mother struggled financially for four years before deciding to relocate to London, where Charlotte hoped to provide for herself and her mother through writing. By this time writing was becoming a more respectable career choice for women, but it should be noted that it still was not as easy for a woman to be published compared to a male writer and a woman’s success, on average, was less than her male counterparts. This understanding likely led Charlotte Riddell to publish her work under gender-neutral pseudonyms during the establishing years of her career.

On leaving Ireland, Charlotte said: “I have often wished we never had so decided, yet in that case, I do not think I ever should have achieved the smallest success, and even before we left, with bitter tears, a place where we had the kindest friends, and knew much happiness, my mother’s death was—though neither of us then knew the fact—a certainty. The illness of which she died had then taken hold of her. She had always a great horror of pain mental and physical; she was keenly sensitive, and mercifully before the agonising period of her complaint arrived, the nerves of sensation were paralysed; first or last, she never lost a night’s sleep the whole of the ten weeks, during which I fought with death for her, and—was beaten. (…) Coming as strangers to a strange land, in all London, we did not know a single creature. During the first fortnight, indeed, I thought I should break my heart. I had never taken kindly to new places, and, remembering the sweet hamlet and the loving friends we had left behind, London seemed to me horrible. I could not eat; I could not sleep; I could only walk over the “stony-hearted streets” and offer my manuscripts to publisher after publisher, who unanimously declined them.”

Source: Pocketmags

Death visited Charlotte again only one year later when cancer took her mother. It was in this year (1856) when Charlotte published her first novel under the pseudonym R.V. Sparling, Zuriel’s Grandchild. Her writing skills were already highly developed at this point and her capacity for the sentimental and melancholy gothic was beginning to blossom, as a popular passage demonstrates: “Oh! there is a ceaselessly returning spring for everything save the human heart; the flowers of the garden bloom and fade, bloom and fade season after season, while the hopes of our youth live but for a brief space, then die forever”.

1857 brought the publication of her second novel, The Ruling Passion under the name Rainey Hawthorne, and a marriage. Charlotte Riddell married civil engineer Joseph Hadley Riddell, and although the pair did appear to be happy by all accounts, Joseph’s terrible head for business and a constant string of bad investments meant Charlotte became the main earner of the Riddell household, often having to keep to strict publishing deadlines to pay off her husband’s debts in time. Her third novel, The Moors and the Fens, was published in 1858 under the name F. G. Trafford and brought the couple enough money to keep them afloat for a time, but Joseph’s ill-advised business investments meant Charlotte did not see the profits of her work for long.

Charlotte Riddell used the pseudonym F. G. Trafford until 1864. Her decision to publish under her name, Mrs J. H. Riddell, came after she left her publisher Charles Skeet, whose terms she grew increasingly dissatisfied with, and signed a new contract with the Tinsley Brothers. William and Edward Tinsley were known in London for publishing sensation novels – literary works that Matthew Sweet of the British Library explains “play on the nerves and thrill the senses” – which Charlotte Riddell must have felt fit her writing.

Novelist of the City & Magazine Work

While Charlotte and Joseph suffered from their fair share of marital problems, Joseph’s knowledge and experience of London’s financial district, or ‘the City’ has it was known to Londoners, became a key part of her writing career. Through her husband, Charlotte learned about business dealings, loans, debt, finance and court battles, and she incorporated these into her work, notably in her most successful novel George Geith of Fen Court (1864). This tale follows a cleric who abandons his religious way of life to become an accountant in the City. It was so successful that it went through several editions and theatre adaptations, and earned Charlotte a loyal and open-minded reading community thereafter.

About the topic, Charlotte said: “you could take no better guide than myself; but alas! many of the old landmarks are now pulled down. All the pathos of the City, the pathos in the lives of struggling men, entered into my soul, and I felt I must write, strongly as my publisher objected to my choice of subject, which he said was one no woman could handle well.”

It was in the 1860s that Charlotte got involved with magazine work. She became part-owner and editor of St. James’s Magazine, one of the most prominent literary journals in London which were established in 1861 by Mrs S. C. Hall (pen name of Anna Maria Hall); she edited Home, and she wrote story stories for the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge and Routledge’s Christmas annuals.

Charlotte also produced some semi-autobiographical work during this period, including A Struggle for Fame (1888) which explored her difficulties in becoming a successful writer, and Berna Boyle (1882) about her native Ireland. Also, she published an indulgent sensation novel, Above Suspicion (1876), which was said to be on par with Mary Elizabeth Braddon, the most popular sensation novelist of the time.

Source: WalesOnline

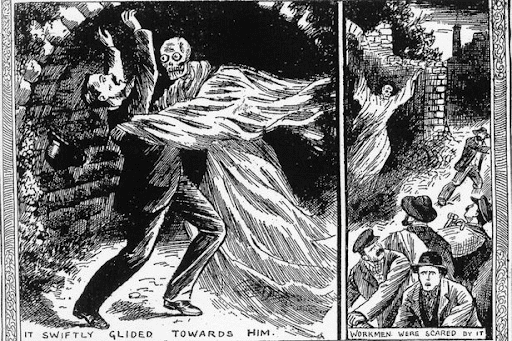

Victorian Ghost Stories: Tales of the Supernatural

Charlotte’s most memorable works are her supernatural stories, with literary critic James L. Campbell going as far as to state that: “next to Le Fanu, Riddell is the best writer of supernatural tales in the Victorian era”. Charlotte Riddell wrote dozens of short stories about ghosts and wrote four novels with supernatural themes: Fairy Water (1873), The Uninhabited House (1874), The Haunted River (1877), and The Disappearance of Mr Jeremiah Redworth (1878) (although these were rarely reprinted and are now widely considered to be mostly lost).

The Victorian era was rife with ghost stories and tales of the supernatural. This is, at first glance, arguably a strange phenomenon given that the Victorians were, as Professor Ruth Robbins states, “a really technologically advanced, scientific and rational people”.

So why were the Victorians so fascinated with them? In its simplest and most general understanding, it comes down to a combination of religion and scientific advancement.

Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1859) and The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (1871) brought evolution theory to the forefront of modern scientific thought. Although Christian himself, Darwin’s work suggested that the omnipotent God upon whom life was dedicated to may not be real, or if he is real, he does not have as great an impact on life as previously thought. Darwin’s work essentially placed humanity on par with animals, shattering the Victorian belief that they were central to the universe. As a result, many began to fiercely cling to religion, particularly aspects of Catholicism. Unlike Protestantism, which did not adhere to what they saw as religious theatricality as they believe spirts immediately go to either Heaven or Hell, Catholicism not only believed in ghosts but taught its congregations that those stuck in purgatory, the in-between place of suffering before one goes to Heaven or Hell, can revisit the living and wreak havoc on their lives.

Scientific advancement and economic changes were also a contributing factor. Kira Cochrane, a Guardian journalist, explains: “The popularity of ghost stories was strongly related to economic changes. The industrial revolution had led people to migrate from rural villages into towns and cities and created a new middle class. They moved into houses that often had servants, says Clarke, many taken on around October or November, when the nights were drawing in early – and new staff found themselves “in a completely foreign house, seeing things everywhere, jumping at every creak”. Robbins says servants were “expected to be seen and not heard – actually, probably not even seen, to be honest. If you go to a stately home like Harewood House, you see the concealed doorways and servant’s corridors. You would have people popping in and out without you knowing they were there, which could be quite a freaky experience. You’ve got these ghostly figures who inhabit the house.”

“Lighting was often provided by gas lamps, which have also been implicated in the rise of the ghost story; the carbon monoxide they emitted could provoke hallucinations. And there was a preponderance of people encountering ghosts in their daily life come the middle of the century. In 1848, the young Fox sisters of New York heard a series of tappings, a spirit communicating with them through code, and their story spread quickly. The vogue for spiritualism was underway. Spiritualists believed spirits residing in the afterlife were potentially able to commune with the living, and they set up seances to enable this.”

So, ironically, ghosts and tales the supernatural seemed to be encouraged by modern scientific inventions and thought as opposed to being driven out by them.

Charlotte Riddell tapped into this consciousness with ease, creating beautiful and haunting tales of lost loved ones returning from beyond the grave. Her most famous surviving works three collections composed of short stories she regularly published in various anthologies and magazines: Weird Stories (1884), Idle Tales (1888), and The Banshee’s Warning (1894).

Charlotte’s Later Years

Charlotte’s husband Joseph passed away in 1880, leaving a substantial debt behind him. Although Charlotte was able to eventually pay these debts off because of her successful writing career, it became increasingly difficult as the years went on because the ghost story fell out of fashion.

Unconventionally, after her husband’s passing Charlotte found a long-term companion in Arthur Hamilton Norway. Charlotte was fifty-one at the time and Norway was several years young so this would likely have sparked gossip and rumours amongst Victorian socialites. They travelled together, mostly to Ireland and Germany, before breaking off their companionship in 1889. It is unclear as to whether this was an intimate, sexual relationship or just a close friendship.

The 1890s provided particularly difficult for Charlotte because her work was not as popular as it once was, and she lacked a male companion with whom to share her financial burdens. In 1901, she became the first writer to win a pension from the Society of Authors – £60, which is the equivalent to around £4,5000 in 2020 – but it did little to relieve her spirt.

Charlotte Riddell died at 73 on 24th September 1906 from cancer. Her work remains some of the most popular and influential of the Victorian era.

She is buried in St. Leonard’s Churchyard, Heston.